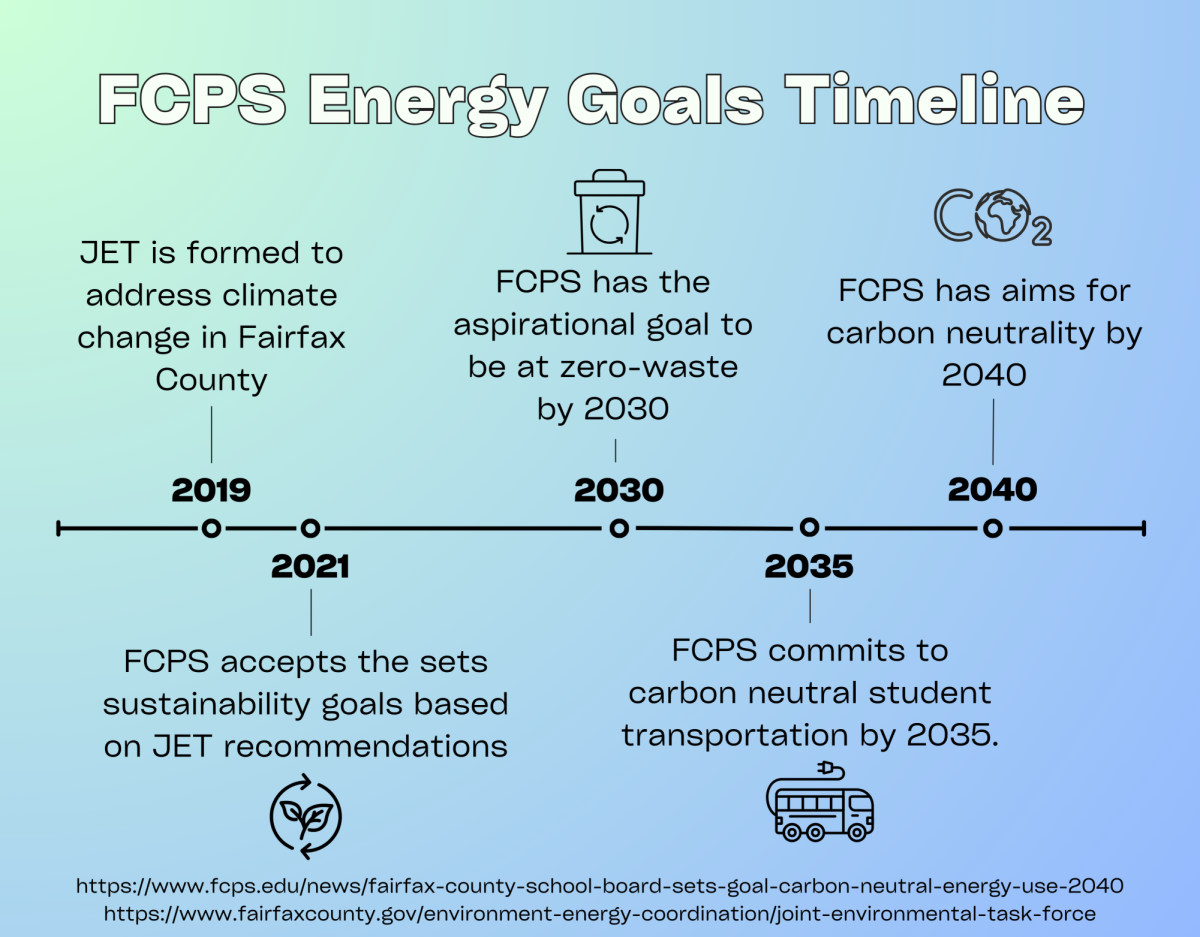

“Cheerleading is All I’ve Ever Known:” The People Behind the Pompoms

Amy Steward

Cheerleaders performing for the student section during a home varsity football game this fall. Often some of the first to arrive and last to leave, the cheer team typically spends every hour from the end of school to midnight on football Fridays practicing, setting up, performing, and traveling.

February 8, 2023

After a long day of school, the empty hallways still echo with the voices of cheerleaders practicing their chants. JV is outside, covered in paint from making posters, and varsity is practicing their pyramid yet again, perfecting it before this week’s pep rally.

This is just one moment in the hectic life of a cheerleader — most of their time is spent outside of performance, whether at practice or out serving the community as a team. Football games, while the most public, are the least amount of work. Cheerleaders must live up to the expectations of coaches, teachers, students, and the community.

“Yes, we are at the games cheering, waving our poms and whatnot,” said junior Layla Garber, a member of varsity cheer. “But there are other skills and other talents within cheer, like stunting. It does take a lot of strength to do what we do. And tumbling, that just takes practice and time to get the skills we have.”

Coaches expect commitment, peers expect positivity, and spectators expect perfection. In short — cheer is much more than just shaking pompoms on the sidelines.

Our coaches expect “us to have a positive attitude,” said varsity cheerleader junior Anna Kate Hankins. “Like having a smile on your face every day and just being a nice person.”

Because cheer tends to be a high-profile sport — appearing at everything from football games to send-offs to school events — its members are expected to be cheerful and exuberant.

“I expect a lot from my cheerleaders,” said former head cheer coach Denise Stripling. “I expect them to help other people get spirited or try to have a good day, and try to just be a good ambassador to our school — to make our school look like we are really a good place and that we want to be here, and that people want to come here.”

The emphasis on image and positivity means that the physicality of the sport isn’t always obvious; according to the National Library of Medicine, 83% of cheer injuries occur during practice away from the public eye.

“Depending on the practice the day before, you wake up sore; like right now I am sore,” said Garber. “Then you do the whole school day, and then you go to practice. You change and roll out mats, stretch, warm up, and then do whatever the coach says.”

However, before members can participate in all these practices and performances, prospective cheerleaders must first submit to a lengthy and rigorous tryout process. This includes three clinic days — two practice days and a mock tryout — before the official tryout.

“It was really nerve-racking,” said Hankins about the process. “It was a whole lot different because I just moved here. I would say I put higher expectations on myself to make the cheer team since I was new as a sophomore.”

Joining high school cheer is rarely a spur-of-the-moment decision; for most cheerleaders, it’s been a part of their life for a very long time. Senior varsity cheerleader Kennedy Holcomb, for example, is the daughter of a former Dallas Cowboys cheerleader; she started cheer at four years old and has been doing a variation of the sport for the past 13 years.

“Cheerleading has always run in the family, so it is kind of all I have ever known,” said Holcomb. “My mom was a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader. She inspired me to become a cheerleader. I have cheered since I was five, and I have loved it ever since. I also hope to one day become a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader just like her.”

Being a cheerleader is also a major time commitment. On average, a varsity cheerleader at Champion will spend about twelve hours a week practicing or volunteering, plus four hours minimum performing at a football game. Holcomb, for example, had to cancel a family Disney trip because it conflicted with a football game. This expectation doesn’t stop at the team members, either — coaches, boosters, and parents also feel the pressure.

“I am here everyday from 7 a.m. until probably 7:30 p.m. or 8 p.m. [It’s] one of the hardest jobs I have ever done,” said Coach Stripling.

While cheerleading demands a lot of its participants, there are still dozens of people that try out every year. This is because time and again members say it gives a chance to connect to the community, school, and the family it creates — there’s a sense of friendship, community, and connection that is rarely found outside of the team dynamic.

”People look at cheer as if it is not really a sport, but we go out there, and run, and we go out and stretch, and we tumble, and we do high kicks, and we do jumps,” said Coach Stripling. “So I have always frowned upon the fact that people don’t think cheerleaders are athletes, because we have a talented group of girls that can do all kinds of things.”

This story was originally published on Charger Ink on February 3, 2023.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)