Disclaimer: Moore Public Schools condemns racism and is committed to creating an inclusive school environment for all. MPS believes meaningful discussions are imperative.

MOORE, OKLA. – Classrooms in the United States are changing as the transition from chalkboards to smart boards continues. However, has much really changed for students of color, particularly black students, in public schooling?

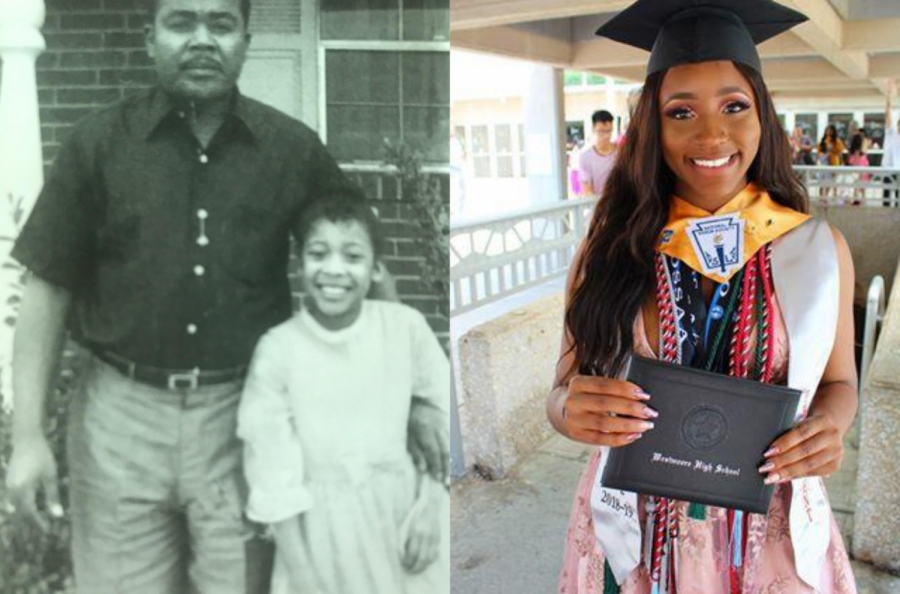

Here’s what schools looked like in Oklahoma from the 1970’s and from the present.

PART I. Recalling prejudice from her public school days in the 70s, Brenda Palmer tells a story about her third-grade teacher and more.

Disclaimer: Given the sensitivity of this article, names of secondary subjects will be protected.

In a phone call with a student, Brenda Palmer, a Westmoore High School special education teacher, was asked “what was it like being a black student in the 70s?” She paused. Seconds later she answered with a few words:

Very difficult. Isolating. Microaggressive.

Growing up in her red and white brick home near the cul-de-sacs of Mid-Del City, a predominantly white area at the time, Mrs. Palmer quickly learned she was different. She now looks back on her memories of elementary school, particularly Ms. Autumn’s third grade class at East Oak Elementary.

Like all of Palmer’s teachers, Ms. Autumn was a middle-aged, full-figured white woman. She adorned herself in rose-pattern dresses and fragrances. With curly, brunette hair, Autumn took pride in her well-manicured nails.

She never said anything ugly or rude to Palmer, yet there was a sense of disgust and hate present. Ms. Autumn was like a kind mother to her students— all expect Palmer. She would smooth kids’ bangs out of their eyes and touch them in such affection that Palmer never received.

“Ms. Autumn was extremely kind to all the other students but uncomfortable with interacting with me. When I was in her class I didn’t understand why, but I continued to pursue her attention by drawing her pictures and attempting to be the model student. Each evening I remember wondering if something was wrong with me. Was I dirty? Did I smell bad? Was I not smart enough?” Palmer said.

Ms. Autumn passed out graham crackers and apple juice for her students everyday. Palmer quickly noticed a pattern. She never had a full cracker and was always last to receive snacks— often times after her peers helped themselves to seconds. Autumn, every afternoon, would unkindly dump juice in Palmer’s paper cup, like she did not want Palmer to enjoy it. Like she was disgusted to be even serving Palmer.

“While we were in class, she always gave me the demeaning jobs. Other kids got to erase the chalkboard and were the line leaders. My job never changed. I always emptied the trash. It was always the domestic jobs,” Palmer said.

Ms. Autumn’s rejection began to disturb Palmer’s eating and sleeping patterns until a meeting with her parents and the principal. Afterwards, Autumn began to force smiles at Palmer and be kind to her in class. She even offered compassion when Palmer was stung by a red ant on the playground during recess. However, to this day, Palmer’s stomach would turn at the taste of graham crackers and juice.

“My peers even noticed. Steven mentioned it to her in front of the entire class. He exclaimed, ‘Look, Brenda isn’t getting the crumbs any longer!'” Palmer said.

***

Around the time Palmer was in the fifth grade, Oklahoma schools integrated and implemented the “Finger Plan,” which bused black students to white schools (and vice versa). She lived in a white neighborhood that was bused to Crescent Hills Fifth-Year Center, on the northeast side of town.

I lived that. I lived being judged and not being included. I know what that feels like and I never want to be responsible for excluding anybody or making anyone feel that way. I just want to love all people

— Mrs. Brenda Palmer

Because of her skin tone and her times living in a white community, she faced difficulty fitting in and endured insensitives from both white and black people, who taunted the way she spoke. She even tried to learn how to talk ebonically to fit in.

“I was not black enough, but I was, also, not white so I was kinda in the middle. It was isolating. I was often called an oreo because I lived in a white neighborhood. It was taunting until I finally decided to be myself. If people liked me, they liked me for me. If they didn’t, shame on them,” Palmer said, laughing.

As she continued her education, Palmer found her identity. She found a group of friends amongst white and black juniors and seniors that she still keeps in touch with today. Years later, she obtained a degree and found the love of her life. After homeschooling her children, she was strategic in including Black History that most schools did not teach in much depth. In addition, she taught her children Christian values and principles she and Mr. Palmer wanted instilled in them.

Last year she was also a Moore Public Schools district finalist for Teacher of the Year. She currently resides in room 107 where she is today.

PART II: WHS alumnus and former STUCO President Joy Okpoko relives racism at Westmoore.

Joy Okpoko needs no introduction. She did it all during her time at Westmoore. She was a national finalist in Original Oratory in her three years of speech and debate. She served as Westmoore’s first female black student council president and was also named Miss WHS at Prom 2019 by her peers, in addition to participating six plus clubs and organizations.

From the outside looking in, she was a well-put together, iconic queen. While she was still indeed those things, she also felt from the pressure and racial mistreatment.

From pre-k to twelfth grade, Okpoko attended Moore Public Schools. At Westmoore, she found her confidence and life-long friends. But looking back on the memories, she relives the pain of racism, wishing she had enough strength to defend not only herself, but other black students.

Her transition to high school in freshman year was difficult and, at times, lonely. However, she began to find her voice when she became a student council officer in her sophomore year. Her confidence only grew when she was crowned Speech and Debate State Champion that same year.

Even with all of those accomplishments, she always felt like she was constantly trying to prove her worth. Without her credentials and achievements, she feared she would not be listened to or respected.

“It was almost as if I was anything less than an extraordinary black female student, I wouldn’t be respected or listened to. I made the most of my time at Westmoore and had fun while doing so, but now being outside of it, reflecting on my experience, I can now more clearly identify how hard it was to feel seen,” Okpoko said.

From her experience, racism existed at Westmoore in the form of microaggressions— everyday slights, put downs and insults towards minorities. Okpoko saw this, in one common example, in how people spoke about black girls. Passive-aggressive comments like “you’re so pretty for a black girl” and “you’re the only black girl I like” were said to her.

“This holds black students to an unreasonably higher standard, applauding them for being ‘one of the good ones.’ Unfortunately, that is something black children, myself included, were exposed to very early in life, inside and outside of school, so I eventually became numb to subtly racist remarks from my peers,” Okpoko said.

Down the line, she felt put down unjustly and overly criticized by teachers, administrators, and sponsors. It frustrated her to do just as much, if not more than, her non-POC peers and be scorned for every mistake she made— all while some of her non-POC counterparts would knowingly behave inappropriately because they knew their proximity to authority figures would save them from any real trouble.

Within the classroom, Okpoko witnessed teachers yell at black classmates over minuscule misunderstandings while simultaneously allowing white counterparts to disrupt instruction time and leaving class frequently.

“I have a million experiences like that at Westmoore, but how does one report that? I believe the underlying racism in those situations is not enough in the eyes of administrators to deem as racist and wrong,” Okpoko said.

Today, Okpoko currently attends the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, studying business economics with a concentration in management. These past months have forced her to confront and heal the wounds racism has put on her.

“Black students have years and years of pain and trauma behind the color of their skin. The world has finally taken notice of that pain, but it has been happening in silence our whole lives. Listen to and believe in black students. To non-POC readers, have uncomfortable conversations and I mean really have them. I pray Westmoore, and MPS in general, begins to hire teachers and administrators who value all students equally and removes any who are not willing to listen, take accountability and learn,” Okpoko said.

As she continues her Ivy League studies on the East Coast, 1400 miles away, Okpoko has faith in district leadership and the power of black voices because “once a Jaguar, always a Jaguar.”

“Moving forward, I cannot and will not tolerate any racist speech or actions inflicted on me or others. No black student should have to be the president of six organizations to be valued. I hope I can empower other students of all races to do the same,” Okpoko said.

PART III. Black and other BIPOC students acknowledge the progress that has been made but also draw attention to what needs to be done.

Due to the sensitivity of this article, in order to protect the identities of students involved, the names of Grey’s Anatomy characters will be used as pseudonyms in place of students’ names.

I don’t think Westmoore is entirely racist. I think there are just bad apples on a good tree. I totally have friends who aren’t black who support me in all endeavors

— WHS Unnamed Junior

A couple weeks ago, 128 MPS secondary students and alumni were surveyed in regards to racial issues at school. 78 participants reported racial discrimination, prejudice, or hate at school. When asked by who, 51% of those participants indicated it was by their classmates while 37% indicated it was by BOTH their classmates and faculty. Even though the sample size of the survey was small in comparison to Moore’s 7000+ high schoolers, it gives insight into students’ experiences.

“Minority students already have to fight and struggle to be treated equally in many areas in life, and school should not be one of those areas,” senior Jo K. said.

“Being black in America racism is inevitable. Over the years you learn how to identify if people are ignorant or intentionally trying to be racist. I would say there are a lot of good people here at Westmoore who want to understand, however there are still people here that would rather remain ignorant to the problems that Black people face today. Teachers, coaches, administrators are no exception. How can you talk to the people who are here to help you with your problems when they are the problem,” senior Mark S. said.

In the same survey, all participants claimed that they have heard a non-black classmate say the “n-word.” However, not many students openly speak about this.

“I have heard the n-word come out of many students’ mouths. No one should be saying the word anyway, especially non-black students,” junior Miranda B. said.

Many minority students feel as if racism is being normalized to which they do not even realize how toxic a moment is until it is over. Although explicit racism is not really something kids today have to worry about, as Okpoko said, students feel uneasy by microaggressions and subtle jabs at their race.

“The worst part is that covert racism has become such a staple that black kids at school have internalized and become anti-black as well: giving out n-word passes and allowing their friends to say ‘my friend is black’ because it is honestly the easiest thing to do,” senior Arizona R. said.

Hearing about the struggles of minorities and statistics associated with it is heartbreaking. They paint Westmoore to be a hateful, racist school. While that survey has some truths, it does not accurately portray the true supportive nature of Westmoore.

“I don’t think Westmoore is entirely racist. I think there are just bad apples on a good tree. I totally have friends who aren’t black who support me in all endeavors,” junior George O.M. said.

The reality is not every white teacher and student is racist. White people additionally are not the only ones who say insensitive things. People from all races and backgrounds can be racist, though not many would like to admit it. Coherently, people from different ethnicities can be allies.

Looking around them, students see friends of diverse backgrounds and teachers who genuinely care for them.

“In my experience, there are many teachers that care for me and that have my back during times of need. Regardless of race, I would stand up for any classmate that is in trouble,” junior Addison M. said.

“I feel as though I have a diverse friend group that doesn’t care about race and will support me full heartedly. I connected with teachers in elementary school,” freshman Derek S. said.

Students with bad teacher experiences may be hesitant to trust staff. However, teachers, counselors, and administrators have pledged to respect and listen to the challenges black and minority students face.

“I want everyone in my classroom to be comfortable, because they can’t learn if they are uncomfortable. I do believe that black lives matter, and I don’t think that statement should be controversial. I don’t believe that human suffering is political. When my students tell me something is hurting them, especially if it is something I am doing, I try to stop what is hurting them. This year, that looks like inclusive literature choices in my classroom,” honors English teacher Mrs. Michaela Gillmore said.

Whether it is more accountability for racism within classrooms or more diverse staff, MPS administrators have been listening and having conversations with their black students and faculty.

“I grew up in Moore. I love Moore. Moore has always been home. That is why I feel I can say that we can do better with how we interact with black students. I don’t want black students to feel as if they are on an island stranded by themselves when they are in a classroom. I believe in the leadership that is in place in our district. I feel as if our Superintendent and the rest of the administration will do what needs to be done to make sure that black students and students of color are safe from having to experience racism and discrimination,” Mr. Durrell Carter of Highland West Junior High said.

On June 8, the Moore Public Schools Board of Education adopted a “Resolution Condemning Racism and Affirming the District’s Commitment to an Inclusive School Environment for All.”

In addition, curriculum coordinators and administrators are looking into teacher sensitivity training and recruitment of mental health facilitators, a few items on the list of “wants/ changes” by Moore students and faculty.

While there still is a long, rough path ahead, a hopeful future of change awaits the Moore community.

This story was originally published on JagWire on September 3, 2020.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)