First African-American valedictorian Williams aspires to inspire

Courtesy of Elaine Williams

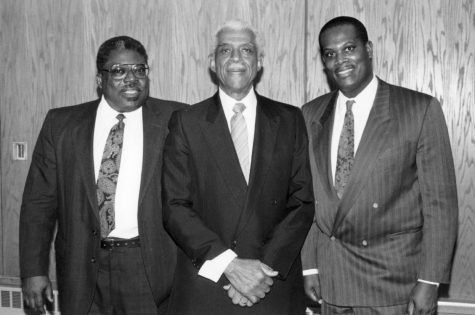

Neil Williams speaks at the ceremony for his promotion to Nathaniel R. Jones Professor of Law at Loyola University Chicago’s School of Law in 2009. Having taught at Loyola for thirty years at the time of his promotion, Williams is the inaugural recipient of the title. The accolade’s namesake, the Honorable Nathaniel R. Jones served as a judge on the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and as general counsel of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

October 1, 2020

Now a professor at Loyola University-Chicago Law School, Grady’s first black valedictorian Neil Williams has come a long way from a shy teenager, who was told by friends that he would never stack up intellectually with white peers.

Williams’ family moved to Atlanta from Gainesville, Florida in the early 1960s. He still remembers the “tail-end days” of Jim Crow.

“I remember the segregated water fountains,” Williams said. “I remember having to go into the sides of buildings instead of the front, even though Brown versus Board of Education had been issued in 1954.”

HIGH SCHOOL YEARS

The first integrated school Williams attended was Grady, which had been integrated in 1961.

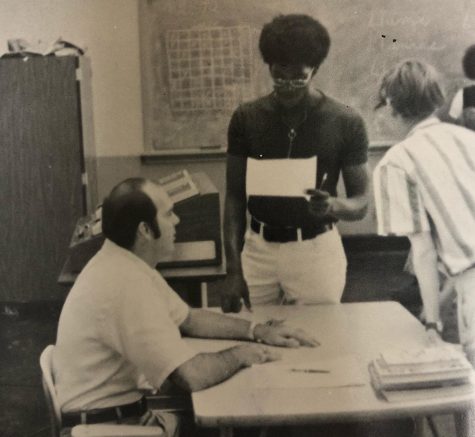

“There were certainly African Americans at Grady before I started as an eighth-grader back in the fall of 1969, but I believe my class and the immediate ones preceding it were really the sources of the significant complement of African Americans,” said Williams, who graduated in the Class of 1974 with a perfect 4.0 GPA.

During Williams’ time at Grady, he encountered significant segregation in the classroom. Williams explained that African-American students were assigned to the print shop for class, where their tasks included sorting printing tools and operating printing machinery, which he believes put students in danger. White students took mechanical drafting.

“When printing work was done in those days, there was this huge clamp that came down, and if you didn’t get your hands out of the way of it quickly, there could be significant injuries,” Williams said. “On the other hand, all of the students streaming in from white schools were put into mechanical drafting, preparing them for careers in science and engineering and so forth.”

Williams originally took on-level classes and was balked at by administrators when he requested honors classes since he had already learned the on-level material in summer courses. It took a white teacher, who recognized Williams’ brilliance in his summer course at Grady, demanding that he be put in honors courses for his wish to be granted.

However, Willaims found more integration in athletics, specifically football and track.

“The [football] coach really emphasized teamwork,” Williams said. “Black and white players got to get along very well.”

While on the football team, Williams found his lifelong best friend in teammate Randy Reed. Reed went on to coach girls track and football and teach math at Grady from 1988 to 2004; he passed away in Jan. 2014.

“My father would describe him [Williams] as the ‘smartest man that he’s ever known,’” Randy Reed Jr., who refers to Williams as “uncle,” said.

Greg Sheats, Williams’s friend and football teammate, felt that Williams provided a positive inspiration to his teammates in terms of his dedication.

“Neil was the type of player that, let’s say, wasn’t necessarily gifted but worked harder than other people that may have been gifted,” Sheats said. “And so, he was looked at as being extremely tough and a hard worker, for sure.”

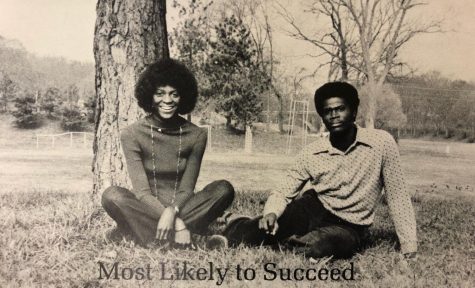

Williams’s motivation to become valedictorian stemmed from an intent on breaking down barriers and to “prove that black people were just as smart and just as capable of achieving these things as whites.”

“I was quite aware of the barriers standing in front of me, in that it was groundbreaking,” Williams said. “And I was intent on doing my best.”

Williams’s valedictory speech, however, didn’t remark on the significance of the feat, which he now wishes it did, although he admits his youthfulness may have played a factor.

“When I did it, I was aware it was an achievement, but I was only 17 and really didn’t have a solid sense of the historical significance overall,” Williams said.

Even though he may have not realized their historical significance at the time, through his family, Williams had connections with civil rights leaders. Yolanda King was in his older brother’s class at Grady. His father, one of the first licensed black veterinarians in the state of Georgia, had an Edgewood Avenue clinic whose patients included Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dog. After Dr. King was assassinated in 1968, Williams’s parents marched in his funeral parade, and his father issued the health certificate for the mules pulling Dr. King’s coffin.

“When Dr. King was assassinated, he was certainly mourned, and we spoke about it in the black community,” Williams said. “But, there was no real sense that what he said and what he did would be recognized the way it is now worldwide.”

PURSUIT OF HIGHER EDUCATION

Williams’s parents were both educated, his father a veterinarian and his mother a school teacher with a master’s degree, and they held the expectation that their four sons would pursue higher education.

Having garnered acceptances to top schools such as Harvard and Yale, Williams attended Duke University as an Angier B. Duke scholar. After taking a semester off due to a near-death experience with heatstroke at the Peachtree Road Race, he graduated in 1979 with bachelor’s degrees in English and management sciences.

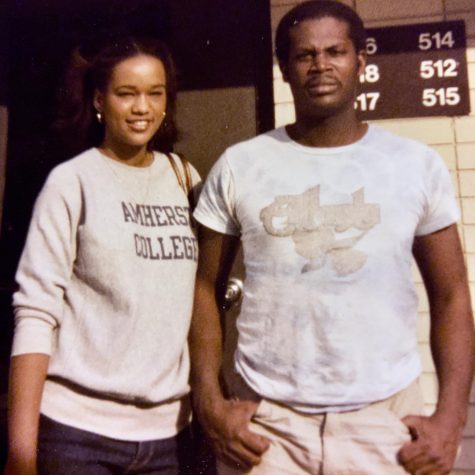

Rather than attending graduate school for English, Williams pursued law, which he was “fascinated by.” He received a Meacham Scholarship to the University of Chicago Law School. Williams met his wife Elaine there in his second year when she was a first-year student.

“When I met him, he didn’t say a word. He didn’t talk at all,” Elaine Williams said. “He was just genuinely one of the quietest people I’ve ever met in my life…I engaged him in conversation, and he was really sweet and very warm, but still shy, and very quiet.”

Elaine broke Williams out of his shell by offering to give him rides to his apartment in exchange for him buying her lunch. They started spending more time together studying and eating and quickly became best friends.

“We studied a lot of times and we ate dinner,” she said. “So literally my husband fed me all of my first and second years of law school.”

Williams wrote love poems for Elaine, but at first, she was reluctant to date him because of their close friendship.

“Every single day, he wrote a poem — poem could be one sentence. He had a little book; it’d be one sentence, and he’d just leave it there open,” Elaine said. “It might just be one sentence, or it might be a page and a half, depending on what his mood was.”

The poems spanned an entire year, Elaine’s second, and Williams’s third year at the law school.

“So, how do you not fall in love with somebody that would write you a poem a day for the year and feed you lunch and dinner every day?” she said.

The two married in 1984 after they had both graduated from law school.

EARLY LAW CAREER

Following commencement, Williams had a federal district court clerkship for two years with Judge George Leighton, who was appointed as a U.S. Circuit Court judge by President Gerald Ford and was also a past president of the Chicago chapter of the NAACP. When he was a lawyer, Leighton represented a black couple who were being harassed by whites for purchasing a home in a majority-white suburb of Chicago. Leighton was charged with inciting a riot and was represented by eventual U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.

While Williams was clerking for Judge Leighton, Leighton presided over a copyright lawsuit against Australian pop group the Bee Gees, in which a Chicago man accused them of plagiarizing their 1977 hit “How Deep Is Your Love,” from “The Saturday Night Fever,” soundtrack. The jury reached a guilty verdict.

“I still remember, when that verdict came out, one of the Bee Gees crying out [mimics Australian accent], ‘The verdict is a lie! The verdict is a lie!’” Williams said.

Judge Leighton overturned the jury’s verdict based on a lack of evidence of the Bee Gees having access to the plaintiff’s song.

After his clerkship, Williams worked for a prominent Chicago law firm. While there, Williams experienced racism from his colleagues. A head partner in his group failed to invite only him to a corporate law holiday party. Another partner called his black colleague the N-word; the same partner exclaimed that the pianist at a party “play some boogie” for Williams and Elaine.

“I sensed that a lot of whites in the group of the firm didn’t welcome my presence,” Williams said. “Several incidents at the law firm, in particular, are among the most unsettling and discomforting episodes of overt racism that I’ve encountered in my life. In the interest of balance, however, it is always important to take into the totality of the circumstances in reflecting upon one’s life experiences. And, I would be remiss not to point out that there were also people at the firm who went out of their way to be nice to me.”

Joe Ehrman, a senior partner at the law firm, served as a steadfast mentor to Williams. Ehrman gave him honest feedback, which was “very difficult to come by,” Williams said.

Williams emphasized the value of a mentor that may not have the same political leanings as their mentee.

“People can be great with you one-on-one and have different political leanings,” Williams said. “If someone is honest and really cares about you one-on-one, those are the greatest mentorship opportunities you’ll ever have, so be sure to take advantage of them.”

Elaine, who was working at a different law firm at the time, felt that, although Williams was excelling professionally at the firm, he needed to embark on a more fulfilling career path. She reached this revelation after watching Williams embark on his commute to work hunched-over with one foot on the sidewalk and the other in the dug-out rudder.

“It was like he was walking with one foot,” Elaine said. “He was up, down, up, down. It was so sad.”

She knew that Williams had dreams of becoming a law professor and was able to arrange an interview for him at Loyola University Chicago Law School through a colleague. Williams was hired as a professor and started teaching contract law in the fall of 1989.

Williams still worked at his law firm the summer before he started teaching. During that summer, the firm held its summer associates program. One of the program’s recruits was a highly sought-after Harvard Law School student: Barack Obama.

When Obama arrived at the firm to meet his assigned mentor, Williams was the one to introduce them, as he had met Obama for lunch on an earlier date.

“I was there the first moment Barack Obama laid eyes on Michelle Robinson, and I’m the one who got to say, ‘Michelle Robinson, this is Barack Obama,’” Williams said. “If there’s such a thing as love at first sight, this was it. His eyes lit up like stars. I could see he was immediately smitten.”

When Obama spoke at Loyola Law School on Jan. 20, 1999, on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Williams introduced him. Exactly a decade later, Williams witnessed Obama’s inauguration.

PROFESSORSHIP

When Williams first started teaching at Loyola, Elaine feared that his shy temperament would impair his ability to teach a class. She ended up sneaking into one of his first classes, hiding behind a pillar and shh-ing any students that noticed her; her fears were immediately assuaged.

“I stood there, and my husband was walking side to side,” Elaine said. “He had one hand in one of his pockets, and he was like Michael Jackson on stage.”

Sari Mondry, a former student of Williams who now works as his research assistant, said Williams is known to often bang on the podium and “squeal” in excitement, creating a “warm, inviting room.”

“He’s always literally a firework,” Mondry said. “You can’t be sad or just not laugh. If you don’t love him, something’s wrong with you as a human.”

Norman C. Amaker, who was also a professor at Loyola Law School at the time, served as Williams’ mentor. Amaker served as a staff attorney for the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund in the early 1960s and served as counsel for plaintiffs in many civil rights cases. One of his notable clients was Dr. King, for whom Amaker sneaked the first draft of Letter from a Birmingham Jail past prison officials.

“He [Amaker] gave me some of that perspective I had perhaps been missing about the history behind all the things that led up to the accomplishments of the civil rights movement,” Williams said. “It was transformative.”

Amaker passed in 2000. In 2002, Williams was the inaugural recipient of Loyola University Chicago School of Law’s Norman C. Amaker Award of Excellence.

In order to “carry on his [Amaker’s] spirit,” Williams serves as president of the Midwestern People of Color Legal Scholarship, where a group of law professors of color shares their perspectives on history and law and their implications in regard to race.

In 2009, Williams was named the inaugural Nathaniel R. Jones Professor of Law. The professorship honors the Honorable Nathaniel R. Jones, who served as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and as general counsel of the NAACP. The award marked Williams’ third decade teaching at Loyola.

Former student Mike Flanagan praises Williams for his devotion to students and especially for his role as an advisor to the Black Law Students Association.

Williams “allowed us to have some comfort in knowing that there was somebody in the administration that really cared about us and gave us a sense of power and empowerment,” Flanagan said.

Steve Ramirez, also a professor at Loyola Law School, has co-authored two pieces with Williams, both dealing with the nation’s democratic history as it relates to race. He describes the stark contrast in their formative environments as a crucial dynamic when they authored the pieces.

“Between the two of us, we’ve seen a lot, right. So, Neil can explain what it was like to grow up in Jim Crow South; I can’t explain that,” Ramirez said. “I could explain the privilege of the North Shore of Chicago — what that’s worth … We make a great team.”

Caroline Shoenberger, a friend of Williams’s, would invite him annually to speak for her business law course at Harold Washington College in Chicago. She lists him as her number one guest speaker, inspiring students to apply to law school because of his compelling lectures.

“I didn’t have to tell them to put away their cell phones. They were mesmerized,” Shoenberger said. “He not only mentored me, he basically inspired my students.”

Shoenberger describes Williams as “someone who believes in the rule of law and wants to share his love of the law with others.”

Williams has been known to take hours out of his day to explain concepts to students.

“Professor Williams took time, he set aside a day where he literally just made himself available to the entire class section to ask questions, and that man stayed there until the last person left, which I understand was sometimes close to midnight, just answering questions for that exam,” said Williams’s former student and contract law teacher’s assistant Jechonias James.

Now teaching his students virtually during the pandemic, Williams still keeps his same “firework” energy and commitment to them. Elaine describes her joy in hearing her husband teach from upstairs.

“It tickles me! It’s a delight to hear,” Elaine said. “I can hear him singing. Singing!”

Williams describes the 31 years he has spent working with young people, seeing them develop and do great things as “the most fulfilling thing I have ever done.”

Elaine is thankful that the “shyest, most quiet person” she met at the University of Chicago has found his passion in teaching, and she said his Grady roots are essential to where he is now.

“He was a product of Grady,” Elaine said. ”His mom was a teacher and all of his aunts were teachers, but part of what framed him and gave him the basis to be able to go to Duke and the University of Chicago and the federal district court clerkship was Grady.”

This story was originally published on The Southerner on October 1, 2020.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)