Busting Bliss: Reversing the Wrongs Done to Native Cultures

It’s all too easy to turn a blind eye to centuries of oppression that have left Native peoples among the poorest and most at-risk in the country.

November 30, 2020

I remember being in Kindergarten and coming into school the day before Thanksgiving when the tables were decorated with construction paper feathers. We would eat a little fake dinner and talk about how the Pilgrims came to America to “be friends” with the “Indians” as we cut out little yellow buckles for our paper hats. We learned about how the Pilgrims brought gifts and modernity.

Nothing wrong with that, right?

It’s hard to blame six year olds for the deeply ingrained ignorance that comes with any colonial talk of native peoples. After all, who were we to correct our teachers on the decades of genocide against the original inhabitants of this land?

But when we consider all of the little ways we white-wash our history, it’s alarming how early it begins, and how many years of ignorance we must dismantle.

As a white person, I’d like to issue a disclaimer: I can’t and won’t speak for Native people. I’ve never experienced the life or discrimination that Native people face, and I never will, and I certainly don’t know the trauma that they have been through.

But shedding our ignorance is something that is much harder to do alone, and for that reason I’d like to share what little I’ve learned.

When we talk about reshaping our ideas and knowledge of a culture, one of the most important things to do is be conscious of the language we use. One cannot be a proponent of the Black Lives Matter movement and still use racial slurs targeted at the Black community, and in that same vein we must reevaluate how we speak about Native people and communities.

In a recent TikTok video, a popular creator who goes by their social media handle, @thegreatchameleonquest, asked Native users of the app what terms they prefer. An overwhelming number of commenters and people who responded using the app’s “duet” feature said that they prefer “Native” or “Indigenous” over “Native American” or “Indian”.

It’s none of my business— nor is it the business of any non-Native person— to question why they prefer one term over the other, but it’s always better to at least attempt to be cognizant of the language one uses when referring to a marginalized group that they aren’t a part of.

But even as many people start to try to be more aware of their relationship with Native people— either as an ally or as someone who knows and interacts with the Native community on a regular basis— it’s become more and more clear just how little respect our society has for the people it oppressed in order to prosper.

Up until July, Washington’s football team went by the name “The Washington Redskins,” with a cartoon image of a Native person as their mascot. Until the team was renamed “The Washington Football Team,” for nearly 88 years, the team used a common slur for Native people as their identifier, with an even more grotesque depiction of a seriously misunderstood culture as their mascot. Even more abhorrent was the team’s refusal to acknowledge the insult.

When we see massive corporations or franchises profiting off of a culture, it’s easy to assume that they employ a large number of people from that culture, or donate to causes surrounding it, but this is often not the case.

What’s even more difficult to comprehend, however, is how easily we put blinders on when seeing white interpretations of Native culture, and not recognizing it as Native at all.

I can admit— although I am embarrassed to say— that for the longest time, truly up until middle school, I didn’t even recognize dream catchers as a part of Native culture. I had one hanging in my room for the longest time, and if I had to bet, I’m pretty sure I bought it at The Dollar Store.

These misrepresentations of Native culture are everywhere, and what’s worse is that sometimes they’re not misrepresentations at all, but stolen traditions, patterns, and items of significant importance to the culture— like dream catchers. Companies like ASOS still profit off of selling traditional Native prints, calling them “tribal,” whereas other companies, such as Nordstrom and Urban Outfitters, just rebrand them as “southwestern.”

But where does all of this leave actual Native communities?

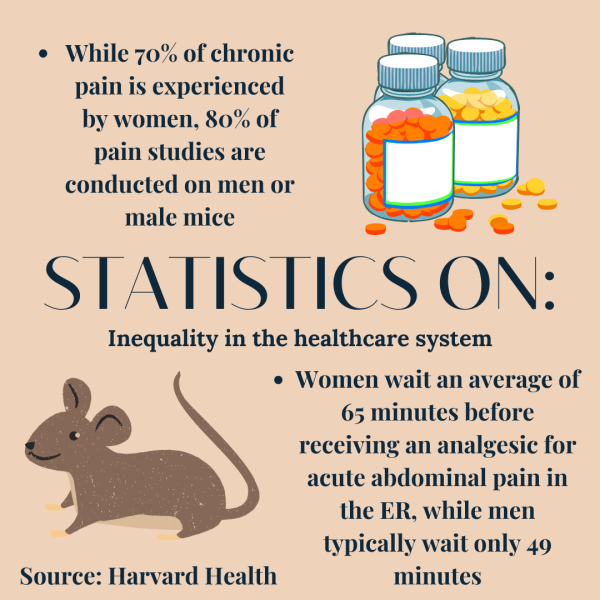

One out of every three Indigenous people lives below the poverty line, with a median income of $23,000 a year. Native families living on reservations are even more impoverished than their counterparts who inhabit other parts of the country.

With all of that corporate culture stealing, you’d think that even a little bit of the revenue would trickle down to Native communities. Unfortunately, this isn’t the case.

What’s even worse is that, even amidst a pandemic, Native communities are still at the bottom of the American hierarchy. Imagine working at a health center— one that specifically cares for your area’s Indigenous population— and as the pandemic hits you request medical supplies for your community, only to be met with a box of body bags. That’s exactly what happened at a Seattle health center for Native Americans earlier this year.

Navajo Nation, as well as several other tribes, were hit harder by COVID than any other group in the country, with Native people three times more likely to contract the virus than white Americans.

COVID deaths are one thing— it’s a tragic, but albeit temporary moment in our history— but the increase in deaths of Indigenous people is yet another trauma to add to the list.

Native American women are ten times more likely to be victims of sexual assault, rape, kidnappings, and murder than any other group of people in the country. Grassroots efforts have drawn more attention to the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women movement over the past few years, but the epidemic has only continued. With very few resources, and a lack of priority placed on the issue by law enforcement, there isn’t even a number of how many cases of missing or murdered Indigenous women have occurred since the start of 2020.

A new partnership between the Department of Justice and the Bureau of Indian Affairs is aiming to improve data management and tracking, but noting the current political climate, Native issues are likely to slip through the cracks.

I am not Native. I’ve never known— and will never know, the heartache that must run rampant through Indigenous communities. I don’t know what it’s like to be Native or fight for Native causes as someone whose life will be affected by the outcome. But what I do know is that there is a lot of learning and unlearning to be done.

What I know about Native culture is just a start, and I hope I can continue to learn and do more to uplift Indigenous communities and their causes. That’s all I am able to do, and I implore you to do the same.

******

Especially with COVID-19 cases rising across the country, here are some Native-owned businesses that you can support as the holiday shopping season commences:

This story was originally published on The Uproar on November 25, 2020.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)