Art Imitates Life

Student artists draw inspiration from politics

Hannah Baldwin

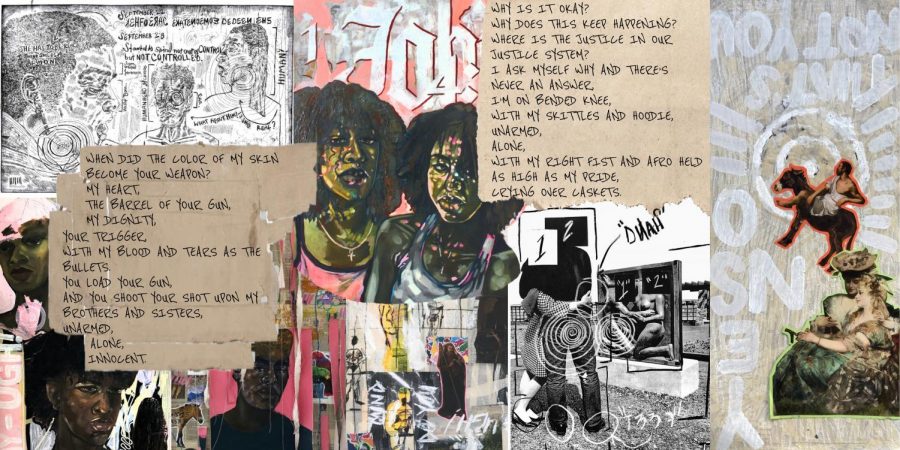

The collage above mixes paintings, prints, and poems by visual seniors Kailyn Bryant and Sabrea Stallings. The poem, “Crying over Caskets,” by Stallings, along with Bryant’s work, incorporates the tumultuous lives and emotions of what it means to be Black in America. Black students, such as Bryant and Stallings, have used their artwork to express their navigation through the current political environment. All of Bryant’s work can be found on her website: kbryantfinearts.com

January 11, 2021

Theatre senior Sabrea Stallings drafted her first spoken word poem, “Crying Over Caskets,” in middle school. Sitting over a lunch table, she scribbled down her feelings as they flooded her mind. The opening sentence: “When did the color of my skin become your weapon?”

Written in 2017, her words remain relevant today. Stallings translated her thoughts about police brutality into art, with lines like “I can’t breathe.” This work eloquently organizes the reality she, and other Black Americans, face into stanzas.

As Stallings sees it, “art is a recreation of life.” Students have channelled their talents into a method of expressing their strife in today’s turbulent political environment.

Deviating from her art area, Stallings has taken up writing as a means for discussing “racism as an umbrella term and the matter of police brutality.” Her works have tackled topics from the “Black man stereotype” to the personal turmoil she faced as a Black girl growing up as a student in predominantly white middle and high schools.

Stallings shared “Crying Over Caskets” at last year’s Black Student Union showcases, where it was performed by theater senior Sarah Grant. Despite it being difficult for her to entrust another with her creation, Stallings encouraged creative interpretation in the performance of her work. The most challenging part of having her art presented for others to consider was being asked to substantially dilute her final piece.

“I had to sensitize it, water it down, because some people believed it would be too triggering, too graphic,” she said. “But that was the whole purpose of it, because that’s the reality of [police brutality].”

Stallings’ work focuses on vividly describing her experiences, and the experiences of others she witnesses. She doesn’t hold anything back from her audience.

“I wanted to make it very realistic,” Stallings explained when recalling her writing process.“I wanted to make listeners sit and think, ‘Wow, this is somebody’s life.’ When I was writing them initially, I wasn’t thinking about impacting people, but now that I go back and look at it, they have impacted people. They’ve caused me to speak out more.”

Her intention in beginning her years-long artistic journey was simple — to release her thoughts and experiences as a Black woman, but it has since grown into something more.

“I went through an identity crisis where I hated being Black. I tried to fit in with a culture that was never meant for me,” Stallings said.

Ultimately, however, she grew tired of trying to wash away who she was, and put her focus towards using her poetry to stand up for herself and others. Her artwork has acted as a catalyst in spurring her political and social involvement.

“I’ve reached out to other Black students and asked ‘What do you want to change?’” Stallings said. “I have an 11-year-old little brother and I would hate to be away at college and know something happened to him. I have to change this.”

Visual senior Kailyn Bryant has also meshed politics with her artform.

“My work has always been semi-political, but this year [my work] has been extra political,” Bryant said. “I get most of my inspiration from the world around me. Definitely just from this past summer I have focused a lot more on political [art] because it’s what’s been going on, or at least what has been highlighted.”

In response to the events that catalyzed a resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement this summer, Bryant is in the works of finishing a 9-by-8-foot painting she titles “Strange Fruit Hanging,” in reference to the poem “Strange Fruit.” Provisional sketches of this piece depict a black man and woman, seated amidst evocative colors.

“Back in June, I was thinking a lot about my place in society and if I was going to be the next Black person to be killed,” she said. “I’m calling it the modern-day lynching, where now it’s more by guns and not necessarily literal hangings.”

Bryant often plays with the scale of her pieces in order to make them feel overwhelming, reflecting the nature of her topics that emphasize “being suffocated by societal ideals.” Overall, her intention in creating art that combines all sorts of mediums is to bring awareness to her subject.

Another piece, “Leopold and Victoria Meets Congo,” moves beyond the realm of current politics and contemplates long-standing ideas about race. It comments on the impacts of colonialism, on the forceful intertwining of cultures.

“[It] is a wearable performance piece where I combine the oppressor and the oppressed,” Bryant said. “I made this piece in reference to my own family lineage but put it into a more current landscape by photographing it at Lake Worth Beach. It was a process where I had to do all this research on both the Victorian Era and things happening now.”

Outside of physically creating art, Bryant has utilized her artistic knowledge to get involved in the political sphere. Alongside theatre senior Mayah Bernstein, she co-founded the website Embrace Black Voices, a resource platform where they spotlight Black creatives of the past and present as a way to highlight their oftentimes underappreciated work. They then partnered with visual senior Auguste Wood to plan Dreyfoos’ Equity Parade.

“I’ve also joined forces with this organization called The School of Now. We are a national organization — we just started — and we are holding conversations through Zoom and Instagram Live talking about current issues. We are about to do one about voting. While we are all artists, our goal is to bring arts and [politics] together. “

According to Bryant, there wouldn’t be art without politics. She explains that while the two may not be inherently intertwined, they rely heavily on one another.

“Certain types are observational, but other types, kinda like my art, couldn’t exist without some type of global landscape.” Bryant said. “The political landscape we are in is just enhancing it.”

When asked how she believed art has impacted the political climate, for better or for worse, she expressed the perspective that its impact is ultimately about interpretation.

“With my art, it probably helps society,” Bryant said. “I’m sure people that might not agree with my politics would probably see it as a detriment. It’s very subjective. You can think your art is doing one thing, but then someone else points out something completely different. One thing I would say is, don’t see it as me bringing down society, I’m just deciding to showcase the things that are often drowned out by the media. That’s my personal liberty.”

Find more of Kailyn Bryant’s art on her website.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)