Breaking a ‘Culture of Silence’

Community conversations bring light to racial inequality in district

Kyla Pelham

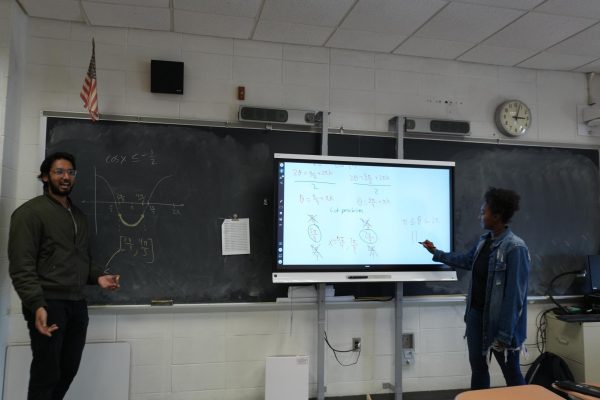

Students, alumnae and faulty have been involved in conversations regarding the impact of race on students’ experiences at Algonquin.

April 1, 2021

“In towns like Southborough, insidious racism is like oxygen in the air. It may stand out in extreme cases — but we grew up breathing it.”

This quote was part of a widely-shared article titled “We Grew Up With an Officer Involved in Rayshard Brooks’ Murder. We’re Not Surprised,” published on LEVEL (a publication from Medium) in June 2020 by Caroline and Emily Joyner (graduates of ARHS in 2011 and 2008 respectively). The article recounted their experience as biracial Black girls at Algonquin and their opinions on the role the community played in harboring racism.

In addition, the Joyner sisters wrote about how towns like Southborough and Northborough may have contributed to the upbringing of white supremacists like Matthew Colligan, a 2008 ARHS graduate who was photographed attending a “Unite The Right” rally in Aug. 2017, in Charlottesville, Virginia which was condemned for its racism and violence. The article also focused on Atlanta police officer Devin Brosnan, a 2012 ARHS graduate who was at the scene of Rayshard Brooks’ murder. Brooks, a Black male, was shot to death on June 12, 2020 by fellow Atlanta police officer Garrett Rolfe while running away after resisting arrest. Brosnan was charged with aggravated assault and breaking three police officer oaths.

Why are racial issues being talked about?

The resurgence of the Black Lives Matter Movement in the summer of 2020 sparked conversations regarding race and inequality across the globe. The movement also prompted a new wave of activism in the Northborough-Southborough community that included Black Lives Matter protests as well as the Joyner sisters’ article.

I think every educator in the building can reflect back on things they could’ve done differently or better when they were teachers earlier in their career.

— Principal Sean Bevan

The article placed the issue in the context of Algonquin, forcing many readers to face that racism is a problem that does not only occur in the deep South.

“We wrote this article from a moment this summer that was a culmination of this very public grief going on with the racial uprising, the murder of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and countless other people at the hand of white supremacy,” Caroline Joyner said in an interview via Zoom. “It was an opportunity to use something that was very public to talk about something that we haven’t talked about publicly for years. [Talking about race] has been something we have been struggling with in the past, but something I’m glad Algonquin is taking on.”

Six months after the article was published, the Joyner sisters reflected on the actions the community should take to make a change.

“I think it’s up to the school and up to the community to take the lessons in our article of how there is a culture of silence at Algonquin and learn to dismantle the structures that keep white supremacy alive in the town and the district,” Caroline Joyner said.

Principal Sean Bevan, who had Emily Joyner as a student when he was an English teacher at Algonquin from 2002 to 2009, believes their article prompted many Algonquin educators to look at how they personally have dealt with race.

“I think [their article] was a very powerful, really well-written piece, and it forced a lot of adults in our school community, myself included, to reflect on whether or not we’re doing the best thing to educate all of our students about the issue of race in America,” Bevan said. “I think every educator in the building can reflect back on things they could’ve done differently or better when they were teachers earlier in their career.”

Racial bias at Algonquin?

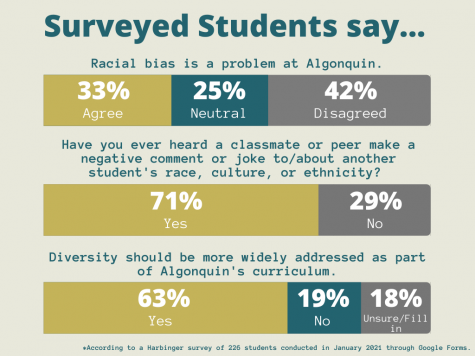

Students have varying perceptions of the level of racial diversity at ARHS, and as of the 2020-2021 school year, the Algonquin student population consisted of 75% white and 25% Black, Indigenous or people of color (BIPOC). In a Harbinger survey of 226 students conducted from Jan. 17 to Jan. 24 through Google Forms, 56% of students disagreed with the statement “Algonquin is racially diverse,” while 24% agreed and 20% were neutral.

“Obviously, Algonquin is not a very racially diverse place,” senior Sarah Saeed, a Pakistani American, said. “It’s odd because my perception of myself as a person of color is skewed because I’ve grown up around white people all the time, and at this school, it’s mostly white people. I constantly recognize myself walking into a room and being the only brown person there.”

Freshman Sadhya Kanal, who is one quarter Indian, with a Hungarian-Indian father and an Irish-Scottish mother, has experienced racism and racial bias growing up in the boroughs.

“Growing up in Southborough, a primarily white community, I was not treated well because of my race,” Kanal said. “I don’t look it, but my name is Indian. For some reason, my peers couldn’t associate looking white and having an Indian name. For some reason that is not normal to them, and they can’t accept that. It was definitely something I was bullied for.”

As someone who is part Asian and part white, freshman Jack Cheney had similar experiences with racism.

“When I was in middle school, some people made fun of my eyes and said things like, ‘You can’t see,’” Cheney said. “I try not to take it too hard because I try not to show too much emotion, but it does hurt a lot.”

Kanal and Cheney are just some of the students at Algonquin who have experienced negative comments regarding their race. In fact, 71% of survey respondents said they had heard a peer make a negative comment or joke about another student’s race, culture or ethnicity. However, when asked if racial bias is a problem at Algonquin, 42% of students who responded to the survey disagreed, 33% agreed and 25% were neutral.

Kanal, who has also been a target of these negative comments, believes more education about race should be implemented to address them.

“I mean, being raised in a mainly white community, it’s hard to shy away from [negative comments],” Kanal said. “I think incorporating [anti-racism education] more into the curriculum will help with the negative comments. It will teach kids race is not something you should be bullied about.”

What has Algonquin done?

With the upsurgence around the topic of race, multiple Instagram accounts such as @bipocalgonquin and @united.lly have popped up in an attempt to bring light to the issue in the ARHS community.

The bipocalgonquin account is a space for the voices of BIPOC students and their experiences with discrimination or racial bias at Algonquin. United.lly, on the other hand, is an organization striving to advocate for BLM, LGBTQ+, women empowerment and mental health.

Additionally, this year the Public Schools of Northborough and Southborough’s Coalition for Equity was created in an effort to encourage conversation about racial inequality within the district. The Coalition is composed of ARHS students and alumni, as well district administrators, educators and parents who expressed an interest in the coalition and cause.

According to an email from Bevan sent to faculty in October, “the Coalition focuses on issues of equity within the district, creates the conditions for conversations to support collaborative learning about inequality and identifies and develops resources to support learning and action.”

There are four subgroups within the Coalition: curriculum, instruction, policy and community outreach. English teacher Emily Philbin is a member of the coalition’s curriculum subgroup.

“We are figuring out ways that we can help teachers assess their curriculum, as well as their own instructional practices for areas of bias or to see whose voices are being left out,” Philbin said. “My group is doing a bunch of research, and we’re looking for some sort of tools to assess these things.”

Another aspect of this push for increased awareness of race and diversity is a close look at changing Algonquin’s Tomahawk mascot.

The Tomahawk has long been the subject of much controversy, and with increased concern about race and representation, along with a petition started last summer (with 5,085 signatures as of March 8) by recent alumni, Bevan has created a mascot study group and has held focus groups with students. The study group of 16 stakeholders, including students, parents, alumni, educators and administration, aims to determine whether or not the mascot should be changed and when and how the potential change should be carried out.

However, some stakeholders are frustrated with the slow rate of change.

“I’m part of the mascot study group and the Equity Coalition, and for me it seems like a little bit performative,” Saeed said. “I think the intention is there to do good for the racial inequality at Algonquin, but it feels like it’s not really moving.”

One racial justice committee is not going to be your answer.

— Emily Joyner, 2008 Algonquin alumna

Emily Joyner is also concerned about the continuing discussion without apparent action.

“One racial justice committee is not going to be your answer,” Emily Joyner said. “We can have conversations and discussions. But there needs to be transparency from the administration about what specific steps they are taking. We can talk about difficult dialogues, we can talk about having conversations all day long, but what does it mean for actual actions?”

Philbin agrees that the Coalition could move at a quicker pace, but she explained that not everyone has the basic understanding of race and racial issues yet.

“What is hard is everyone’s kind of on a different stage of the journey of understanding what we need to do,” Philbin said. “And so there are some people, and I put myself in this category, who are maybe a little further along, and there are others who still have to piece everything together… I can understand and share in the frustration about things just being conversations, but I’m hopeful that despite a slower start, we’re going to start to have more action plans.”

What should Algonquin do to address race and racial bias?

In order to address race and racial bias, many students believe the solution could be incorporating the topic into the curriculum. According to the Harbinger survey, 63% of students believe diversity should be more widely addressed as part of Algonquin’s curriculum, 18% of students do not and 19% were unsure or provided filled responses.

“One thing that stands out to me is that almost every book we read in required English classes are by old white men,” Saeed said. “I know there are electives that take it beyond that and explore other cultures, but I think we should have required readings about Black people, about other people of color that are not all about the struggle. If we do read something about Black people, it’s about slavery, it’s about the torture they face. I think we need to read about Black people in uplifting experiences. I think that the student-led things like some of the projects for Silenced Voices (an English department elective) are really good because they are making facts known that people don’t know much about.”

Emily Joyner notes that the issues explored in the English and Social Studies electives need to be acknowledged by those that are not just volunteers that take such courses.

“There’s going to be an obvious pattern in who’s taking those courses and who feels the need to and who doesn’t, and that’s a very concrete systemic example of how even actions that are taken to potentially make Algonquin a more equitable place still continue to perpetuate the same thing by making it volunteer-based to learn about Silenced Voices or a Race in America course,” Emily Joyner said.

Philbin, who teaches Silenced Voices, also sees a pattern in her classes where most of the students often agree with one another in discussions without having opposing views.

“I don’t think that Silenced Voices is enough,” Philbin said. “I also think that kids who are already thinking about these ideas take that class because they have an affinity for the subject. They discuss [but] it’s rare that there are differing opinions.”

Caroline Joyner holds that it is the white faculty who need to overcome their discomfort and take on the responsibility of weaving studies of race and racism throughout the curriculum.

“We shouldn’t set just one unit aside to talk about race; it should be an ongoing conversation,” Caroline Joyner said. “It shouldn’t be talked about like it is a thing of the past. It’s uncomfortable to interrogate a system that benefits you. I think that white faculty are uncomfortable talking about the system that benefits them too. That takes real sensitivity training, it’s not just something you can do, it has to be something you are very intentional about. That intentionality is lacking and also the effort to educate themselves is something that also needs to happen, and it’s not on Black people to do that.”

According to Bevan, starting this year, there has been more of a push to educate administration and teachers in the district about racial equity. The district has undertaken equity as an area of focus and completed training, conducted by the Coalition for Equity, in Nov. and March.

“The focus is really on asking teachers to reflect on their own experiences with inequity or to reflect on how their upbringing, training and experience have contributed to understanding equity and inequity more, and how they might self identify where are ways that they can grow,” Bevan said. “So we’ve committed almost the entirety of our training or professional development to this topic.”

It’s a systemic issue, so it’s so overwhelming, but every system needs to be interrogated.

— Caroline Joyner, 2011 Algonquin alumna

However, some students believe overtly addressing race and diversity in classes could be counterproductive, according to the anonymous fill in option of the survey question “Do you think that race and diversity should be more widely addressed as part of Algonquin’s curriculum?”

“I think that race should be incorporated in the fabric of the learning, to acknowledge that whites have had an easier go of things,” an anonymous survey respondent said. “However, when this is taken to the extreme, and classes serve the purpose of ‘wokeness’ and ‘white shame,’ you degrade the very cause you are trying to garner support for.”

Other students believe the topic of racism should not be addressed at all.

“I don’t think we should bring attention to a ‘problem’ unless those affected/suffering from inclusivity have complaints and feel uncomfortable,” an anonymous respondent said.

Caroline Joyer agrees that addressing race and racial issues can be a controversial matter, but she believes that they shouldn’t be overlooked.

“It’s a systemic issue, so it’s so overwhelming, but every system needs to be interrogated,” Caroline Joyner said. “I think that when people get overwhelmed, they just give up sometimes, but that’s not what should happen because it will perpetuate for eternity.”

This story was originally published on The Harbinger on March 31, 2021.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)