Netflix’s “The White Tiger” walks the line between scathing and safe

Hilary Weisburd '21

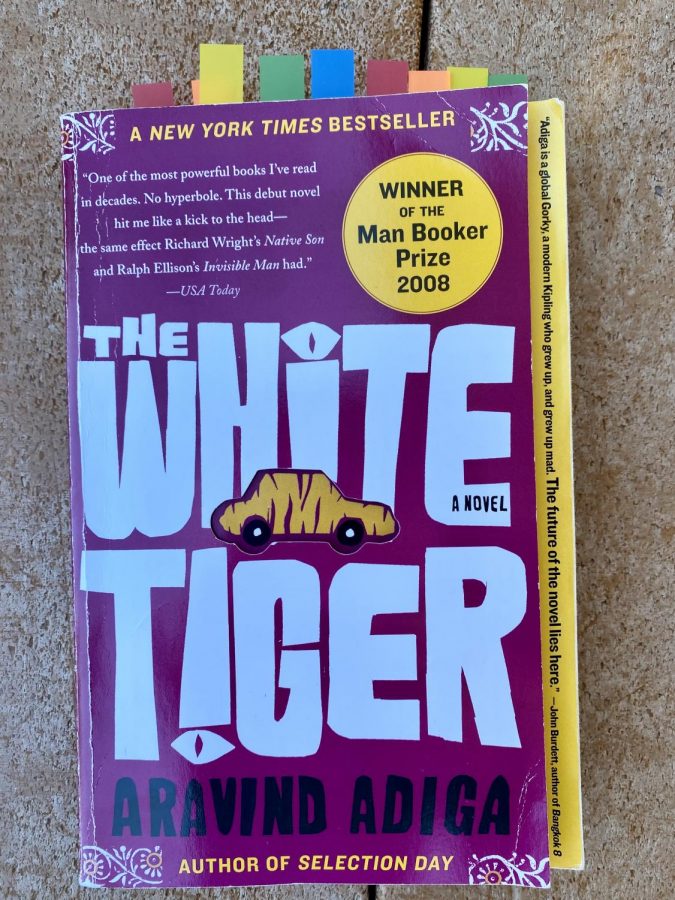

“The White Tiger,” a RE junior year favorite, is transporting individuals to India with a new movie.

April 13, 2021

A staple of Ransom Everglades’ eleventh-grade English curriculum, Aravind Adiga’s The White Tiger has left its impact on generations of RE students. Themes of faux morality, hypocrisy and class inequality give this story its cynical edge, creating a searing commentary on the brutality of class struggle as exemplified in India’s caste system. The novel illustrates rage and resentment both at the cruelty of those at the top and the complacency of those at the bottom.

On Jan. 13, director Ramin Bahrani’s film adaptation of Adiga’s iconic work found a new home on Netflix. The core themes of the novel are alive and well during the film, albeit weakened by Bahrani’s editing out of the novel’s darker moments.

The film, like its namesake novel, centers around Balram Halwai (Adarsh Gourav), an Indian sweet maker trapped in a lower caste. After the death of his father, Balram begins his struggle to rise to the top, eventually finding work as a driver for the son of his village’s former landlord, Ashok (Rajkummar Rao). His relationship with Ashok, as well as his wife Pinky Madam (Priyanka Chopra Jonas), begins mostly positive compared to the typical treatment of the lower caste by the wealthy, but slowly degrades over the course of the film.

The strength of the narrative lies here, in the slow breakdown of Balram’s psyche and restraint with each demand Ashok makes of him, ranging from the inane to the insulting, as a much more successful version of himself narrates the tale, breaking down the elements of religion, social structure, politics and culture that serve as the film’s background.

It is in that regard that the film adaptation works as well as it does. While Balram’s narration is in English, the language spoken by his wealthy employer Ashok, his conversations in real time are in Hindi, immediately signaling the difference between the two versions of himself. After his falling out with Ashok, Balram slowly begins to change his wardrobe, adjusting his hair and wearing cleaner outfits. Whenever Balram the narrator tries to rewrite himself to be more sympathetic, the real Balram grants a clear view of his true feelings and intentions.

The divide between these versions of Balram, both in language and behavior, is reflective of the differences between the Light, the supposedly virtuous higher castes and their cities, and Darkness, the immoral, poorer villages of India. The film clearly defines this split through use of muted colors and traditional music while in the Darkness, contrasted with the originally vibrant lights and homogenized, popular soundtrack of Delhi. The architecture is clearly separate as well, with the crumbling homes and dusty floors of the Darkness making the clean roads and modern buildings look even grander, and the streets are much more crowded, allowing for a blunter depiction of the divide than was given in the novel.

However, for all its enhancements, the film struggles with the cynicism so present in the original novel. Bahrani creates more sympathetic characters in Balram and Pinky by suppressing or removing their darker moments.

During Pinky’s departure for America, she leaves behind an envelope of money, with around 4,700 rupees inside, as Balram is left to piece together the truth of why she left him such a specific number. Eventually, he correctly affirms that Pinky repeatedly revised her gift, leaving him with less than half of the original sum she had set aside, painting Pinky’s faux morality as no better than her ex-husband’s. In the movie, the amount changes to 9,700, which illustrates the greed of Pinky’s actions while transforming her into a more sympathetic character.

The film also establishes Pinky as having come from a very poor family in the United States, eventually rising up to become a college graduate. It draws parallels between Balram and Pinky, which likens her to the audience. Despite her kinder actions as Ashok’s wife being born of self-serving pity for Balram, she becomes a well-meaning bridge between both men.

Balram’s ending follows the trend of revised heroism, removing his death threat towards his nephew and only living relative, Kusum. Instead, the film depicts the entrepreneur as a clear upgrade from Ashok and his kin, a businessman who treats his workers as employees, not servants. The commentary on India’s higher caste being filled with corruption is somewhat weakened by this change, as Balram becomes more of a beacon of change for the system.

For all its problems in portraying its characters in the script, the actors perform their roles beautifully. Gourav’s portrayal of Balram is hauntingly raw, delivering cruelty and selfishness around his peers, made worse by his heel-face turn to groveling pleas before his employers. He breathes new life into the character, being an Indian underdog himself, and Balram’s rage and resentment are palpable as he forces himself to smile when turned into a scapegoat for Pinky’s crimes.

All the leading actors humanize their performances, as Pinky and Ashok are both chillingly efficient in switching between the desire to do good and the need to be in complete control. Ashok’s father and brother, played by Mahesh Manjrekar and Vijay Maurya respectively, are equally as haunting in their performance around Balram, making the audience truly believe that they see him as a tool, something beneath them, abusing the driver as one would a rowdy pet.

Director Ramin Bahrani’s work in finding Gourav, a relatively unknown Indian actor, helped give the movie one of its strongest positives as well as add to his role as the story’s underdog. While the struggle between telling an accessible story through the narration and an intimate one through the characters’ interactions is clear, Bahrani weaves it together by knowing when to rely on Balram’s explanations and when to let the drama speak for itself.

His choice in cinematographer paid off as well, as Paolo Carnera uniquely captures the state of Balram’s deteriorating mind through unnatural angles during his breakdown, taking a typically steady camera and twisting it around him, shaking as it moves.

The use of color plays a large role in the film, as the vibrant blues and reds of the modern-day Balram serve as a clear indicator that, compared to the dull browns and beiges of the Darkness from which he came, he has left the lower caste behind.

Expanding upon the theme of the Darkness and the Light in India is the muting of colors, something very present in Balram’s childhood in Laxmangarh. Originally, this was reserved for the Darkness, which Balram wanted to distance himself from because of his distaste for it, but as he becomes disillusioned with his work as a driver and sees the corruption and cruelty of the so-called Light, Delhi becomes muted as well. By the end of his time there, the only prevalent warm color left is the red of the bag of money, symbolizing his hope to create his own Light.

Despite its issues with tone, Netflix’s The White Tiger is a wonderfully intense film that aptly conveys the problems of Balram’s world. Through its actors, the human drama comes alive, and their performances almost single-handedly create an adaptation that never lets the audience rest. It allows for a clearer look at the inequality between the Light and Darkness of Balram’s India, as well as the clear divide between Balram’s self-righteousness and his true ambitious nature, and will no doubt be a staple of the English courses at Ransom Everglades.

This story was originally published on The Catalyst on February 10, 2021.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)