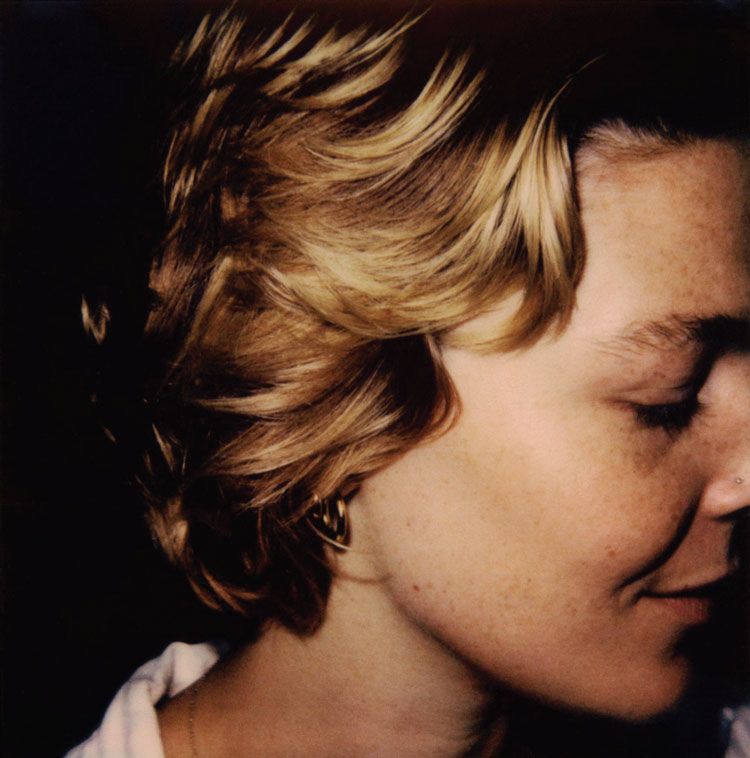

This Student Can Translate Hieroglyphics. And Speak Six Languages.

May 3, 2021

A pile of misaligned papers sits cluttered on the edge of a desk.

From far away, it looks like nothing more than handwritten school notes. But at a closer glance, every blank space of the notebook papers is filled with distinct illustrations.

Junior Havanna Eleyadath explains that the seemingly gibberish word she drafted in the center of her paper, “Fyrirgefðu,” translates to “Excuse me” in Icelandic, while the half-bird/half-man hieroglyphic sketched on the corner represents the “Ka,” or “soul” in Egyptian.

Being of partial Indian descent, Eleyadath’s language journey first started with Malayalam, an ancient language spoken natively by over 38 million Indians. Although she was not formally taught the language, she has reached a high speaking proficiency through conversations with relatives.

“A lot of parents in Asian culture would teach children their home language, but my parents didn’t really give me extensive training on that,” Eleyadath said. “I still can’t read or write in Malayalam, but I think since it’s such an ancient language and coming from an ancient language in Sanskrit, that fueled my interest in ancient languages from the Mesopotamian eras and the Egyptian eras.”

Eleyadath grew fascinated by the abstract illustrations depicted in Egyptian hieroglyphs, and by the age of four, she cultivated her interest in Egyptian culture with regular trips to the library to clear out books about ancient Egyptian religion, culture and historical records.

“I wanted to read this weird language that I wanted to build on,” Eleyadath said. “Plus, I liked drawing back then. I was drawing and drawing and drawing until I could actually make a print copy of what was written on the walls on the paper.”

Today, Eleyadath adamantly studies Egyptian historical figures, including infamous queen Neferneferuaten Nefertiti, and interprets ancient Egyptian texts like the Rosetta Stone. She draws most of her inspiration from documentaries like “The Real Origins of Ancient Egypt,” following archaeologists’ journeys and extracting artifacts from the past.

“I had nobody to teach me. I had no one to lead me nor to guide me. I did it all by myself, and I don’t want that to happen to other people,” Eleyadath said. “Being that teacher figure is really important to me to other people in the future since I know the struggle of teaching yourself.”

Eleyadath said she hopes to further her interest in Egyptian culture by traveling to Egypt when the pandemic subsides and plans to take a gap year during college to participate in an Egyptian archaeology expedition.

And still, Eleyadath’s linguistic interests extend beyond Egyptian hieroglyphs and Malayalam. She also devotes time and effort to learning the esoteric languages of Icelandic, Gaelic, Latin and Welsh. Only 57,000 people in Scotland speak Gaelic, according to the 2016 Scottish census, and roughly 300,000 people speak Icelandic, according to the Icelandic Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

In a globalized world where lingua francas like English overshadow uncommon languages, Eleyadath recognizes the importance of preserving endangered languages and engaging with minority cultures.

“If a person speaks your language, you can connect with them more,” Eleyadath said. “I want to know people’s stories. I want to know people’s wisdom. What do they have to say?”

This story was originally published on Portola Pilot on April 9, 2021.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)