‘I hate to say this, but I was bullied for my race’

We need to do more to support people of color at LFHS

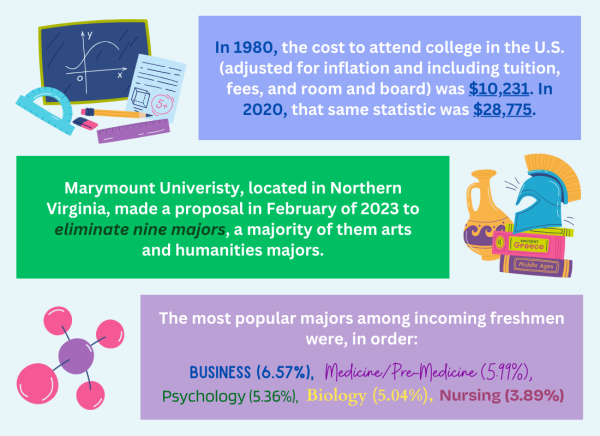

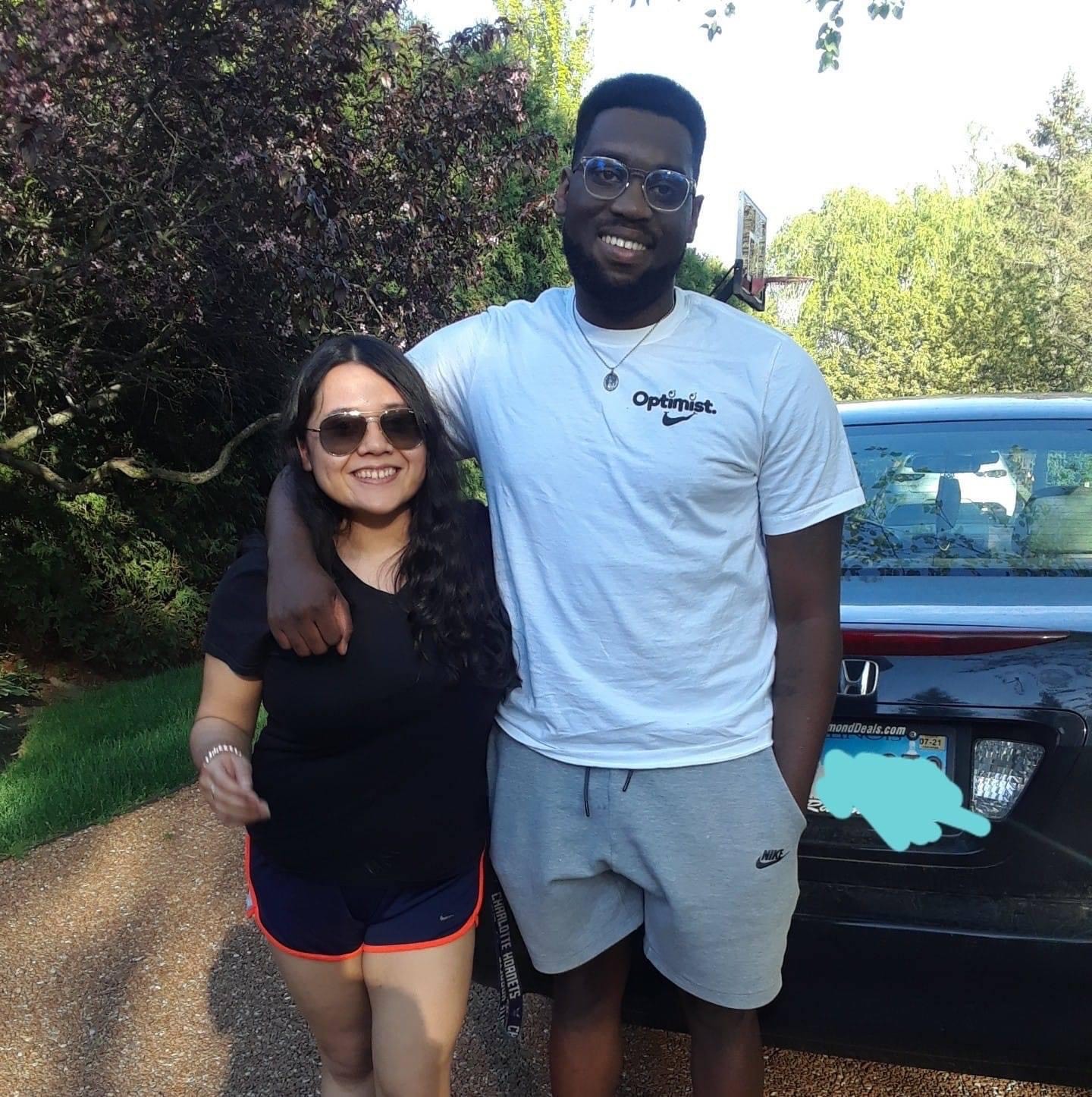

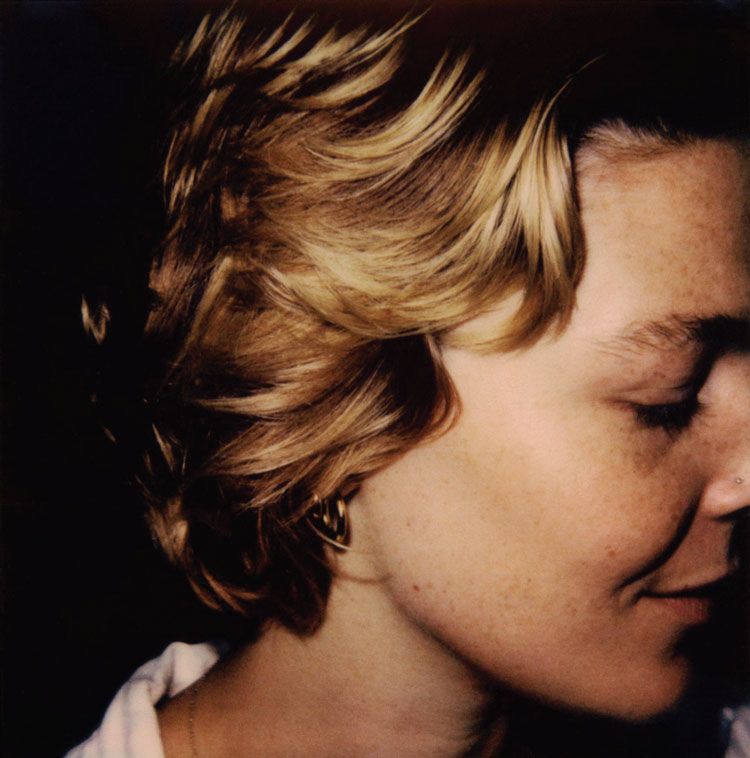

Courtesy of Charlie Kiernan

Charlie Kiernan, class of 2017, hopes his story can help make LFHS an environment that is more supportive of minority students.

June 3, 2021

Charlie Kiernan says the students, some of them his friends, would point their fingers like a gun at him and yell,“Hands up, don’t shoot.”

Kiernan, class of 2017, would say, “Oh, you got me,” and let out a nervous laugh. It became routine.

The students were mocking the slogan “Hands up, don’t shoot,” which is associated with the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. The phrase became a rallying cry for the Black Lives Matter movement.

“I was 17 or 18 at the time, so, of course, I knew what racism was. But I try to look back on it and ask if they were bullying me,” Kiernan said. “It was always hard to admit because I thought these [people] were my friends.”

Kiernan says he has since come to terms with how some of his peers treated him in high school, but when he was a student here, he disregarded the comments in order to fit in because these were his “friends.”

“I hate to say this, but I was bullied by the kids and was constantly bullied for my race. This is my first time admitting it. I know I was bullied, but I would try so hard to defend these people. I would say ‘no these are my friends, they’re not bullying me.’”

Prior to high school, Kiernan played recreational football with some of his classmates. There were some kids who would make comments that Kiernan didn’t understand at the time.

“As I got older, I understood the damage of these racial phrases,” he said. “I remember as a kid a teammate would call me a monkey or an animal, or say my lips are very big. They would make it sound like we were all roasting each other, but it felt more personal than that.”

There is nothing micro about these aggressions

Microaggressions is a term commonly used to describe the type of insults or jabs that were thrown Kiernan’s way.

“Microaggressions are defined as the everyday, subtle, intentional — and oftentimes unintentional — interactions or behaviors that communicate some sort of bias toward historically marginalized groups,” said Kevin Nadal, a professor of psychology of John Jay College of Criminal Justice, in a 2020 interview with NPR..

Whether intentionally harmful or not, the impact of such comments reveals the pervasive stereotypes about a particular race, culture, gender, sexual orientation or ability.

“At the end of the day, if somebody says something racist to you, it’s racist. And if it hurts your feelings, it hurts your feelings, so it doesn’t really matter what we define it as,” said Nadal.

The best way to break down these stereotypes is to develop relationships with those who belong to social groups different from your own.

The term, however, does not do justice to the harm it does to BIPOC. There is nothing “micro” about these aggressions. A statement such as, “you are the whitest black person I know” is harmful, even if it is not said with ill-intent. It makes clear the expectation to fulfill a racial stereotype. These racial stereotypes have pervaded society for years, and now have become normalized in our society.

“Some offensive language and speech has become greatly normalized in the past few years that these things can be said without being confronted by the offended party for a long time,” said Principal Dr. Chala Holland, “Sometimes people offended by certain statements will not say anything because they are afraid it can fracture a relationship.”

The best way to break down these stereotypes is to develop relationships with those who belong to social groups different from your own. Without these relationships, people are only left with stereotypes on which to base their perceptions of BIPOC.

The absence of these relationships means that outside research is required to understand that the stereotypes perpetuated by the media offer singular narratives about an entire social group, rather than diverse stories of personalities, values, and interests represented in every social group.

“I work with a lot of students of color, and a big struggle for a lot of them is that there are assumptions made about them on a day to day basis,” said social worker Maggie Harmsen. “Consequently, these assumptions made by their peers make it harder for them to be their true selves.”

Living in a generally homogenous town makes it more challenging to develop meaningful relationships with BIPOC. For the LF/LB community, along with society as a whole, we need to unpack what role racism has played in our own lives, and hold ourselves and others accountable.

For our community, accountability plays a part in moving forward and to prevent experiences similar to Kiernan’s from happening again for BIPOC students at LFHS. Accountability, in part, comes from self awareness, which comes from developing meaningful relationships and confronting the uncomfortable topic about racism in our own lives and the community as well.

If you are unsure of whether you want to conduct this research and start this process of accountability. Reflect on this question: Are you currently content living in our own bubble? If you are, that’s how most people are. They don’t want to confront the uncomfortable. But, if we want to break apart from this bubble, it’ll require holding ourselves accountable and putting in the time to educate ourselves about the systemic inequities (racist policies) that have led to living segregated lives and reinforced the stereotypes that persist today.

The Pressure to Fit In

Kiernan says he spent his years as an underclassman avoiding social interaction because of the way his peers saw him. He felt pressured to fit the stereotype of “the black kid,” with his peers in order to fit in. The pressure Kiernan made it hard for him to turn to his peers or to find someone who he could relate to for being him.

“I stopped trying to branch out because I wanted to only be referred to as Charlie or the kid who likes to write, or something like that. Not the black kid,” Kiernan said. “It seemed like every single kid at Lake Forest High School had an identity, but for me, it felt like my identity was just [being] the black kid.”

“I stopped trying to branch out because I wanted to only be referred to as Charlie or the kid who likes to write, or something like that. Not the black kid,” Kiernan said. “It seemed like every single kid at Lake Forest High School had an identity, but for me, it felt like my identity was just [being] the black kid.”

Once Kiernan became an upperclassman, he tried to fight back against the surface-level identity that his peers placed upon him.

“I wanted to be referred to as Charlie, and really tried to form my own identity.”

As the years progressed, Kiernan says he struggled with trying to find someone he could relate to and understand who he was. Instead, Kiernan had to fit the box placed on him by his peers because of the lack of understanding from the community, including staff members.

Kiernan said he reached out to his support staff but was never able to make a strong connection with them. Kiernan spent a lot of time in the social worker’s office during class, which was interpreted by some staff as ditching class, when in truth, Kiernan said he was avoiding kids in class who were making him uncomfortable with their comments.

Kiernan initially downplayed the harassment from his peers. However, when it became too much, Kiernan says he went to his dean to report the harassment. Although the support staff and deans do their best to address certain issues, they can fall short sometimes as well despite their good intentions.

“I don’t remember all the details of what happened with Charlie. But I can say that if we had known about the situation, we would have addressed it every single time that it happened,” said Kiernan’s dean, Frank Lesniak.

When students are addressed about their behavior, they may not necessarily change. For many students, they don’t realize what they have said is inappropriate or offensive until it is brought to their attention by other people, including students and staff. According to Lesniak, when their behavior is addressed, students will learn from the experience and become more aware of their language.

“It seemed like every single kid at Lake Forest High School had an identity, but for me, it felt like my identity was just [being] the black kid.”

However, there are other circumstances where students may not think their remarks are a big deal because they meant it as a “joke” and did not mean to hurt others. Because of this, many people continue to say things that may offend others, despite their peers telling them about how their remarks may be offensive.

“There were various teachable moments of progression and growth by everybody [since I’ve graduated],” said Kiernan, “However, due to nobody being held accountable for their actions I not only had to endure [racism], but many of the same individuals left the school with those same ignorant and out right racist thoughts and actions. It becomes very difficult to show [the students] that their way of thinking is not plausible.”

Developing relationships with BIPOC causes students to breakaway from the stereotypes that perpetrate the school surrounding BIPOC, and understand the impact of our words, regardless if they are “jokes.”

LFHS Four Years Later

Since Kiernan graduated in 2017, the district has worked on promoting diversity: the boys and girls diversity groups that Maggie Harmsen runs, embRACE Club run by English teacher Mrs. Amy Lyons, diversity classes for teachers, and other initiatives proposed by Harmsen and her colleagues. However, the process takes time and the progress will not always be linear.

“Yes, we have a lot of work to do. But, we are taking steps in the right direction,” said Harmsen. “We want everybody to feel welcome and safe at LFHS. And by everybody, we mean every single person. All students and staff, and not just certain people in the school.”

Whether inside or outside LFHS, to prevent experiences such as Kiernan’s from happening again for BIPOC students, accountability will be key along with conducting your own research if you lack relationships with BIPOC.

“If me telling my story and sharing what I went through can help future students from experiencing the same thing,” said Kiernan, “I’ll take it.”

This story was originally published on The Forest Scout on May 26, 2021.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)