Military brats

Military school students found schools on military bases often had higher academic rigor and a stronger sense of community.

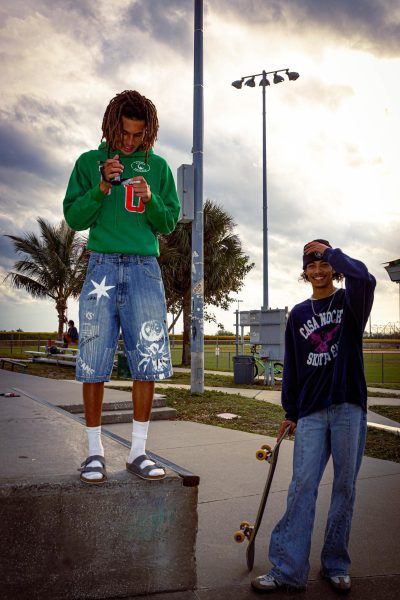

Joelle Jackson

Joelle Jackson and her sister at Fort Polk in Louisiana. After living abroad in Wiesbaden, Germany, she moved back to the US.

October 22, 2021

Instead of an alarm clock, sophomore Joelle Jackson wakes up to the sound of a military horn, blaring at spaced time intervals to signal soldiers of roll calls, meal times and personal training.

That was her reality for five years — living and going to school on a military base. Born in Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, Jackson spent preschool to fourth grade at military schools, otherwise known as a Department of Defense Education Activity school.

Like many others, Jackson’s life as a military child involved frequently moving from place to place, a product of her father serving in the Army. With more than 69,000 school-aged military children enrolled around the world, DoDEA schools provide quality education for military dependents, saving families the hassle of searching for new schools.

Drawing on her own experience, Jackson came to the same conclusion.

“Most of the schools were a little more advanced, only because you’re constantly moving. Different countries do schools differently, so they want you to be prepared. I know that there were some things that I learned that were at more advanced levels than other kids would learn in third or fourth grade,” Jackson said.

In fact, these schools on average boast higher test scores than public schools, according to the 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress test.

JROTC Instructor Enrius Collazo, who enrolled all three of his sons in DoDEA schools, says his decision was largely affected by the reality of his military job and the quality of their schooling.

“[Enrolling in] DoDEA schools is kind of like paying for a private school, but we’re not paying for private school, and it’s top notch education,” he said.

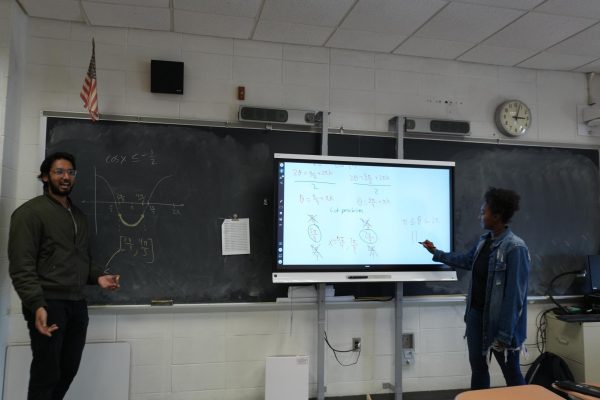

Collazo’s twin sons, Hagerty seniors Andrew and Edward Collazo, agree that DoDEA schools are excellent schools, though diverge on their opinions on whether public or DoDEA schools offer a better education.

In Edward’s point of view, Hagerty’s academics rank above that of military schools. However, in comparison to lower-rated schools in the county, military schools are better, a stark contrast to his brother’s opinion.

“[The military school] was definitely very above what normal schools have. If I took a regular class in a federal DoDEA school, it would feel like I was taking an honors class in a normal school,” Andrew said.

In addition to the level of academics provided, DoDEA schools differ in terms of the teaching. Teachers, who often have spouses or children in the military, are typically more understanding of the challenges that come with being a military child.

“When it came to missing school, they’re a little bit more lenient than the teachers here, because they know that we live so far away from our families,” Edward said.

Other major differences noted between public and DoDEA schools were in behavior and diversity.

“The students on the military base were definitely more respectful. I would say more disciplined in a way, because, of course, they have military parents, so they weren’t rowdy,” Andrew said.

According to him and Jackson, the schools were also more diverse, with students from all over the world sharing one trait: having military parents.

“There’s a whole bunch of different people from different places, so it’s a very inclusive environment because everybody’s used to being the new kid,” Jackson said.

According to the 2020 DoDEA report, student diversity was approximately 41% White, 21% Hispanic, 12% multiracial, 11% Black, and 5% Asian, compared to Hagerty’s 68% White, 18% Hispanic, 3% multiracial, 6% Black, and 6% Asian, according to U.S. News.

This shared trait also creates a bond between the students, since each one of them are familiar with the military experience of moving around constantly.

“The neighborhood I’m in now, even though we’re all one big neighborhood, it’s never felt as close as it has on base. There’s a connection that we have on base that it’s just something you really can’t replicate in a way,” Jackson said.

However, there are disadvantages in attending a DoDEA school, particularly in the extracurriculars available to students. Because military schools are typically much smaller than public schools, that means less clubs and less club members.

“We did have some sports teams but like lacrosse? We didn’t have that,” Andrew said. “We definitely didn’t have all the honor societies that a regular American school does. It was also because some people didn’t live on base, and all the extracurriculars were on base, so there wasn’t always a lot of participation.”

Although Jackson and the Collazos have spent different lengths of time as military children, the experience has made significant impacts on their lives.

“It made me a much more sociable person,” Jackson said. “You would think with people constantly moving all the time you wouldn’t want to be quick to make friends, but I think, since all of us were in the same boat and we knew this was going to happen, we were like, ‘You know what, might as well just make memories while we can.’”

This story was originally published on Hagerty Journalism Today on October 21, 2021.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)