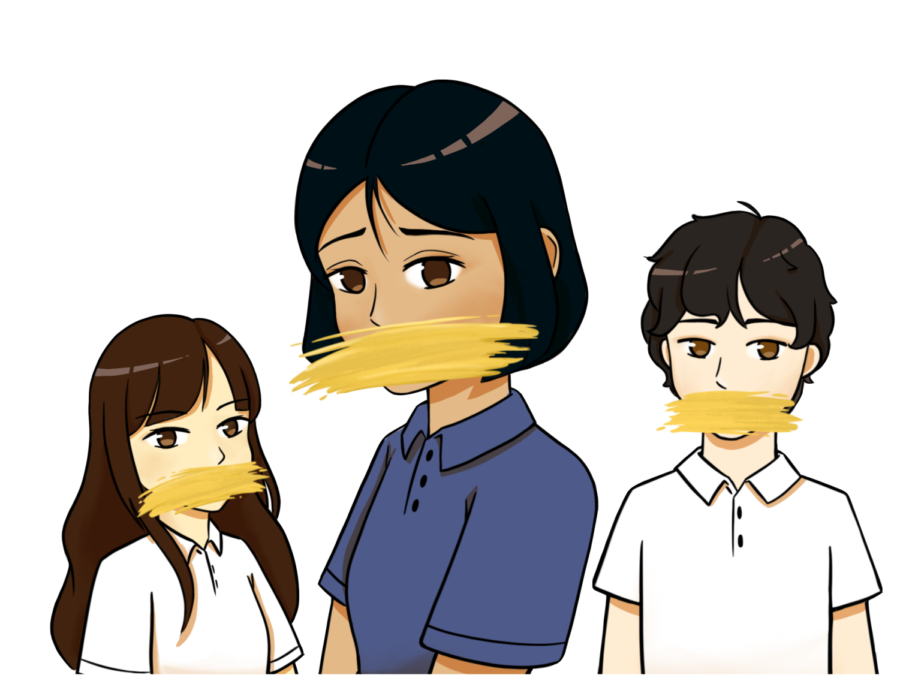

“No matter how much I spoke up, I would only be perceived as being the quiet Asian.”

Alice Xu

Asian Americans are often described as quiet and shy, a categorization that exemplifies the model minority myth.

February 4, 2022

The model minority myth conveys an oversimplification that labels all Asian Americans as polite, law-abiding and scholastically high-achieving — especially in STEM subjects. Believing the myth erases the differences among individuals.

Because Asian Americans are often described as quiet and shy, Chinese teacher Summer Pao has noticed that her extroverted personality surprises others.

“It doesn’t seem to fit the stereotype,” Pao said.

Dian Yu has noticed this categorization in mid-semester comments. Over the years, some teachers have written that she is quiet and needs to “speak up more,” which does not align with her actual classroom behavior.

“They probably confused me with another Asian student because I’m one of the loudest, most participating people in the class,” Yu said.

Rachel Chih has received similar comments from teachers, even for some of her favorite classes in which she is fully engaged.

“When I read some of the comments, I know they’re not talking about me,” Chih said.

One senior girl, who asked to remain anonymous, is one of few Asian Americans in one of her humanities classes. At the beginning of a class last fall, her teacher announced that the class would not be dismissed until she joined the discussion. The incident was shocking and embarrassing because she felt as though she spoke as much as the average person. Ironically, the effort to get her to talk more has dampened her enthusiasm. As a self-conscious person, she is careful about what she says. After being put on the spot, she said, “I don’t want to ever feel like that again.”

Later that day, the teacher approached another Asian American student and told her that she would be next. Other students said that at least one white male student has never spoken up in classwide discussions.

The singled-out senior says that her identity as a female Asian American caused classmates to “diminish” and “ignore” her participation: “It made me feel like no matter how much I spoke up, I would only be perceived as being the quiet Asian.”

History teacher Joseph Soliman has observed outside of SJS that when he, as an Asian American, vocalizes his perspectives, listeners are often taken aback — they expect Soliman to be a “bystanding listener.”

“I speak up about political issues or whatever topics are at hand,” Soliman said, “and I’ve noticed that some people are surprised that I would speak up as quickly as I do.”

It made me feel like no matter how much I spoke up, I would only be perceived as being the quiet Asian.

The model minority myth also places pressure on Asian American students to earn high grades. An A-minus was dubbed the “Asian F” in a 2011 episode of “Glee.”

“In the context of school, Asians are seen as the smart kids and good at math,” Maria Cheng said. “We’re seen as homogenous.”

Phan notices how many of her classmates assume that all Asians are smart and can be consulted for assistance in any class. Throughout Middle and Upper School, classmates have approached Phan, expecting her to know the answers.

“People joke about it, but it’s not funny,” Phan said. “They keep saying things like ‘you’re Asian, so you should know this.’”

Mark Doan has experienced similar requests since fourth grade, regardless of his comfort level with the relevant material.

“I don’t know how a stereotype like that is grounded in the mentality of so many students, but it’s there, and it’s spreading toward all age groups,” he said.

When Ariana Lee was in Middle School, she was studying for a test when the classmate sitting next to her asked to borrow her study guide. When she told him he could have it once she was done with it, he said, “but you don’t need to study; you’re Asian.”

“That deeply offended me,” said Lee, now a junior. “It stuck with me for a while.”

The assumption that Lee’s academic success is a product of her race disregards the late nights spent revising her notes or completing practice problems.

“By saying my hard-earned accomplishments happened because I’m Asian reduces me to my race,” Lee said. “I’m proud to be Asian and proud to show it, but I should be able to distinguish myself as an individual, too.”

Some students feel that they must conform to racial stereotypes in order to be considered part of their ethnic group. Lauren Campbell has noticed that many classmates think she solely cares about academics and studying. When she admitted to a classmate that she was not going to study for a Spanish test until the night before, he said, “Wow, so you’re a bad Asian.”

“What does that even mean?” Campbell said.

Senior Gabe de la Cruz, who is taking Multivariable Calculus and Partial Differential Equations, has experienced this assumption most often in math classes, but he seldom sees it applied to “brilliant” classmates who are not of Asian descent.

In his experience, the stereotypes that Asian American students are academically high-performing and quiet often come in tandem, so he wonders if he is truly reserved or if such characterizations are racially motivated.

“I don’t think the two are separable,” de la Cruz said.

This story was originally published on The Review on January 12, 2022.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)