Overview

School boards have become the new political battle field, with parents and educators arguing over hot-button topics. This new political landscape has in part come from the realization of the power of education and differing opinions on what children should be taught. From critical race theory to COVID-19, it seems as though topics are becoming increasingly polarizing and anything can be deemed controversial. Amid this increasing division, Jesuit teachers continue to discuss controversial topics in the classroom. But the question remains: why is teaching controversial subjects so important and how does it truly fit into the Jesuit mission?

Civil Rights in America

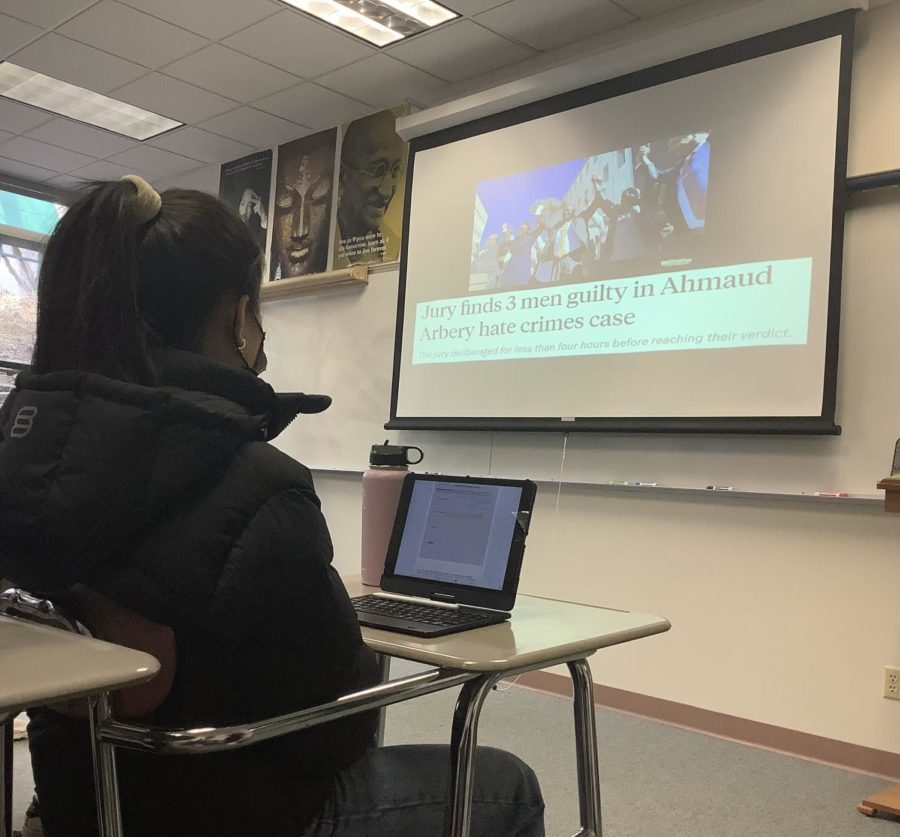

One course in which controversial topics are discussed is Civil Rights in America, a brand new senior class. Civil rights in America “examines the struggle to fulfill founding principles of freedom and equality… providing students with a historical, political, and economic understanding of the struggle to create a ‘more perfect union for all’,” according to Jesuit’s course catalog.

Civil Rights in America teacher, Mark Flamoe, further elaborates on what prompted him and other Jesuit faculty members to create the course.

“This course came partly as a response to the conversations sparked in the last few years about race specifically,” Flamoe said. “People tend to have their own definitions about what freedom, rights, and equality are that don’t necessarily match up with the purpose and intentions of the Constitution.”

In the Civil Rights in America course, students are provided with common definitions, rooted in historical cases, bills, and context to ensure that students are not stripping these ideas from their proper context. Rooting these discussions in historical context helps Flamoe promote productive and respectful debate.

Another way Flamoe cultivates respectful conversation is through highlighting “good faith arguments,” an understanding that most arguments come from a place of good intentions.

“When engaging in any political debate or dialogue, it is important to assume that your opponent has good intentions and that the argument that they are making has good motivations,” Flamoe said.

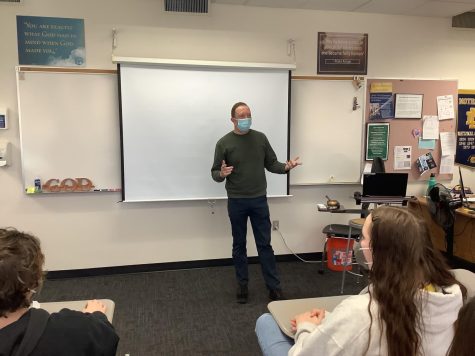

Peace and Justice and Catholic Social Teaching

Matthew Schulte, a Jesuit theology teacher, similarly navigates potential controversy in Peace and Justice class. Peace and Justice is a required theology course for juniors and seniors, designed to be taken after completing the junior-senior year service project. Through examining issues such as poverty, discrimination, homelessness, pacifism, and more, Peace and Justice helps students consider the unjust aspects of cultural and social structures after witnessing them first-hand during their service projects.

“The thought is that Peace and Justice is a place where students can think deeply about things they learned during their service project and hopefully they start to think about questions, asking about marginalization and poverty,” Schulte said.

Junior Brynn Ensminger saw this purpose being fulfilled during her time taking the class, with Peace and Justice providing her with an educational way to reflect on her service and place within society.

“The biggest thing I took away from [Peace and Justice] was the importance to educate myself and have some self-recognition that I have certain biases that I didn’t know I have,” Ensminger said.

Schulte admits that one challenge of navigating these complex issues is finding the balance between pushing his students to be challenged while ensuring that he maintains a learning environment in which students feel comfortable sharing their beliefs.

“There’s this space of healthy discomfort, it should never feel unsafe, but too much comfort is also a problem,” Schulte said. “So there is this zone, the zone of proximal development, where it’s just uncomfortable enough to grow.”

Another challenge posed to teachers discussing controversial content is the question of impartiality. This issue was made even more complex for Schulte who had to balance remaining impartial, so as to not ostracize students with differing opinions or imprint his own viewpoints, with sharing his own personal reflections, a core aspect of the class.

“The tricky part about being impartial is in a way I should be impartial, but the Catholic social teachings and the call of Christ are not impartial, they have a call,” Schulte said. “So, that is a big tension in the class. As a teacher, you must check yourself often and think about the message that’s coming across.”

One way Schulte works to alleviate these challenges is through rooting conversations in Catholic social teachings to dispel tension.

“You want to respect everyone’s perspectives and ideas without shutting them down,” Schulte said. “At the same time, it’s not a debate class or focused on trying to argue one’s point. When it comes to things like the Catholic social teachings, it is not debatable at this school.”

Flamoe similarly acknowledges that the discussions taking place in his class must also be related to the church’s stance and Catholic social teaching. However, he notes that including the Catholic perspective has not been a barrier that limits student discussion, as Catholic values include questioning and seeking truth.

“One of the things that the Jesuits believe is that truth comes through exploration, both through transcendence and experience with God, but also through reason and dialogue,” Flamoe said. “They want students to be able to think and not just be told what to think.”

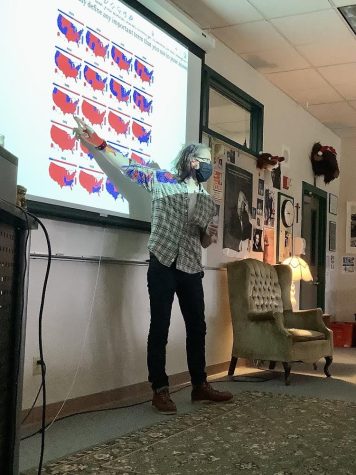

AP US Government and Politics

Another course that discusses controversial topics–AP US Government and Politics–is a senior level history class that “utilizes the analysis of US foundational documents, Supreme Court decisions, and other texts and visuals to gain an understanding of the relationships and interactions between political institutions and behavior,” according to Jesuit’s course catalog.

The goal of AP US Government and Politics is not only to prepare students for the AP test in May, but also to prepare students to be active members of society, according to one of the teachers of the course, Amy Contreras.

“[AP Government and Politics] helps students, as they develop into adulthood, determine what role they want to play in society, both with government, but also through how to interact with our communities,” Contreras said. “[It helps them] be able to understand the historical foundations of our country and be able to build upon that and create the world and society that we want to live in.”

Much of the historical foundation provided to students comes from reviewing Supreme Court cases, including Roe v. Wade, ruling on the constitutionality of abortion, and Obergefell v. Hodges, ruling on the constitutionality of states denying same-sex marriage. Both of these cases include a wide-range of opinions and elicit often controversial and divisive responses.

While preparing students to discuss Roe v. Wade, Contreras noted the heightened controversy surrounding the case and made adjustments to express a shift in gravity to her students. Contreras gave students each a note card and asked students to reflect on understandings about abortion and abortion rights that students believed they could all agree on, no matter what their individual opinion might be. Some of these responses included common concern for women’s rights and well-being and care for children and their ability to grow in a safe environment. These common principles helped to ground an increasingly divided and partisan debate in the humanity and core values that connect us all.

“With Roe v. Wade, the note card was a big indication that this is something that was different from previous cases,” Contreras said. “Additionally, I indicate the gravity of the case with the language I use. I try to tell students that we come from different experiences and by sharing them, we can reiterate the values we have and respect we have for each other and highlight what unites us.”

Contreras explained how these core values connect to the Jesuit principles and values.

“We have an agreed-upon understanding of what we are all connected to…not only in terms of our government principles but also our values: our Catholic values, our values of Jesuit that we are all connected to in some way as members of a Jesuit community,” Contreras said. “This affects not only how we personally view the issues but also how we respond to and interact with each other.”

Highlighting the shared values of the Jesuit community is just one of the tools Contreras utilizes to create a space that cultivates productive, respectful debate in which students are comfortable sharing their political beliefs. In addition to anchoring the discussion in shared beliefs, she also anchors the class in the course’s required terms and cases, providing students with common definitions and understandings they can reference during debates.

“You have to base what you’re saying on facts, evidence, and foundational principles, and have an agreed understanding of what we’re all connected to,” Contreras said.

Contreras also notes that she is teaching this class to seniors who have spent time experiencing the Jesuit community. This experience of community also improves the discussion.

“I think that it really helps that there is already a community established at Jesuit,” Contreras said. “I think it also helps that this is their senior year so students have gotten to know one another.”

Contreras still stresses that while the preexisting Jesuit community acts as a foundation for student discussion, the class encourages students to do further work in order to properly create an environment in which these controversial subjects can be discussed.

“Because we do explicitly talk about very controversial issues, we still need to develop a rapport, which is something that happens over time,” Contreras said. “It’s not something that can be fabricated in a disingenuous way. You accomplish it by engaging in smaller conversations along the way.”

Mrs. Contreras notes that building this foundational class community takes patience, and at times, the class had attempted to discuss subjects they were not ready for. This was experienced for one instance in particular, while discussing current events and the Kyle Rittenhouse case.

“The Kyle Rittenhouse discussion went further than I had expected so I felt like we had to pull back and recognize that we weren’t ready for the discussion,” Contreras said. “I initially wanted students to be able to express their concerns but I felt that it was a situation where we were not ready for that. That was the perfect example of how careful, deliberate, and conscientious we have to be when preparing for these discussions.”

These smaller conversations start with less controversial and personal subjects. Starting with these types of discussions ensures that future discussions will not become heated and overly personal but will instead be focused on developing the foundational skills of discussion and the expectations of respect. These smaller conversations also help students develop their listening skills and become more open-minded.

“Acknowledging and respecting the fact that there are a lot of different ways to look at these issues is really important in order to ensure that students can enter into a conversation where they are not narrowly focused on their own opinion or own political socialization,” Contreras said. “We want them to understand that there are others that they can learn from and who can increase their understanding.”

Patiently and slowly moving into more controversial and potentially divisive topics is all part of the class’s goal: cohesive conversation. This type of cohesive conversation is based not on changing individuals’ minds but finding areas of overlap, where all can connect and agree, building community in the process.

Building Community

Contreras is not the only teacher to note an increased community as a result of her class, Schulte similarly reflects on the importance of community in his class discussions and further the importance of class discussions to community.

“Because we have this community, we can have these conversations with kindness and empathy, but the course is also important to build community, as a large part of this course involves listening to each other without judgment,” Schulte said. “We listen to each other’s stories without judging or labeling them, just hearing them. That is a way to build community and build empathy.”

Sarah D’Souza, a senior in AP Government and Politics, also noted the Jesuit community having a beneficial effect on enabling discussions.

“Throughout our time at Jesuit, we’ve all been in discussions so we know the way you’re supposed to act and respond to people, especially when you disagree,” D’Souza said. “The preexisting community is helpful and the fact that we have all been in a similar environment at school for such a long time helps as well.”

Given the level of partisanship in the current climate, politics, education, and even science has become increasingly polarized. Much of the debate of the outside world is based on ad hominem attacks, divorced from facts and respect. This type of hostile conversation has created gaping divides and fostered an attitude of disrespect that makes bridging that divide seem nearly impossible.

It is this environment of the external world that makes the discussions at Jesuit— and the community it creates—all the more important and impressive. Despite the state of the outside world, Jesuit provides a sanctuary where students can expand their viewpoints and bridge divides between differences. It is for these reasons that teachers at Jesuit view discussing controversial topics as an imperative part of Jesuit’s mission of preparing individuals to be successful in the outside world.

“Our goal is to build the skills— both with the foundational knowledge and the ability to listen, to articulate and back our statements up with evidence—that will foster a likelihood of togetherness and a sense of community,” Contreras said. “Having these skills will help students take the risk to engage rather than to ignore these conversations.”

Ensminger similarly views these conversations as important, especially at a place like Jesuit where many students have privileges.

“At Jesuit, a lot of us have privileges of education or economic security so, it’s important for us to learn what is in society and what other students are going through that we wouldn’t know unless we had these discussions,” Ensminger said.

Reflecting on the importance of discussing controversial subjects, D’Souza notes that discussions are necessary to prepare students for being ready to participate and solve problems.

“If you don’t [discuss and hear differing opinions], you’re stuck in a bubble of your own thoughts and opinions and you don’t see what other people think,” D’Souza said. “And if you can’t understand their perspectives, how will we solve any problems? Being open and having some sort of open attitude towards learning about other people is very much needed in order to go out and solve problems in the world.”

If Jesuit’s goal truly is to create men and women for others—students who are ready to right injustices, create community with others, and actively participate in society—then controversial discussion may be the key tool to fostering community, both in Jesuit and in the world beyond.

This story was originally published on Jesuit Chronicle on March 7, 2022.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)