Sophomore says grief process takes years

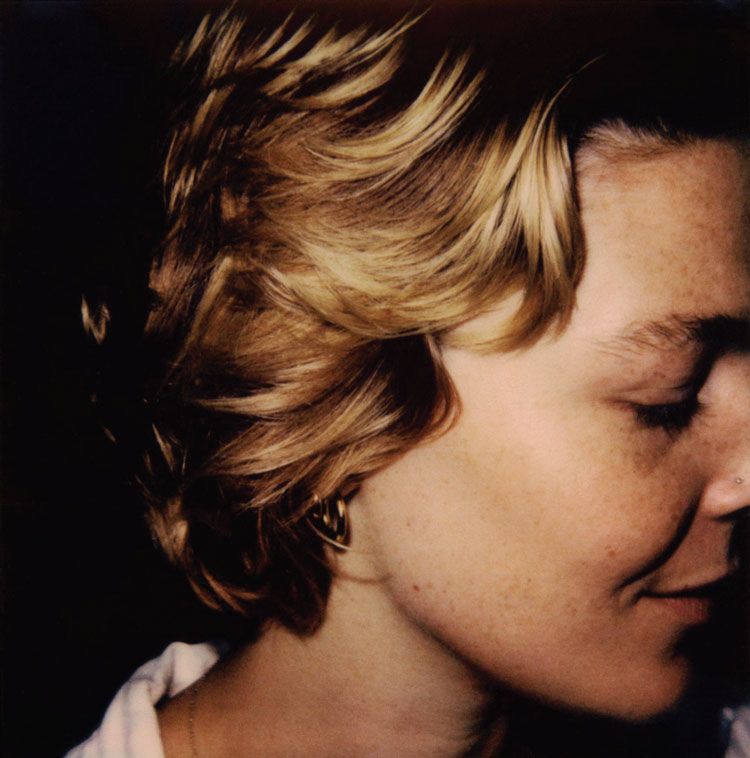

Photo courtesy of the Glidewell family

Kelley Glidewell prioritized her kids, even making homemade Halloween costumes like this one for Reagan (Peter Pan) and for her brother Reece (Peter Pan’s shadow).

March 29, 2022

I was in fourth grade when my mom was diagnosed with stage 4 breast cancer. It was hard to accept that Kelley Glidewell—the loudest parent cheering from the stands, the brightest mom with big earrings and infinity scarves—could be sick. Despite it all, during her chemotherapy my family hosted her shaving party, all of us taking turns shaving off her hair—first with a reverse mohawk and crazy designs, then completely bald—to avoid watching her daily hair loss.

Even after surgery, her remission lasted only a few months. The monster spread to her bones. It couldn’t be cured, but it was treatable.

She continued to be the best mom, making Peter Pan and His Shadow costumes for me and my brother for Halloween and pulling us out of the car to look at Christmas lights.

But normal didn’t last.

The worst came during seventh grade. I was cast as Belle in Beechwood’s production of Beauty and the Beast. Finishing my final rehearsal, I learned my mom had been rushed to the hospital for a tumor clot that had to be drained. My mom, who should have stayed in the hospital, hauled herself to the play’s opening.

A week later, my mom stopped the treatments that were now killing her. With no other options, she said to me, “I am going to die.”

My sister was 7. She cried but mostly because she didn’t understand what was happening. My brother was 15. He was quiet, withdrawn. No tears, just staring.

We took her home. The doctor said she would live a few more weeks—through Christmas. She didn’t.

The day after she died, the empty hospice bed sat in our living room. Even though I was surrounded by family, I never felt so alone. The only person’s hug who could comfort me was gone.

Thoughts of the future overwhelmed me. My first school dance. My high school graduation. My first job. My wedding day. She wouldn’t be there.

Life got hard fast. I was angry. Not just moody, but furious at the world.

Things weren’t great between me and my dad, but it was worse with my brother. We fought daily with screaming and slamming doors. I knew it wasn’t true, but it felt like we truly hated each other. Coping with loss in completely different ways, my brother and I couldn’t understand each other.

I poured myself into school and sports, dealing with my pain with exhaustion. With honors classes, two sports, church, I had no breathing time. Dedicating the things I love to my mom—writing “KG” on every racing swimsuit and writing “KG” on my hand before every running event—I thought it would get easier. It didn’t.

My brother was the exact opposite. He disengaged from the world. He gave up on school, quit his extracurriculars, and just sat in his thoughts.

I saw his pain as laziness. He saw my pain as moving on.

In truth, I was far from moving on. Last year I was diagnosed with clinical depression and an anxiety disorder. These past four months have been the hardest. Instead of relaxing, I spent down time overthinking, especially obsessing about my looks. I stopped eating, lost 10 pounds and lost joy for life. I even tried to overdose on prescription drugs. Yes, drugs.

I know it’s hard for my friends to believe that I nearly killed myself, but it’s true. Even the straight-A, top-notch athlete with the constant smile can hit rock bottom. That’s the power of grief.

I’m doing better now, but it’s not easy. I restarted therapy and rebuilt family relationships. But remember, it was 1,095 days after my mom died when I needed the most help.

I’ve been told that grief takes many forms, but I wasn’t expecting to have such hard relapses into depression three years later. Yet I’ve come to realize that I need to accept grief the same way I accepted my recent foot injury.

I first injured my foot in November during a 1600 time trial. The doctor said to take a couple weeks off, but two weeks later, I felt the same pain. I tried to prioritize rest, waiting another few weeks. However, with just a few jogging steps, the pain in my foot persisted and eventually led to a stress fracture. I was out another six weeks.

Grief is an injury that persists. You make progress and it seems as if everything is fine, but one wrong move and you reinjure yourself. You can get reinjured over and over again, and each time you fall back, recovery takes a bit longer.

As hard as it’s been for me, it can be just as tough watching a friend struggle with grief. It’s hard to understand why one moment your friend is laughing and the next second they go quiet. Or why they can’t get out of bed one day and the next they’re out being social.

You can help in small ways. A simple smile or a “I’m proud of you” can help someone feel loved, known, and wanted when they feel so alone. Even just the presence of a friend can help bring a sense of safety and relief from being with their thoughts and feelings.

The reassurance that they seem to beg for can feel excessive. They also may overreact to minor conflicts. Just remember that loss is traumatic. Be patient.

You can try to put yourself in their shoes, but accept you will never truly understand what it’s like. Loss is complicated. Remember that even if your friend isn’t on crutches or wearing a cast, they still might be broken. Grief has its own timeline for recovery.

This story was originally published on Tribe Tribune on March 17, 2022.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)