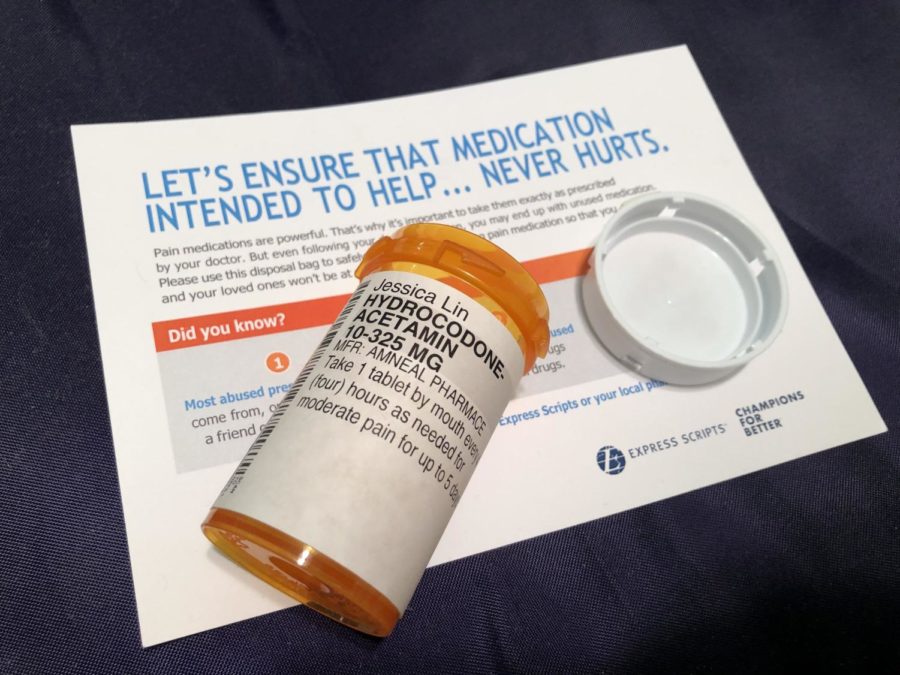

Hydrocodone-acetamin 10-325 mg, Jessica Lin. The pharmacist might as well have handed me a bomb. I had spent my pandemic doing research about prescription opioids and writing a novel about addiction. After combing through personal narratives and scientific journals, I knew that opioids were bad, so why was I getting it prescribed to me after my ACL reconstruction surgery? Though a part of me was curious about the supposed euphoria, it was overshadowed by the fear that lived in the headlines. Would I become another statistic?

Of course, nothing of the sort happened. I took half of my medication before properly disposing of it. The drugs numbed my post-surgical pain, but that was it. Only then did I realize the truth about prescription opioids. Just like with everything else in life, they are not black and white. In fact, the vilification of opioids and the subsequent decrease in prescription can harm patients who legitimately need pain management solutions.

Don’t get me wrong, the opioid epidemic shouldn’t have happened in the first place. Opioids, a class of drug used to treat pain, have been used for hundreds of years, and their addictive nature has always been known. They include codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and morphine, which can be legally prescribed. The illegal drug heroin also falls in this class. In the mid-1850s, doctors noticed Civil War veterans showing signs of addiction to morphine, which was used by doctors on the battlefield. Heroin was created to be a non-addictive alternative, but it didn’t work and was outlawed in 1924. Throughout the 1900s, there were trials that further curbed the prescription of opioids.

However, in 2000, the The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) published the standard that “there is no evidence that addiction is a significant issue when persons are given opioids for pain control.” This was funded by Purdue Pharma, and it began the overprescription of opioids that led to the opioid epidemic we know today. Companies like Purdue Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, and Endo Pharmaceuticals began pushing the opioids that they manufactured, even using paid physician consultants to illustrate the safety of the drugs.

From 2000 to 2012, the consumption of opioids skyrocketed from 46,946 kg to 165,525 kg a year, which led to an increase of overdose-related deaths. After the consequences of opioids began to sweep the nation, in 2007, Purdue Pharma pled guilty to misbranding OxyContin, their prescription opioid. It took until 2017 for the JCAHO to revise the standards for pain treatment.

In recent years, a light has been shined on the epidemic, causing both the medical community and the public to fear the drug. Prescription rates have decreased, with a 40% decline within the past five years. While this is a net good in the sense that it lowers the risk of overdoses, it overlooks the Americans who depend upon prescription opioids to treat their pain. The attempt to overcorrect for the past’s mistakes means that doctors are more reluctant to prescribe opioids to individuals with chronic pain, even sometimes refusing to see them.

Because the science of addiction is complicated, with a whole host of genetic and environmental factors, doctors have attempted to use technology to predict risks. NarxCare is one such algorithm created by Appriss Heath. According to their website, it “helps prescribers and dispensers analyze controlled substance data from prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), assess overdose risk, and manage substance misuse or substance use disorder (SUD)—resulting in more informed prescribing and dispensing decisions”. On paper, this sounds great. Figuring out which individuals have a higher risk of addiction means that opioids could still be prescribed to individuals with lower risks who need the pain management. However, NarxCare is very opaque about its data and the way it determines one’s overdose risk.

Many patients are unaware of NarxCare, even though the score that the algorithm spits out is enough justification for doctors to refuse to see a patient. An individual with a history of long-term opioid prescription may be given a poor score simply because of the doctor’s past prescription. In turn, the doctor may refuse to prescribe opioids because of the score, leaving the patient without options. According to Jennifer D. Oliva, the director of the Center for Health and Pharmaceutical Law at Seton Hall University, NarxCare looks at criminal and sexual trauma records, unfairly affecting people of color and women. This destroys the nuance of medicine.

Even if the prescription is up to doctors, there are still biases at play. Pain is such a subjective measurement, which means that it is up to the doctor’s perceptions of what the patient is telling them. There is evidence that Black and Hispanic people are significantly less likely to be prescribed opioids than surgical procedures when compared to their white counterparts. This may be due to the stereotype that certain races have a higher pain tolerance than others. Additionally, the prescription rates for women and senior citizens are low compared to their level of chronic pain.

Another negative consequence of the reversed pendulum swing of prescription is that prescription opioid rates have also dropped for cancer patients. The World Health Organization recommends opioids for mild to moderate cancer pain, but regardless, the prescription rates have been decreasing. From 2013 to 2017, there has been an approximate 30% decrease in the prescription of hydrocodone-acetaminophen and Oxycontin, two popular opioids, by oncologists. This points to the fact that prescription guidelines for noncancer patients are being incorrectly applied to cancer patients, where pain management could be more important than the possibilities of addiction. According to Dr. Henry Park of the Yale University School of Medicine, “while caution against opioid misuse in cancer survivors is certainly warranted, appropriate pain management is equally as critical to ensure the best quality of life for these patients.”

At the end of the day, one of the biggest issues with prescription opioids is that there aren’t many better alternatives. While it’s true that long-term prescription opioid use has not been convincingly proven to be beneficial for chronic pain, the frenzy of overprescription left patients with a taste of something that seems to work for them. Living with pain everyday takes a hard toll on the soul, which can trigger mental stress, anxiety, and depression. It’s understandable that individuals with chronic pain would take anything that gets them closer to a pain-free life. Nondrug alternatives like massage, acupuncture, and physical therapy are certainly options, but they tend to be more expensive and require long referral wait times. If patients benefit from these alternatives, they should use them, but the right treatment plan should be individualized and take the patient’s specific needs into account.

Prescription opioids are not the best form of pain management, but in some cases, they are the only form that works. In this imperfect world, we must rely on imperfect solutions. Until better methods are developed, prescription opioids allow some individuals to live without pain. Of course, there should still be caution when prescribing opioids, but healthcare should never become black and white. Every individual is unique, and by over relying on algorithms, medicine will lose the humanity that it is supposed to care for. Innovation is wonderful, but it shouldn’t be the sole factor determining treatment. Doctors should also take care to address their personal biases so that they don’t bleed into their care. Everyone deserves a pain-free life.

This story was originally published on Upstream News on March 9, 2022.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)