Breaking barriers behind bars

How education in and out of the prison system supports societal re-entry

October 24, 2022

Chris Schumacher was sentenced to prison for a minimum of 16 years for a drug-related murder. He spent 17 years in jail, including 10 years at San Quentin State Prison. Schumacher entered prison with only a high school diploma and a penchant for violence. Yet, 17 years after incarceration, Schumacher graduated as the class valedictorian of San Quentin’s college program and used his education to forge new paths for himself and other incarcerated individuals.

Schumacher founded Fitness Monkey, an online life coaching service that empowers addiction recovery through fitness. Schumacher and other previously incarcerated individuals’ stories reveal the complexities of life behind bars. They show how both people currently incarcerated and those released from prison can ease the transition of re-entry and improve the public narratives surrounding imprisoned individuals.

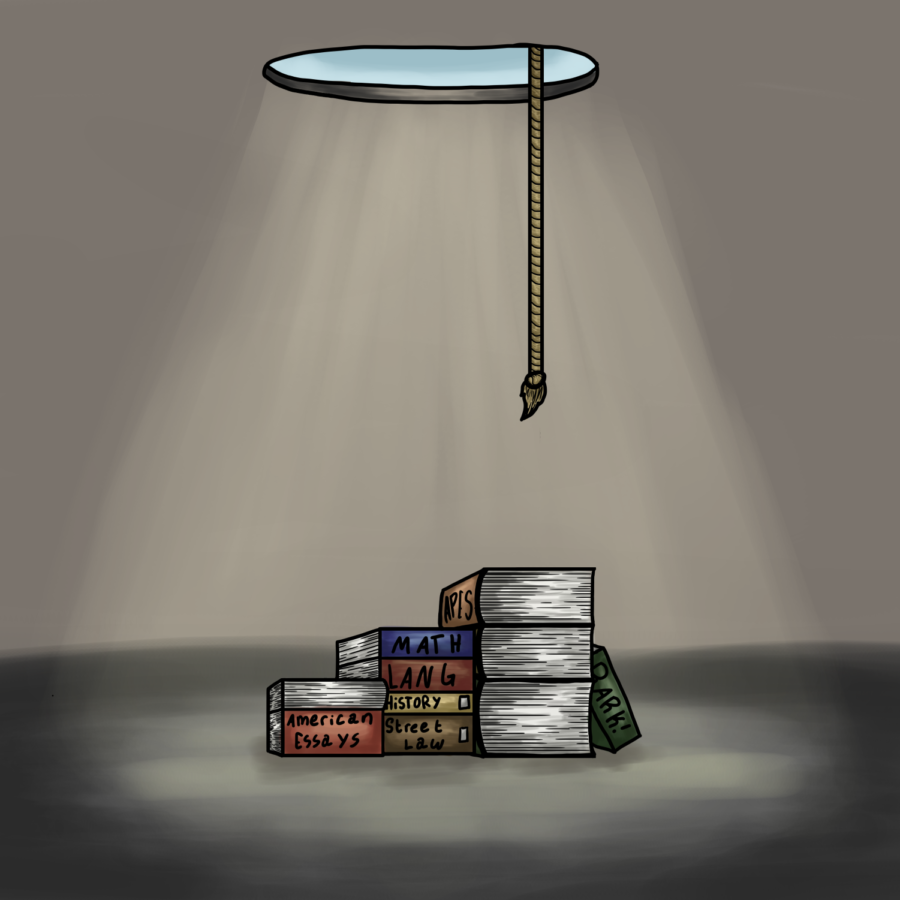

Educational access within the prison system

Some prisons offer educational programs for incarcerated individuals to help them continue their education while imprisoned. One of these programs at San Quentin is Last Mile, an initiative that combines educational resources and vocational training (education relating to employment). In 2012, Schumacher joined Last Mile and combined his knowledge of business and technology, along with inspiration from his own struggles with addiction, to build Fitness Monkey. For Schumacher, both the college program at San Quentin and Last Mile altered his life, introducing numerous opportunities.

“For a while, I had a lot of anger and frustration because the [prison] system didn’t really offer people on the inside a lot of tools and resources for rehabilitation,” Schumacher said. “During my time getting an education, as well as interacting with people from the outside who were willing to invest time and energy into the men at San Quentin, my message went from anger and frustration to gratitude … I had been in a prison where there was a lot of violence, drug and gang activity [compared to] San Quentin, walking around the yard and [seeing] men with calculus books.”

In 2014, Schumacher expanded his Fitness Monkey program online when Last Mile introduced coding and web development courses to prison communities. Schumacher received two and a half years of vocational training and then went to the parole board in 2016. The board said that he had shown steps towards taking accountability for his crime and eventually granted him release.

Corey McNeil was also incarcerated at San Quentin and participated in the same college program as Schumacher, now called the Mount Tamalpais College. Previously, McNeil’s life path led him to drop out of school in sixth grade. Following years of struggle, McNeil entered prison on two life sentences in addition to a 40 year sentence. However, once incarcerated, he turned to the educational resources at San Quentin and was able to learn and generate new opportunities, even from behind bars. McNeil used the General Educational Development (GED) book to study different high school subjects in order to earn his diploma.

“[In prison], I studied the [GED] book like it was my Bible. Religiously, I would wake up in the morning [to read] some, then do some math, all on my own discipline,” McNeil said.

McNeil was recently released from San Quentin in May 2021, with the assistance of these educational resources.

Recidivism

Educational programs similar to the Last Mile directly serve the incarcerated population and can help them atone for and reflect on the mistakes of their pasts. Thus, these programs aim to minimize recidivism — when released prisoners re-offend and are incarcerated again. Recidivism is a significant problem across the current American criminal justice system. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, over two-thirds of prisoners are rearrested during the three-year period of their release. This can be attributed to many variables, including the lack of opportunities for prisoners to make lifestyle changes that would prevent them from committing other offenses.

Rehabilitation within prisons is seen as a critical approach for limiting these recidivism trends. Schumacher observed that education and vocational training can have substantial impacts on the behaviors of incarcerated individuals upon their release.

“Recidivism rate for lifers — the ones who had to do all the work to go home, to learn how to talk about their crime, to understand the victim’s impact, to put the recourse together and get the support to get ready to come home — is below one percent,” Schumacher said.

The influence education can have on individuals’ behavioral patterns can also be seen specifically through Last Mile, where the resources provided helped to bring the recidivism rate of graduates to zero percent, according to Schumacher.

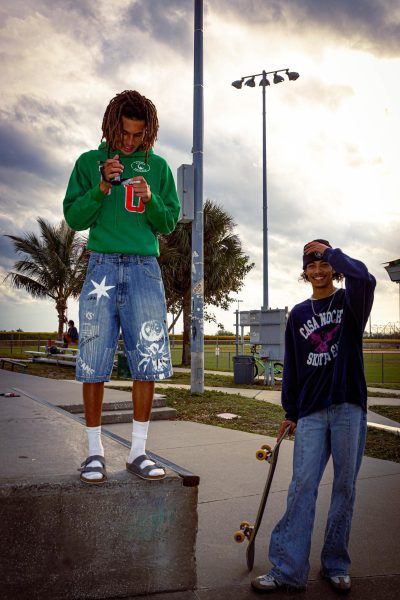

Outreach Organizations

Beyond the work completed within prison walls to develop resources for the incarcerated population, there is a separate struggle for prisoners who re-enter society: grappling with the predispositions held by the general public about released prisoners. Working to adjust attitudes has become a central effort of certain individuals who are developing more genuine narratives of the incarcerated. Humans of San Quentin, an organization created in early 2020 uses storytelling to break down the stereotypes of incarcerated individuals. Diane Kahn, the organization’s founder and mother of a Redwood junior, was inspired by the Humans of New York social media storytelling project, and she decided to develop a similar project surrounding the San Quentin population. In 2017, prior to her idea, Kahn was a teacher on the board at the University of San Francisco (USF). Kahn discovered that USF had a presence in San Quentin and decided to apply to the program to educate the people inside of prison. She was accepted and started assisting men inside of San Quentin to get their GED. Inspired by the people she came in contact with while spending time inside educating, Khan decided to take action.

“It felt [unjust] to me if I didn’t share the stories that I was learning inside with the outside world, simply to educate them, to demystify the people that live right here in our community, who are in prison,” Kahn said.

Humans of San Quentin connects with incarcerated people through word-of-mouth and then mails them a physical packet in which they can write a short piece about themselves and include a photo.

“We really want them to write a first-person narrative, like an experience. We want people outside of prison to be able to identify with them or make a connection. We like them to share just ordinary things that happen in their life and simply tell us about them. Whether it’s in prison, out of prison, in relationships or even just about their breakfast,” Kahn said.

According to Kahn, hearing stories from people on the inside allows others to make connections with them by illustrating the similar emotions, hardships and experiences they hold compared to the general public.

“The [incarcerated] men were emotionally intelligent, they would cry and laugh and be kind of superhuman. Many of them are really in touch with themselves and where they’ve been and could articulate it. When I see these grown men crying and talking about their problems, it shows me that it’s okay to cry. It’s okay to dive deep. It’s okay to be vulnerable,” Kahn said.

Kahn believes that these stories and interactions help break down the imaginary walls between prisoners and the public. Over the past year, Humans of San Quentin has spread from San Quentin to 95 prisons across 35 states. As the organization grows and Kahn builds connections with many more people, she learns of new, fascinating and heartfelt narratives; one, in particular, has stuck with her.

“Dennis tells us the story of one Sunday afternoon. He has a wife, Jasmine, and they have three little girls. [However,] Jasmine and Dennis get into a fight and he ends up killing her this Sunday afternoon,” Kahn said. “Dennis has now been inside San Quentin for 20 some years and in his submissions, he breaks down everything that happened in his life, all the trauma he had, and is now able to look at his relationship with his wife and what has happened with his kids. He takes us on a full journey from what he would’ve done [on that] Sunday afternoon differently, so that incident didn’t [have to] happen.”

Dennis serves as an example of how narrative-based storytelling can change longstanding attitudes toward the incarcerated population. Kahn believes that sharing Dennis’ story allows citizens to humanize their perspectives on incarcerated individuals while allowing the inmates to reflect on their lives and grow.

Though many outreach programs have emerged to help share these prisoner stories, public support for these types of projects is not unanimous. To many people, these incarceration narratives are complex and seen as romanticizing stories that should deserve more scrutiny or skepticism. To others, it might just be a matter of knowledge or an unwillingness to expand one’s mindset.

Sophomore Lindsay Reed admitted that she does not have a wide range of knowledge about what prison is like and who the inmates are.

“To be honest, I don’t think about prison much, but when I do, I think about people that hurt others, whether that be intentional or not,” Reed said.

Reed is not alone in her beliefs towards the incarcerated population at prisons like San Quentin. However, it is these types of attitudes that both educational programs and outreach projects are working to change. Though long-term impacts have yet to be identified, individuals like Schumacher believe that continued progress is possible.

“In prison, a common saying is ‘hurt people, hurt people’ but, on the other hand, I believe that healed people can heal people,” Schumacher said. “The time, investment and energy that you put in people now while they are inside, are the ones that will come back and pay it back as well as pay it forward.”

This idea of uplifting incarcerated people is reinforced by Joe Krauter, a formerly incarcerated individual and editor of Humans of San Quentin. Krauter emphasizes the importance of treating incarcerated individuals as human beings as a way to disrupt predisposed biases.

“People need to see the joy, the life, the love and the humanity [of incarcerated people]. It doesn’t stop, we don’t get to put on pause [in prison]. We’re not frozen in place or laminated, we’re not just thrown away and forgotten,” Krauter said. “Prisons aren’t just a zoo for monsters, they aren’t garbage disposals for the scum of the earth. Rather there are people there that find themselves and then claw their way back out of that pit and come back into society.”

This story was originally published on Redwood Bark on October 1, 2022.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)