The science behind the law

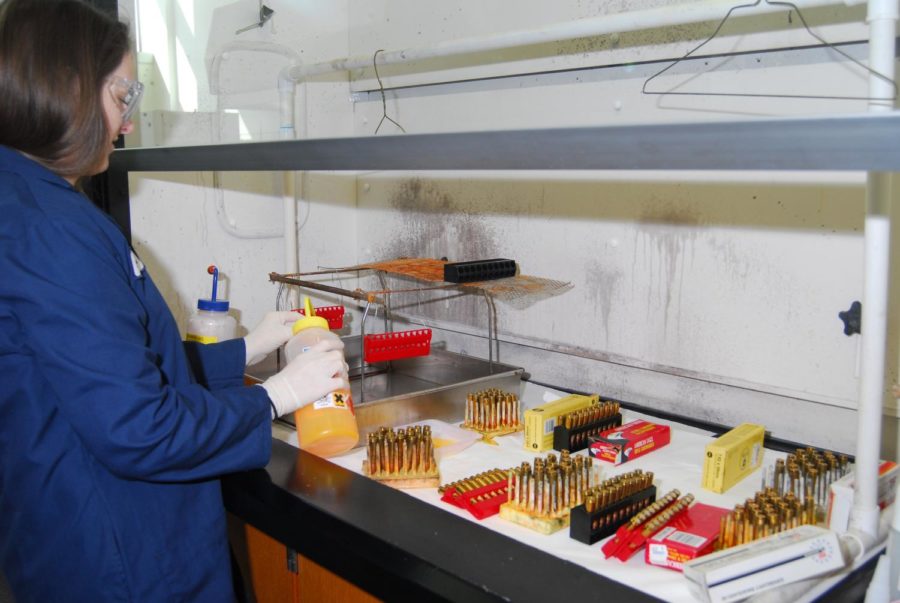

San Mateo County Forensic Laboratory

The job of a criminalist is not as glorified as modern media has portrayed it, but is just as important for solving crimes.

December 7, 2022

Modern dramas such as the NCIS franchise, One Chicago, and Hawaii Five-O glorify the police department and tell thrilling stories about catching criminals. However, behind the high-octane chase scenes and climactic arrests hides a key component in law enforcement, forensic science.

The big screen fails to capture the rich and complex network of scientists, lab technicians, and evidence analysis that enables the Police Department and District Attorneys to do their jobs.

Unveiling the jigsaw puzzle

Forensic scientists, or criminalists, are scientists that apply their expertise and knowledge to law enforcement.

According to the United States Justice Department, the role of a forensic scientist is to “examine and analyze evidence from crime scenes and elsewhere to develop objective findings that can assist in the investigation and prosecution of perpetrators of crime or absolve an innocent person from suspicion.”

A forensic scientist works in conjunction with local police. They provide scientific evidence to assist a case but are not obligated to support a certain narrative.

“We are not here to imprison criminals. We are here to state the facts so that it can lead to a conviction or an exoneration,” said Cindy Anzalone, a forensic scientist and DNA analyst with San Mateo County Forensic Laboratory.

Appropriately punishing a perpetrator is far more complicated than what is shown on television. Forensic scientists must produce hard and indisputable evidence to properly prosecute or forgive someone for a crime. Thus, district attorneys and law enforcement agencies turn to forensic scientists to analyze evidence to create a valid conclusion.

“A forensic scientist is a scientist that works in the realm of law enforcement. We are not cops, we are not detectives, we are scientists. We are in the laboratory 90% of the time, and we all have degrees in physical science, so like biology, molecular biology, or chemistry,” Anzalone said.

However, a case can only proceed to the forensic scientist or the courtroom once it has been reported to and investigated by the local police department.

Depending on the crime, the police department or local sheriff’s office will respond accordingly to secure evidence and the crime scene to conduct their investigation.

“One of the most common crimes in San Mateo County is burglaries, and typically we will respond by collecting fingerprints off doorknobs and maybe evidence from broken glass,” said Antoine Abinader, an officer for San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office and School Resource Officer for Carlmont High School. “When there’s a major crime scene like a homicide, we have a protocol for it. Basically, we will lock down that area, we will gather as much information as we can, from the basic tests we can run and noting down witnesses and who enters and exits the scene.”

Often, the police have to get a search warrant to have access to objects or areas that can be considered private. These objects or areas that are searched are then used as evidence.

“Search warrants are anything from a cell phone to a car to a house. Sometimes you have to write a search warrant to collect somebody’s blood because they’re refusing to do it,” Abinader said. “We need to write a very detailed warrant saying why we want to go to this person’s home or why we want this person’s cell phone and be able to access all their data, and that all gets presented to a judge who then decides whether that’s enough to be that intrusive on a person’s personal space and property.”

Police have the power to access local cameras for recordings during the crime and can interview witnesses with their consent. Once they have exhausted all avenues of investigation, they turn to criminalists, like Anzalone, for further analysis and research.

The job of convicting a criminal falls on the District Attorney’s office. As prosecutors, their job is to gather information regarding a reported crime, using forensic analysis and the police investigation to conclude by filing criminal charges against someone or dismissing the case entirely.

Morris Maya, an assistant district attorney for San Mateo County, oversees most cases of domestic violence, elder abuse, gang, prosecution, homicide, and electronic crimes. Maya and his fellow district attorneys often rely on forensic science to understand a case in its entirety before proceeding.

“District attorneys use forensic evidence, not just to build the cases, but we also use it to understand if we’re right or wrong about who we might suspect is responsible for a crime,” Maya said.

As criminal prosecutors in California, the district attorneys must have “proof beyond reasonable doubt” or almost absolute certainty that a person is guilty.

“We try to make a preliminary assessment as early on as we can because the filing of criminal charges against someone is no small thing. And filing charges can do a lot of damage to someone by just filing a case against them. Even if it gets dismissed soon thereafter, you can imagine the amount of reputation damage that someone might suffer if they get charged with a really horrible crime,” Maya said.

As Maya makes his judgment, he scrutinizes the evidence further by verifying the sources and experts that presented the evidence to him.

“I have to believe that the evidence is sound; I have to believe that the expert who I’m using is qualified; I have to believe that it has been peer-reviewed and, you know, stands the test of scrutiny. Only then will I be able to endorse it as a prosecutor and use it to try to convince the jury,” Maya said.

We don’t file charges unless we feel like we have sufficient evidence to obtain a conviction. It would be irresponsible to file changes if we felt otherwise.

— Morris Maya

Once charges have been filed, Maya and his team of attorneys move to present their case in front of the jury. A 1criminal trial can last for multiple years as new evidence pour in. What’s more, unlike a civil court where only a majority of the jury reaches a settlement, a unanimous verdict is required to get a unanimous verdict of guilty or not guilty.

“As a practical matter, when the jury is unable to reach a unanimous verdict, that is what lawyers refer to as a hung jury, or when a jury has deliberated for a sufficient amount of time, and there is no hope of movement or progression,” Maya said. “When that happens, the judge declares a mistrial or that the case has no resolution. Depending on the split of a jury or the ratio of guilty to not guilty, we can move to retry the case in court or dismiss it.”

Ultimately, the district attorney can continue to retry cases with new evidence and developments. Doing so can present evidence to achieve the correct verdict.

“There’s no benefit in holding the wrong person accountable. And not only is there no benefit, but there’s also real damage being done. When we do that, we harm someone with no culpability; that’s a terrible outcome. So when you understand what a prosecutor does, you can understand why forensic science is a really helpful tool in both incorporating a person who’s involved incriminating, you know them if they’re involved, but also exonerating people who aren’t involved,” Maya said.

Cold cases: how forensic science was used to catch notorious criminals in the past

There have been cases where a criminal can evade the authorities for many years. As they adapt, they become increasingly notorious in the public’s view for their tactics that stun forensic scientists.

“Criminals are adapting all the time. For example, if you look at the narcotics world the chemists that are out there are always reformulating the different drugs. But as we get more cases with these new narcotics, we can start developing better ways to identify it, closing the gap between us for the time being,” Anzalone said.

In the past, scientists gathered evidence in manners that were befitting the period. Often samples were contaminated because the first responders were unaware of contamination or the use of samples for DNA as they had not been discovered. However, as science develops, forensic scientists can revisit cases left unsolved with new techniques, technology, and ideas to discern a culprit or prosecute a perpetrator.

An example was the arrest of the Golden State Killer. A serial killer, rapist, and burglar that had terrorized the bay area from 1974 to 1986. In the specific case of the killer, Joseph James DeAngelo, the killer had served as a police officer who had access to evidence and could easily tamper with the chain of custody or integrity of evidence.

However, with the recent introduction of DNA in forensic science in the past two decades, the case, which had been left “cold” or unsolved for decades, was revisited as evidence and analyzed for samples of DNA.

According to the Orange County District Attorney’s office. DeAngelo was, “identified through Investigative Genetic Genealogy (IGG) in 2018, more than three decades after he raped and murdered his last victim in 1986.”

IGG is the process of matching a DNA sample of a perpetrator to a known relative through the Combined DNA Index System or CODIS. DeAngelo was identified by matching a sample of his DNA to the DNA of a relative nearby and through the process of elimination along his family tree, was eventually arrested and prosecuted.

DeAngelo is now serving a life sentence without chance of parole for 13 counts of first-degree murder, and another 13 counts of kidnapping to commit robbery. Another eight years were added for illegally modifying a weapon according to the Orange County District Attorney’s office.

The case itself would have been left unsolved if not for the efforts of the late local author, Michelle McNamara, who brought the issue to light in her best-selling book, “I’ll be Gone in the Dark” detailing her search for DeAngelo until her death in 2016.

Not only does forensic science assist local cases, but also national ones.

A man that baffled the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the American public was Ted Kaczynski. Nicknamed the Unabomber, Kaczynski mailed bombs for 20 years to selected victims while living alone in the woods of Montana. Through his bombings, he was able to kill three people and injure 23 others while inciting national fear over what he could bomb next.

According to the FBI, Kaczynski was a genius that sidestepped a full-time team of 150 investigators and forensic scientists. They attempted to find any possible piece of forensic evidence that scientists could use against Kaczynski. Still, they came up short because he made the bombs himself and did everything possible to prevent the forensic scientists from giving clues.

“It’s quite interesting that they were able to track a guy whose main communication with the world was quite untraceable, so to speak because he mainly sent explosives and other incendiaries to various educational institutions and instead of something like leaving notes,” said junior Pranav Kamat.

In 1995, the FBI gained a big clue as Kaczynski published his manifesto ‘Industrial Society and its Future.’ Kaczynski’s brother, David, identified that the writing was similar to Ted’s. Linguistic analysts were then able to locate Kaczynski and arrest him by tying the manifesto to letters Kaczynski had previously written to his brother David, allowing them to gain a search warrant on the house.

“I think the fact that they could track him through [linguistics] is quite amazing. That really is a testament to how informative and helpful forensic sciences are in a world where it’s becoming increasingly hard to keep track of things,” Kamat said.

The one constant between the two cases was forensic science. A law enforcement agency’s size, scale, or funding eventually must rely on its scientists to allow them to carry out their arrests. Students such as Kamat, who read about famous cases, are interested in the sciences centered around forensic science.

“I feel like it’s really interesting how they take biology and chemistry and apply it to something that could possibly bring justice to a case. Because I take a little bit of interest in biology and chemistry myself, I find it pretty interesting how they apply the methods which they use, and you know, just the overall for lack of better word, ingenuity,” Kamat said.

‘It’s simple science’

Forensic science covers the use of a variety of scientific methods or disciplines to assist law enforcement in solving crimes.

However, this only scratches the industry’s surface, as the amount of knowledge and specialization goes beyond a corkboard and red yarn. In reality, the title of a forensic scientist is an umbrella term. Each scientist has their domain and works in their own part of the laboratory. Much like engineering, the field is split into many different disciplines, with other counties and laboratories interchanging disciplines based on equipment and necessity.

Within the San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office, the forensic laboratory consists of toxicology, DNA and biology, firearms, narcotics, and fingerprint specialists. Each department works together to use the evidence gathered to determine the immediate information about a crime, how a criminal committed a crime, who was involved, and what happened.

“For a portion of the time, we respond to crime scenes if they need any help processing evidence or collecting evidence, and our job is to be a non-biased scientist whose job is to help connect the crime to certain people,” Anzalone said.

When analyzing evidence, Anzalone and her team use various techniques, equipment, and resources to get accurate information. Forensic science lacks specialized equipment as the field is a mixture of multiple different scientific specializations.

“Many of the tools that we use most of them are found in different professions. All of the test equipment that we use is also used in biotech or hospitals, but because we are forensic scientists we just use them for different purposes,” Anzalone said.

For example, the San Mateo County Forensic Laboratory has recently adopted a new piece of equipment to better record a crime scene and to make crime scene processing much more efficient.

“We have the Leica RTC360 3D Laser Scanner. It’s like a laser that collects data points. So we can show people what we saw. Instead of memorizing the exact measurements of where and what we saw at the crime scene, it creates data points in a 3D visualization of the scene and displays the different evidence items so a jury or other appropriate audience can see for themselves what happened,” Anzalone said.

Additionally, forensic scientists can reuse other scientific resources to gather data. One of those resources is dental stone, a part of an orthodontist’s toolbox for molding braces.

“For instance, if we look at a shoe print in the dirt, we pour dental stone into the depression to capture all the markings of the shoe print and patterns in the dirt,” Anzalone said.

The chain of custody is one of the more critical procedures to ensure evidence is not altered. People need to document where the evidence goes to make sure someone does not disrupt the purity of the evidence.

“A key part of our process is chain of custody. We have to be able to track where a piece of evidence went to be stored, analyzed, or used in court. Without it, the integrity of our evidence is ruined,” Anzalone said.

A forensic scientist must be deliberate, thorough and precise when analyzing evidence because lives and reputations are at stakes.

“Before we even enter the crime scene we need to pass competency training. We have to be careful with contamination because if we contaminate evidence, things can go wrong with DNA testing or other analysis so we have to stay observant and careful so that we can have the best evidence at the end of the day,” Anzalone said.

Ultimately, a forensic scientist’s goal is to present comprehensive and credible evidence to be accepted by the jury. However, as science develops, so do the criminals. The race between criminals and the law has become increasingly tight as the internet and access to online resources are evolving by the minute.

The ability to enforce the law eventually falls onto the capabilities of a criminalist to not only analyze evidence but also to innovate and adapt to match or surpass criminals for lawyers and police to enact justice.

“There’s a sort of arms race of criminology and the criminals themselves trying to evade the advances in forensic science and that there are lots of scientific advances that are going to come out of this,” Kamat said. “In general, it’s always been kind of equal, and I feel it will stay that way for the most part. So it’s kind of good that, by and large, we can catch criminals. Because of this arms race, there are a lot of scientific developments in biochemistry and other fields of science and technology.”

Forensic scientists are not just scientists but also humans. Many of them have to deal with the stresses of examining sensitive information and can face backlash from many different kinds of people.

Additionally, with the rapidly changing political climate and the recent attitude shift towards the police and law enforcement, further pressure is added on forensic scientists to produce the facts needed to prosecute or exonerate people. This additional pressure has negatively impacted the scientists as the pressure to “get it right” mounts.

“In current times, something like George Floyd has become a rough time for law enforcement because there is so much negative attention towards us out there, so we’ve learned to be in a lot of personal wellness training. Having a good support network is very important and being able to verbalize what is bothering you,” Anzalone said.

However, Anzalone believes that the negative attention is not to dissuade anyone from becoming a forensic scientist but is an additional factor to account for when considering forensic science as a career choice.

“I like to tell students that might be interested in forensic science to get a degree in science first. Then pursuing forensic science through programs and internships. Getting a science degree keeps your options open. Forensic programs are great but nothing can fully prepare you for the job because of the nature of crime as a whole. So keep your options open in case you find it’s not for you,” Anzalone said.

This story was originally published on Scot Scoop News on December 1, 2022.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)