“We have the right to read”

Srihari Yechangunja

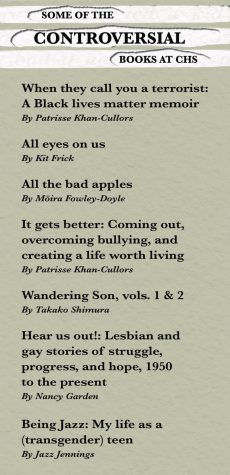

In 2021, Texas state representative Matt Krause drafted a list of potentially controversial books that he suggested be banned from libraries across the state, some of which are available to read in the Coppell High School library. Krause created this list as an auxiliary to House Bill 3979, which banned curriculum that discusses any topics of discomfort, including critical race theory.

January 5, 2023

“Why are we worried a kid’s going to read something and form an opinion that people are bad if he’s around people who are good?”

Coppell High School Principal Laura Springer’s question comes after a series of raucous debates. NBC News reports that the debates argue whether books dealing with controversial topics of race, sexuality and gender identity should be banned from school libraries and classrooms. Texas is no exception to the fiery storm of controversy. From Frisco ISD to San Antonio ISD to Katy ISD, school districts have had books pulled from their libraries due to concerns about their content and appropriateness.

A school book ban, as defined by PEN America, is “any action taken against a book based on its content and as a result of parent or community challenges, administrative decisions or in response to direct or threatened action by lawmakers or other governmental officials, that leads to a previously accessible book being either completely removed from availability to students, or where access to a book is restricted or diminished.”

PEN America found that from July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022, 1,648 unique books were banned in school libraries across the country. Texas has the highest number of bans in the nation with 801 titles banned across 22 school districts and was the only state to have banned more than 751 books. The state targeted titles regarding race, racism, abortion and LGBTQ+ representation and issues.

According to PEN America, 41 percent of the books banned explicitly address LGBTQ+ themes or have protagonists or prominent secondary characters who are LGBTQ+, 40 percent contain protagonists or prominent secondary characters of color, 21 percent directly address issues of race and racism and 22 percent contain sexual content.

An October analysis by The Dallas Morning News found that 97 of the first 100 titles were written by people of color, women or LGBTQ+ authors.

But it doesn’t end there.

In October 2021, state representative Matt Krause issued a letter to school districts with a list of 850 books and urged district officials to investigate if any books on the list were present in school libraries and classrooms. The titles on the list dealt with racism and sexuality that might, according to Krause’s letter, “make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex.”

In fact, PEN America estimates that 40 percent of bans are connected to either proposed or enacted legislation to political pressure exerted by state officials or elected lawmakers to restrict the teaching or presence of certain books or concepts.

The increasingly prevalent reason to ban these books? State bans against critical race theory.

Critical race theory is the idea that race is a social construct and that racism is embedded in legal systems and policies rather than solely being the product of individual bias and/or prejudices.

The basic ideals of CRT emerged in the late 1970s and early 1980s from legal scholars Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw and Richard Delgado among others.

An example of this can be seen in the 1930s when government officials created lines around areas that were deemed as poor financial risks, often due to the racial composition of the inhabitants in those areas. Banks then refused to offer mortgages to Black people who lived in those areas.

Texas signed House Bill 3979 on June 15, 2021. Representative Steve Toth proposed the legislation which, according to the Texas Tribune, says that a teacher cannot “‘require or make part of a course’ or include the ideas that ‘one race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex’ or that someone is ‘inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive’ based on their race or sex.”

Governor Greg Abbott said more needed to be done to “abolish” the teachings of critical race theory in schools and lawmakers set out to create a more stringent bill. The outcome: Senate Bill 3.

Under this bill, a “teacher may not be compelled to discuss a widely debated and currently controversial issue of public policy or social affairs.” Despite the bill not explicitly defining what a controversial issue is, if a teacher does teach this content, they are required to “explore that topic objectively and in a manner free from political bias.”

Additionally, one teacher and one campus administrator at each school district across the state are required to attend a civics training program that teaches educators how the subjects of race and racism should be instructed in Texas schools. Teachers are prohibited from teaching certain topics regarding race and sex and are prohibited from giving any form of academic credit for advocacy work.

Krause’s list of 850 books was intended to determine whether the aforementioned books were being used in public schools and if they potentially came into conflict with Texas’ new anti-CRT laws. According to the Villanova Law Review, Texas legislators and school boards are recommending books and curriculum that “prevents students from reading about CRT and other topics.”

Last year, Texas banned more books from school libraries than any other state. However, CHS has not experienced an instance where a parent has decided to challenge a book at the library.

“As a librarian, as an American, we have First Amendment rights,” CHS librarian Trisha Goins said. “We have the right to read. And there is a reader for every book. And there’s a book for every reader. Our policy for our district is that you are deciding you want to challenge a book, you’re challenging that book for your and your student only. In all my years of being here, that has not happened at our high school.”

When selecting books for the library, Goins is meticulous, conducting research and consulting reviews from other librarians. She ensures that each book will be appropriate for grade levels, generate interest and allow for diversity through literature.

“We want to represent everyone that might be a reader here at our school,” CHS librarian Alicia Grijalva said. “We’re selecting books that are for lots of different readers. Not every book is for every student, but we want to have them available. It would hurt a student if we’re censoring the book they are looking for.”

Every year, Goins makes it a point to celebrate Banned Books Week at the CHS Library which took place from Sept. 18-24. This event, coordinated by the American Library Association since 1982, celebrates the freedom to read and spotlights attempts to censor literature in libraries. The week celebrates and brings together librarians, publishers, booksellers and readers to support freedom in reading.

The idea behind this year’s theme was a metaphor connecting reading to an uncaged bird. When one is able to read, they can see so much more color. Goins invited CHS students to the library to create their own birds to add to the public display. Currently, the display advertises books in the CHS Library that others throughout the United States have challenged.

“I think that censorship ends up hurting individual students. I do believe strongly that not every book is for every person,” Goins said. “We are a place of learning, that’s the whole purpose of being at a school. There are certain things that you must learn in each one of your classes, and a library is a place of choice. Whether it’s realistic fiction, or historical fiction, you have learned so much more through a story. When you can learn something about someone else, you are building compassion and empathy. Aren’t we trying to build a world where we have more compassion and empathy for others?”

“Or at least some of us are.”

According to CISD Board of Trustees President David Caviness, neighboring school district Keller ISD voted to ban books about gender identity on Nov. 14.

“From an administrative standpoint, there’s definitely been a heightened awareness of books that are being used not only in the library, but in the class,” Caviness said. “I credit [CISD Superintendent] Dr. Brad Hunt and his team for being very vigilant and aware of what books and what texts are being used within our different schools. I think that our campus level administration, as well as central admin have been very good at being responsive to parent [and] community concerns when there’s been questions about any particular book, but we have not, since I’ve been on the board, had it rise to a board level that we’ve had to specifically ban any certain text or book.”

Even with the proposed banning of these books at the state level, students have been able to discuss topics that legislation has tried to veer away from.

At CHS, for one, students are allowed equal opportunity to discuss their respective ideas through student-led clubs.

“My deal is, I want every kid in this building to feel loved and accepted for who they are, no matter who they are,” Springer said. “No matter what, they need to have a place. We have so much teen suicide right now and it scares me to death, and a lot of that is because we have not accepted people for who they are. So we’ve had a lot of kids come forward and start clubs, and one is [Gay-Straight Alliance] and it is a great place. People think only gay kids go to GSA, it is a Gay-Straight Alliance and it gets each other’s viewpoints that are different than the world’s viewpoints so that you learn how to live next door to somebody and not think they are a monster because that’s what you’ve heard all [your] life.”

CHS’s Gay-Straight Alliance works to raise awareness on issues faced by the LGBTQ+ community.

“One of our plans would be to spread the word and inform people,” senior GSA vice president MJ Ortillo said. “During some of our meetings, we have some presentations put on by the officers. Currently, we have resources available to our club members if they need [support]; there are organizations and there are people that they can reach out to and talk to. We are pushing to find people to talk to about experiences and the [generational] differences for [the LGBTQ+ community] to learn about people’s experiences and inform the community and try to teach others.”

CHS students also formed a Black Culture Club this year to discuss racial prejudices members face in their day-to-day lives. The creation of clubs or student-led organizations is available to anyone, regardless of their beliefs. To get the club approved, students must find a sponsor, any CHS staff member, and discuss their club plans with Springer.

“For teenagers, I wanted to make sure there was a place where they could go and talk about acceptance,” Springer said. “It’s very important for me for mental health issues that we offer those things in our building.”

As for topics addressing race, books have opened a segue into learning about history that most might consider ugly.

Just recently, junior Black Culture Club president Sedem Buatsi read The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander for her choice reading during her AP English III class.

“It talks about how the Jim Crow laws still exist and about how the drug war that was enacted by President Nixon was really just a way to mass incarcerate Black people,” Buatsi said. “There were a lot of laws that made prison sentencing super harsh and a lot of people went to prison; the majority of those people were Black. I realized that there are so many Black people in prisons, not because they do anything worse, but because of the way that the law is written, and the way that police officers are already in Black communities more [often/frequently]. And [when] Black people [are] imprisoned, they are being stripped of so many rights. I’m 16 years of age and that’s a major part of our history that I just didn’t know.”

Her insight was a result of CHS AP English III teachers allowing students to choose if they wished to read this book – the same book that Krause proposed to ban in his list of over 850 books.

CISD offering such books and creating an inclusive space to discuss such issues is just another way to promote acceptance between individuals without overstepping CRT legislation.

“All the CRT stuff – we’re so worried that we are going to say we had slaves back in the day – hello, that’s part of our history,” Springer said. “Part of our history is ugly, we don’t want to look at it because we were not good people at times. But we need to make sure that we educate. I honestly believe, we’ve said this over and over again, teach history, or history will repeat again. You don’t have to agree with everyone, but you’ve got to learn to accept – you’ve got to look at all the sides of every kind of issue to be able to do that. It is our job to educate people and to accept everyone no matter what they look like on the outside. I think Martin Luther King Jr. said it best, why are we trying to judge someone based on their skin as opposed to the content of their heart? I truly believe that’s the most important thing. I say the same thing about books.”

This story was originally published on Coppell Student Media on December 22, 2022.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)