Proposition 16, the California ballot measure that would have repealed the ban on affirmative action, didn’t pass. 56.1% of California voters voted no while 43.9% voted yes. We were stunned, expecting an affirmative action proposition to pass in a blue progressive state. But not everyone sees it as such. What went wrong?

For starters, it’s evident that not many voters will take the time to actively do in-depth research for each proposition prior to voting. Prop 16 is written as a measure that “permits government decision-making policies to consider race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in order to address diversity by repealing constitutional provision prohibiting such policies.” On a basic level, it says what the proposition does, however the wording is confusing, especially the addition of “repealing constitutional provision prohibiting such policies.” It seems as if the proposition is going to remove any protections that people of color have, specifically by repealing prop 209.

However, that is misleading, and not enough voters clearly understood what the proposition was saying. Prop 209, passed in 1996, was found to be opposed by 74% of Black voters and 76% of Latino voters, per an exit poll. Meanwhile, only 37% of white voters opposed it. The measure was titled Prohibition Against Discrimination or Preferential. Treatment by State and Other Public Entities. Initiative Constitutional Amendment. On the surface it seems like a good thing, no one gets preferential treatment, we are all equals, and we can move on.

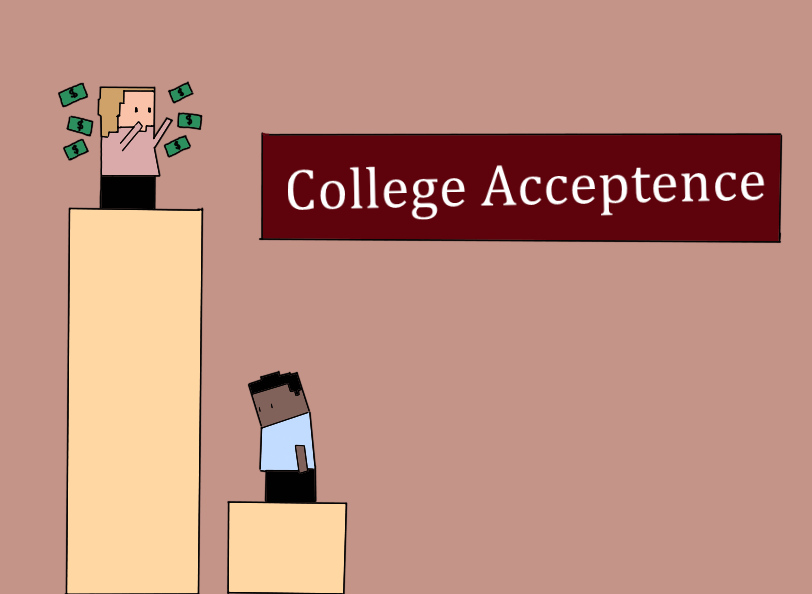

Unfortunately, this is not the world we live in. Systemic injustices are tattooed deep into the soil of the country. Pretending everyone is the equal, on the same playing field, and systemic injustices don’t exist will only exacerbate such problems. Prop 16 was supposed to give those who needed extra support a chance and those who didn’t have a level playing field. As of 2019, 60% of California high school students are Black or Latino, but Black and Latino students only make up 28% of UC freshman admits. Such is with prop 209 in place, illustrating that something new is needed to shift the stage.

Endorsed by Kamala Harris, Dianne Feinstein, Gavin Newsom, the UC student association, the ACLU, and more, prop 16 would have done more than just help minority students get into college. It was supposed to also support women and minority owned businesses; they lost over $1 billion in government contracts over the past 2 decades.

Additionally, reinstating affirmative action does not mean schools will have racial quotas. SFGate managing editor Katie Dowd writes that affirmative action does not mean schools and business will have racial quotas as “courts have repeatedly ruled that quotas are unconstitutional.” Rather, race and gender will be a factor to consider and weigh in certain processes and a factor to not meet a number but to take into account factors that impact someone’s ability to have access to resources, financial/housing inequalities, and barriers to success that exist because of systemic injustices.

According to an Instagram poll of 45 current and former Dougherty students from a variety of cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, 23 voted Yes on 16, 22 voted No, 51% to 49%. Given that Dougherty is a racially/ethnically diverse school, why would this be?

For a multitude of reasons. One is socioeconomic factors. Many students at DV regularly attend test prep centers like Elite and C2, where an SAT prep class starts at least at $2,200. Numerous parents are college-educated, hold a steady job that provides a three-figure salary. Homes in the Gale Ranch and Windermere area are million-dollar homes. Students aren’t regularly concerned if they will be allowed a full-fledged education, rather they are concerned if their grades are good enough.

It’s the perfect “model minority” picture. Because there are so many “model minority” groups, specifically in the Bay Area and in schools with large Asian populations, a proposition that gives “non-model-minority” students an upper hand seems unfair, especially if they attend the same schools that “model minority” students do. After all, both “model minorities” and “non-model minorities” at DV, logistically have access to the same resources, or at least that’s the assumption. However, the need for affirmative action is larger than one specific school and should be debated on.

Megan’s take: an Asian-American student’s perspective

After all, both “model minorities” and “non-model minorities” at DV, logistically have access to the same resources, or at least that’s the assumption. However, the need for affirmative action is larger than one specific school and should be debated on.

I used to lean more against Proposition 16, and browsed through bias sources like College Confidential and read articles about how affirmative action works against Asian Americans, and how there is a “140 point penalty” for being Asian in terms of SAT scores. Because of these biased views and rumors, I was against Proposition 16 in the beginning as an Asian-American senior applying to college, dreading the process of checking the “Asian” box in the demographics section.

This changed when I did my AP Government project on Proposition 16 with Daniela. I forced myself to keep an open mind on the benefits of Proposition 16 and ignored that small nagging voice that told me to argue no.

When I read sources about the impact of Proposition 209 on UC admissions on minorities as well as women and minority owned businesses, I was shocked by the large impacts that banning affirmative action had on these groups. However, no matter what, there was a small part of me that said, what about the impact on Asian Americans? Does this advantage actually have a place in a meritocracy, where everyone should have an equal chance of getting into college?

Based on the research from my government project, I have clear answers to these questions.

For the first question, banning affirmative action may have an opposite effect on Asian Americans that one might think. According to a study done by the National Commission on Asian American and Pacific Islander Research in Education, even if the enrollment to more selective UCs like UC Berkeley went up, the actual admissions rate for Asians went down (most likely due to the overall decline in admissions rate). The study also showed that banning affirmative action has no causal relationship with the increased enrollment numbers. The many opinion articles that I read before had less valid arguments as compared to these studies. I realized that I chose sources that only agreed with my viewpoint, creating this echo chamber that did not allow me to realize the real effects of affirmative action.

For the second question, let’s examine the definition of “meritocracy.” Meritocracy is defined as “a system where people are selected on the basis of their ability.” Can one’s true ability be determined solely on their SAT scores, GPA, selective summer programs, etc? This is only if everyone is on equal footing and has access to the same resources, so the only factor differentiating people is their true ability. But this is not the case. Due to systemic racism, certain groups have socioeconomic disadvantages beyond their control and may not have the ability to join that expensive summer research program or the time to apply for that internship. We need to consider race to gage one’s true ability in the context of one’s circumstances. I am not saying that affirmative action should be permanent, but it is definitely an effective temporary fix, something to help minorities and other disadvantaged groups while we fix K-12 education and have the foundation to establish an actual meritocracy.

The final point I want to make is that thanks to holistic review, considering race is just one factor out of many that can impact one’s admissions decision. To say that your race determined acceptance or denial to a college is a flawed argument, but this mentality is still prevalent in our society. Even I agreed at one point all the way until the beginning of my senior year. I believe that this is the sole reason Prop 16 did not get passed.

The lesson from Prop 16 results? Do your research. Read a good amount of unbiased research studies and articles rather than opinion articles alone before coming to a conclusion on affirmative action. We need to break the misconception about affirmative action before we can enact actual change.

Daniela’s take: a (mixed) Latina student’s perspective

I recognize that this is a controversial take at Dougherty, but I’m personally upset Prop 16 didn’t pass. Here’s where I’m coming from. I’m Latina. I am mixed, my dad is white, my mom is Colombian, but I’m nonetheless, Latina. For years, my stance on affirmative action was conflicted, partially complicated by an ongoing identity crisis of not feeling Latina enough or white enough, not knowing where I fit in, who I’m supposed to be, intersectionality, the list goes on. I realized my experiences didn’t fit the stereotypical image of a Latina student, but honestly most days I forgot I was still partially white because I felt “other.”

What some would call the “Dougherty bubble” influenced my perspective greatly. I’ve never felt extreme academic pressure at home, but many of my peers did. They brought those attitudes to school, always asking others which AP and Honors classes someone is taking, judging people on their grades and by which colleges they are applying to. As a result, I forced a lot of this pressure on myself just to fit in, to be seen as “smart,” many times without even being conscious of it.

The “Dougherty bubble” seemed to collectively agree that “non model-minority” students, such as Black and Hispanic/Latino/a/x students were going to “steal their spots” in college admissions. It’s usually justified by the “we both go to Dougherty, so I don’t see the difference” argument.

From as early as sophomore year, I was told by my Asian-American peers in orchestra, “you’re Latina? You have nothing to worry about, you don’t even have to work hard. Meanwhile, MY race works against me in college admissions. Oh, and you’re the first to go to college in your family? Lucky. ” It felt, for lack of a better word, really crappy, because it almost seemed as if all my hard work inside and outside of school was labeled “diversity admit, Latina” and thrown to the side. I found myself starting to lose touch with my culture, confused about how to fit in culturally, personally, and at school.

I was starting to become someone I didn’t recognize, and being a minority within a minority at Dougherty with the added layer of biraciality made things worse; there is no one like me I can just DM and ask “hey, do you feel this, too?” Do I think it’s dumb that humans need validation? Yes, I hate it. But we all subconsciously seek it and need it to get by. Otherwise, you’re literally trying to be someone you have never seen on campus, on TV, in life. It’s isolating. I started to tell myself “guess they’re right, it doesn’t matter that I have access to more resources, I don’t deserve affirmative action, or any “diversity label.”’

But I realized, I do. And this is why I’m upset that Prop 16 didn’t pass. I constantly invalidated myself because I’m lonely in my identities, eventually realizing that my race, and other things about how I identify, will likely work against me in my life, such as how people treat me, what jobs I’ll be able to get and more. I acknowledge and am grateful for my socioeconomic privilege, along with the privilege of light skin, but I’m also articulating that the college admissions process might be the only time in my life saying “I’m Latina!” helps me achieve something. Anywhere else, it’s a reason why I have to prove myself, why sometimes I’m seen as less, less smart, less capable, someone with the smallest voice in a room with downgraded credibility.

I realize the world is polarized, and I’m not surprised my peers are conflicted on this topic. I also admit that I don’t know everything, I’m still learning. But I’m here to say, Prop 16 was badly needed, and I implore others to do their own research, just like Megan said.

This story was originally published on Wildcat Tribune on December 7, 2020.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)