Drawing the line: “diversity” in animation borders on racism

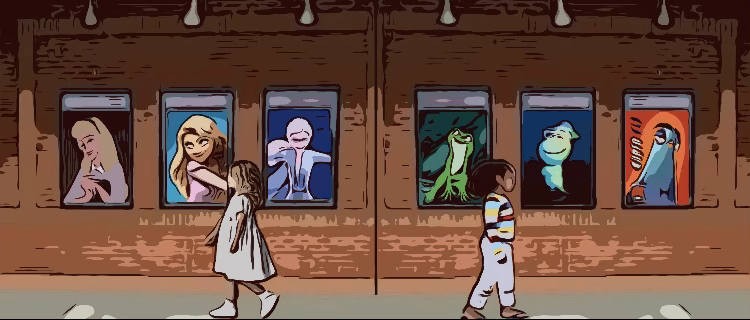

Illustration by Kylie Clifton

We don’t often consider that for many of us, with every step we take, there is someone else walking in a different direction without the same privileges. We can’t erase our privilege, but we can use it for good, and examining diversity in animation is a good place to start.

February 15, 2021

Growing up, nothing was better than an animated classic: a simple film with good morals, fun moments, bright colors, immersive worlds, and characters you could relate to. Wonderful adventures all wrapped up in 90 minutes or less you could watch it again and again.

My internal conflicts growing up couldn’t exactly be solved 90 minutes, and I didn’t have characters I could relate to. The overall purpose of animated films is to entertain and immerse yourself in their storytelling. While I didn’t feel represented, I was certainly immersed, escaping my gender the best I could.

Growing up a little boy who was truly a little girl along, my story was still waiting to be told. I just wasn’t ready to press play. Despite that, I was still privileged to see exactly who I wanted to be regularly represented in film. Everywhere I looked, I saw white and blonde Disney princesses who didn’t look like me, but who felt like who I was supposed to be.

Back then, I didn’t realize that children of color experiencing my same internal conflict didn’t have my same ability to escape my personal struggle. It wasn’t until later in my story that I realized animation is strictly catered to white people.

It was June of 2019, and Pixar announced their upcoming feature films.

As a longtime devotee to animated films, the picture that caught my eye wasn’t Onward, with its promise of a fantasy adventure featuring blue elves and their dead father’s pair of legs. Instead, it was the film that, following twenty-one films with little to no representation, would feature the company’s first ever Black lead: Soul.

Soul was poised to follow the adventures of a Black male musician who was a middle school band director by day and a budding professional jazz musician by night. I was hooked immediately, ecstatic at the announcement, and clicked as swiftly as my fingers could move when the first trailer dropped.

My excitement dwindled when I realized the title Soul wasn’t named after his journey with soul music, but his journey in the afterlife. Viewers see the main character, Joe, thrilled that he got the gig of his dreams, but then the trailer ends with him crossing the street to his demise. It isn’t even a somber moment: his death is the final gag laugh of the trailer. One minute he is living his dream, and then poof, he falls down a sewage manhole.

Afterward, he emerges as a green blob of energy, now a proper Soul on the bridge to the final resting place, dead on arrival right as he was reaching his dreams.

And just like that, what could have been a brilliant chance for Pixar to take a step toward diversity turns into a tale of poorly poetic irony: their first ever Black main character isn’t just killed off at some point in the movie, he meets his demise in the trailer.

Certainly this film was put into production long before the murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and a very long list of many more victims of police brutality and systematic racism, but the weight of this choice by Pixar still remains, no matter how innocuous the intent. They released their first ever feature film featuring a Black main character in 2020, and he’s killed in a laughing moment in the first ten minutes and then spends the rest of the movie not Black, but blue, and then eventually not even in human form, but as a cat.

I was deeply disappointed, because I had seen this all before.

Animation has had a long and poor track record with legitimate visibility for any characters of color. In Disney Animation’s 2009 Princess and the Frog, Princess Tiana’s dreams of opening a restaurant as a Black female business owner in 1920’s New Orleans are sidetracked because she kissed a frog, causing her to spend over half the film as a frog herself. Princess Tiana is also the only of twelve disney princesses to not be born of wealth and royalty. Obviously her storyline revolves her rising above her homelife and reaching her goal of her own restaurant. If she was born into wealth and royalty, it would simply be too easy for her. Although Tiana seems more grounded than the other princesses, it comes at the cost of her having to climb even farther to stand amongst royalty and other princesses born of privilege. Almost indirectly saying Tiana with her melanin and curls wasn’t good enough to be born into royalty. At the time, the film was celebrated for its diversity, but the truth wasn’t that it deserved the accolade because of it’s introduction of the long-awaited Black Disney princess, but rather that representation had been so sparse before that the fact that she only spent 42% of her screen time as a Black woman felt like a victory.

This trend continued with 2019’s Spies in Disguise, 20th Century Fox’s animated film which followed a Black Bond-like character that exudes all things cool until he was transformed into a pigeon early in the film. Initially, this seemed to be a large feat for visibility with an awesome character for children to look up to on all his spy adventures. Only his becoming a pigeon diminished the weight and impact of the film’s Black lead character, especially considering that the white teenage scientist that accidentally turned him into an animal in the first place got far more screen time than the main character of color himself.

I know that visibility is necessary in any film, but especially when it comes to children’s film. These films shape a child’s entire outlook on the world, because they shaped mine. I believed for a long time the best disney princesses were the white and blonde ones, because that was all I saw and all I wanted to be. Unaware that I could look up to any princess of every ethnicity or story. My experience is taken to the next level for children of color. If they only ever see white main characters in every story, film, show, or any form of media, they begin to see themselves apart from the stories broadcasted all around them. This has been a longtime reality, reflected in the unfortunate results of the 1940’s doll experiment, in which Black children in the study chose white dolls over dolls that looked like them, seeing their darker skin color as inferior to that of the white dolls they chose. This same scenario, where Black children are socially conditioned to internalize ideas that they are somehow less valuable, is being played out sixty years later in mainstream media. White or lighter skinned children see themselves projected in every aspect of the world around them, and their future feels boundless as a result because they can see unlimited opportunities for people that look like them. That simply is not the case for Black children, whose cinematic existence is relegated to living as an amphibian, bird, or soul for a vast majority of the film. Indirectly saying that characters that look like them are only interesting if transformed into something that isn’t their melanin.

Soul, for the most part, didn’t fall as hard as it’s predecessors. It has redeeming moments: the film follows Joe’s journey to rediscovering his soul and his dreams of soul music featuring a wide cast of diverse supporting characters that offer heaps of visibility and great storytelling. Pivotal moments featuring Joe’s local barber, his mother’s tailor shop, and auditioning for his dream gig with a famed musician of color Joe looks up to all provide positive representations of Black American culture.

Despite this, the film walks a fine line, particularly late in the film the problems emerge. A desperate Joe ends up accidentally swapping places with another soul (voiced by Tina Fey), leaving her white persona in Joe’s black body and Joe’s black persona in a therapy cat. The “walk in each other’s shoes” is ultimately therapeutic for them both, but the mere idea of a white soul living a day in a Black man’s body just doesn’t sit well with me. The body switch trope is well-established in film, but in this case, it’s repercussions when societal disparity and systematic racism come into play make it not just a fun switcheroo anymore. Although the film is rooted in clear fiction, the idea that they intentionally chose to have a presumably white character walk in a Black man’s shoes without at all demonstrating the difficulties a Black man faces on a daily basis in a systematically racist society seems not just a faux pas, but an act of legitimate ignorance. Soul doesn’t even touch on the social justice issues that Joe would face on a daily basis as a Black man living in America, and it’s disappointing that these nuances are entirely overlooked.

After dissecting these films for all they are, it’s important to know despite the flaws and the potential underlying racism at play, these movies still mean something to people. Even if sparse, they portray some inspiring and wonderful characters of color that deserved far more screen time as themselves, melanin and all. I just hope that going forward, film studios more fully comprehend the importance of diverse storytelling, understanding and accepting the responsibility that comes along with it. I wish I had more diverse stories growing up, I would have known earlier on that role models are not restricted to race. I can’t even comprehend how my life would have been changed if I saw a character with the same gender struggles as me. While seeking to tell more diverse stories, we must remember it is a complete disservice to tell said stories without acknowledging the complexity of their existence. They must be given the prominence and fullness in lead characters that they deserve. Above all else, it is imperative to never forget the following, despite what the films portrayed.

Black women are not frogs.

The death of Black men is never funny.

Black excellence is never too much.

Characters of color don’t need to be transformed to tell captivating stories.

Diverse storytelling can only be told by diverse voices.

This story was originally published on The Northern Light on February 13, 2021.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)