Behavioral screener raises concerns

Anna Rachwalski

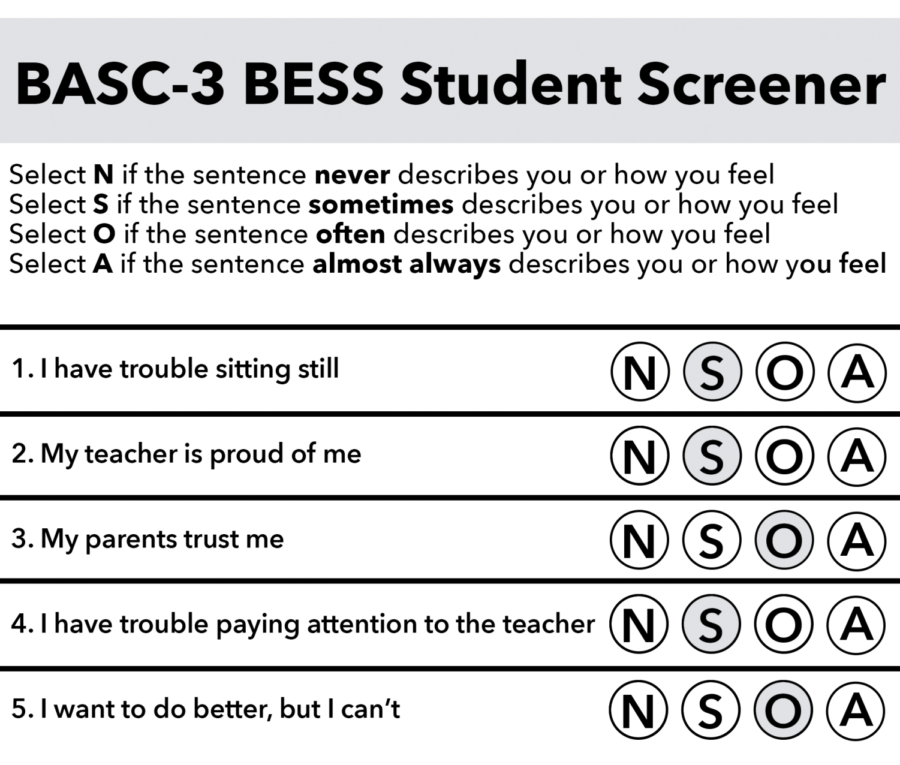

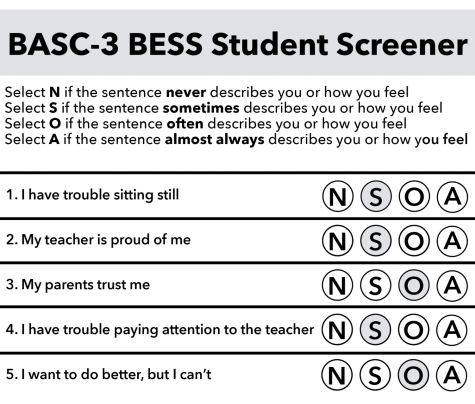

The BASC-3 BESS screener included prompts about student’s behavioral and mental health. The answers above were taken from a publicly available sample report from Pearson, and the formatting was taken from a personal screener report received by a member of the Southerner staff.

December 16, 2021

A behavioral screening, commissioned by Atlanta Public Schools and administered to Midtown students, has prompted privacy concerns.

Many students, parents and teachers said they did not have adequate information before the screener was conducted in the Fall about the process of the screener or how the data would be used. These concerns have become more apparent in the time since the original administration of the screener.

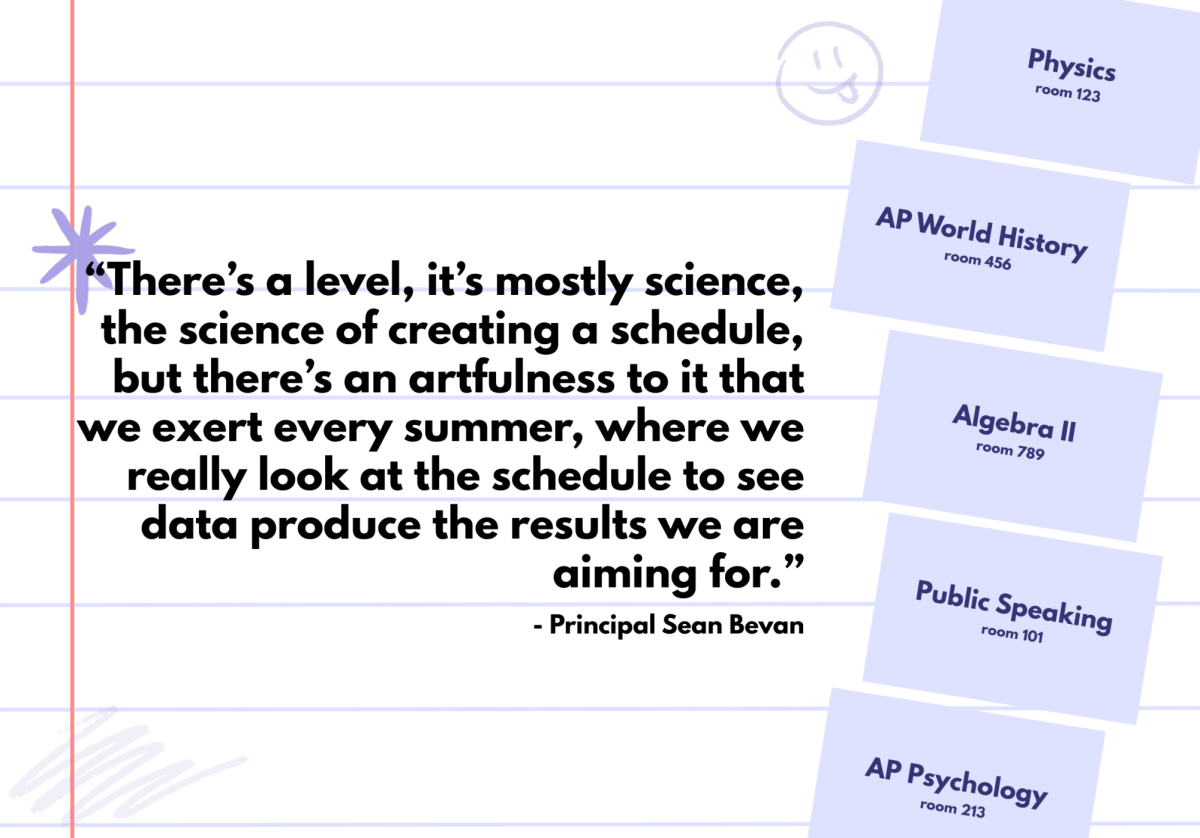

Background on the BASC-3 BESS screener

The screening tool, formally known as BASC-3 BESS (Behavior Screening Scale), is a tool developed by Pearson, a large media company that provides publishing and assessment services to schools and companies. It was distributed once during the fall semester and will be distributed again in the spring semester.

“The assessment consists of a brief rating scale that will be completed by the homeroom or advisement teachers,” according to a letter uploaded to Infinite Campus’s message center before the screener was given. “In addition, students … will be invited to complete a self-rating … parents of students grades Pk-12 will also be invited to complete a brief rating scale about their student(s). Together, this information helps us to understand the needs of all students, and to make effective plans to support those needs at the school, class and individual levels.”

According to APS Student Support Director Dr. Shannon Hervey, the BASC-3 BESS was chosen because of its functionality. Review360, the broader program under which the behavior screening is hosted, offers teachers and administrators digital access to student data.

“[The screening] also has courses that teachers and staff members in schools can take to help them,” Dr. Hervey said. “It also allows our schools to be able to see their risks in a really easy and user-friendly way … to let them know, at a glance, who needs support.”

Concerns about collection of data

Information about the screener was distributed to parents and guardians as part of the district’s communications about the reopening plans, as well as via texts, email notifications giving parents the chance to opt their children out, but there was not much information on what the screener entailed, according to Midtown cluster parent Jennifer Silver.

“I knew the assessment was going to be administered and that it was the universal mental health screener,” Silver said. “That was about it. There wasn’t any discussion about who would receive the data, how it was going to be handled, what it was going to be used for; it was very vague … we were not provided with any information about who the vendor was.”

Silver has a student at Midtown and a student at Howard Middle School. She said her first thought was that the information collected was medically private. As a result, she opted out both of her children. However, her middle school student was still made to take the screener, she said.

“When my student contacted me to tell me that they had to take the test, even though I had opted them out, I contacted the principal at the school immediately because I was very upset,” Silver said. “What I learned is that it was an oversight. I think the teacher that administered the screener did not have the information about the students that opted out until after the screener was already administered.”

Silver was assured that, due to the oversight, the data her student provided would be completely erased and removed from the rest of the data collected.

Teachers also had to fill out a separate screener for each student in the class in which the screener was distributed. Silver said that despite her efforts to stay informed via multiple sources of information, she was not aware that teachers would be doing this for the students who participated.

“My mind is being blown right now in the worst way,” Silver said. “It’s possible it was mentioned … but generally, I’ll find out about things like this … It really depends on the relationship between the teacher and the student, and it seems like it would be difficult for a teacher who teaches hundreds of students to potentially have a depth of information about the mental health status of any one of their students.”

Senior Bella Diallo participated in Midtown’s virtual school last year, but is new to the school and agrees teachers may not be able to accurately assess the mental state of their students, especially given large class sizes. Diallo said she also was not aware her parents and teacher would assess her and thinks that information should have been announced in the classroom before students took the screener.

“[Having our teachers and parents complete a screening for us] is a little more concerning; I had no idea,” Diallo said. “I feel like if they were going to say our teachers were going to fill it out as well as our parents, I feel like they should have … made that more explicit before we took it. Before MAP testing, they have to read a set of instructions — if before this test, they were like ‘just so you guys know, your parents are also going to fill it out’ would be a lot more helpful because it feels kind of sketchy that they didn’t say that.”

Dr. Hervey said information about the screener was widely distributed.

“We’ve been transparent from the very beginning, as to this screener, and that there would be three levels of it,” Dr. Hervey said. “That’s even in the notification of the opt out form that we actually sent home to parents. So, I’m not sure how they may have missed that. We also have a web page on the website.”

Language arts teacher Lisa Willoughby said she went through a 30-minute training before the assessment was distributed but said it was mostly procedural and teachers received minimal information about the rationale behind the screener. Willoughby also expressed concern about the ability for her, as a teacher, to assess the mental health of her students.

“There are some questions that are relatively easy to answer,” Willoughby said. “But, how do I know how they are feeling? It’s hard for me to get a sense of whether or not a student is feeling stressed or anxious. I only see what appearance they project in class, and that could vary wildly.”

The vendor, Pearson, recommended that a teacher knows the student for six weeks before completing the screener for their students. According to Dr. Hervey, if teachers felt they did not know the student well enough to fill out the information, they could opt out of evaluating that student.

“We told them if you feel like you do not know this student, and that could very well be the case, even if the student had been enrolled for six weeks … let’s say for many days due to illness or suspension or whatever the case may be … all they get to do was deselect the student,” Harvey said. “That was made crystal clear from the beginning.”

Concerns about potentially unfair incentives

Principal Dr. Betsy Bockman confirmed that Midtown offered five community service hours for students who took the screener. Some parents were concerned that this was an unfair incentive for taking the screener, for those who wouldn’t have participated otherwise.

“I really don’t like the idea that students were given an incentive or felt maybe pressured to participate when they wouldn’t have otherwise to get five hours of volunteer service hours,” Silver said. “It seems egregious.”

Dr. Hervey said she was not aware of schools offering incentives.

“I have no knowledge of a school offering that kind of an incentive, and I will definitely be following up,” Dr. Hervey said.

In a follow up email, Dr. Hervey said that “student participation in a universal social, emotional, behavior screener is not a permissible community service offering” and that the district was currently revising guidelines for what is considered “acceptable community service.”

Concerns about the use of data

While Diallo respects the intent behind the administration of the BESS, she was not aware before taking the assessment of what would be done with her data and is skeptical of what material change will come from it.

“I don’t necessarily know if they are going to make any changes,” Diallo said. “They haven’t really said what is going to happen if your mental health isn’t very good … it’s just very elusive to me.”

Dr. Hervey emphasized there is not a cookie cutter approach to how the data from the BESS screener would be used. The data can be accessed by employees on the district level and by school teams who can follow up with families based on a student’s results, according to Dr. Hervey.

“The data from the BESS is really just a starting point for a conversation between the school and the student and the parent,” Dr. Hervey said. “What this will do is to prompt our educators to have those conversations with students and parents to be able to confirm and identify the risks, and then to collaboratively come up with a plan for how their student would be best supported.”

According to Dr. Hervey, school counseling departments were provided a “response protocol,” which included meeting with students who had elevated risk and discussing this risk with parents. Schools were given autonomy as to how the screener was administered and the response from schools about their ability to fulfill the expectations set by the district have been mixed.

“The feedback received from schools has varied,” Dr. Hervey said. “Some schools strategically administered the BASC-3 BESS throughout the entire screening window to ensure that student support staff could adequately address the follow-up for students; other schools administered the screener to all students within 1-3 days, and then reviewed the outcome and began their response. This was the first administration of the screener, and schools have learned valuable information that will assist them in pivoting to ensure even greater success with the spring administration.”

Freshman Micah Solomon was asked to meet with a Student Support faculty member as a follow up for his screener results. Solomon said the meeting was “positive” and “helpful” and that said there was always support available if needed.

“They were like, ‘you answered “often” for I worry a lot about what will happen in the future,’” Solomon said. “I just explained it’s like self-consciousness … They were like, ‘alright, yeah, I understand that.”

Dr. Bockman said follow-ups began in mid-October after the screener results were received and that counselors have been meeting with students based on indicated risk but little support has been offered by the district.

“No additional support has been provided by the district to implement this screener initiative,” Dr. Bockman said. “This is another task that has been added to their plates. They are meeting with students on a consistent basis in order of priority — extremely elevated indications first, followed by elevated indications.”

Two Midtown students, who prefer to remain anonymous to protect their privacy, said while they think their answers should have

necessitated a follow up, their counselors have not reached out.

“My counselor has not reached out to me,” Alex Nathaniels* said. “She would have reached out to me if she saw [my results].”

Dr. Bockman also urged students to immediately reach out if they need support.

“As always, screener or not, if students need mental health support, they should never wait — talk to their parents, stop by the counselor or social worker offices,” Dr. Bockman said. “Do not wait if you need help.”

The Midtown counseling department declined to comment.

Concerns about distribution of data

The other major student concern is the data from the BESS screener was sent home with mid-term progress reports. Many students were not aware their parents would receive their results.

health. The answers above were taken from a publicly available sample report from Pearson, and the formatting was taken from a personal screener report received by a member of the Southerner staff. (Anna Rachwalski)

Jessie Davidson* said they would have rather talked to their mom about going back to therapy on their own.

“I did want my mom to know, but definitely not that way,” Davidson said. “I would have rather come to it with her, so she could know exactly what I want her to know. With that, she gets to know everything.”

Dr. Hervey said this information was available.

“Prior to the opening of the fall screener window, school screener ambassadors were advised that the decision had been made to send score reports home,” Dr. Hervey said.” “This was also discussed in the cluster parent meetings that were held during the months of September and October, and posted in the BASC-3 BESS Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) that were posted on the APS website.”

Dr. Bockman also said the whole process was explained to parents.

“As legal guardians of our students, parents have the right to have this information,” Dr. Bockman said. “Parents need to have all information regarding their children. This screener is used to provide information to parents and students so that appropriate action steps can be taken by the family if indicated. The overall health of a child is the responsibility of parents — we want parents to have knowledge of their students’ health. This is information not a diagnosis. We only want to help parents and students make decisions for their family.”

Nathaniel did not know their score report would be sent home until her friend told her that the results of the screener were sent home with progress reports. Nathaniel made sure to intercept it.

“I dug through my mail, and I found it,” Nathaniels said. “If my parents had found that, I would have been so screwed … They should have definitely said something beforehand.”

According to Dr. Hervey, APS believed it was important to share this information with parents to better address “the full spectrum of whole child supports.”

“As the district’s first universal screener for behavior/mental health, APS found it important to share the overall results of the BASC-3 BESS with parents for this initial administration,” Dr. Hervey said. “This decision is not intended to cause harm, but rather to provide parents with additional details regarding their child’s behavioral and emotional strengths and weaknesses, especially in light of the pandemic.”

The screener included questions about how students felt about their home lives and their relationship with their parents. Having parents to see the information first was uncomfortable for some students, Davidson said.

“I know for so many people that’s so awful; I can’t even imagine,” Davidson said. Sam Cloverson,* a current Midtown student’s older sibling, who asked to remain anonymous due to the nature of their job, said they were enraged by the information being sent home without alerting students ahead of time.

“Regardless of what [my sister thought], my initial reaction was totally just based on immediate anger at the situation and just disbelief that this is able to happen,” Cloverson said. “My sister expressed that this was really upsetting, and thankfully, my parents were really respectful about it and didn’t read it without her permission, but I can assume that a lot of parents did read it, regardless of their child’s permission. My sister was obviously worried about other students, as I was, because you never know how parents will react to that situation.”

Cloverson sent an email to Dr. Hervey, who was the contact provided for any questions about the screening.

“As an Atlanta Public Schools alumni, I understand the need for mental health resources for students, guardians and the community … I do not understand why students were not told that their scores would be shared, especially considering many of the questions were about guardians, and you have no idea how parents or guardians may react to positive or negative feedback,” Cloverson wrote in the email. “If I was a student today, I would feel upset and violated.”

In an email back to Cloverson, Dr. Hervey responded, “Thank you for your email.”

“That didn’t really make me feel heard,” Cloverson said. “I don’t think that many people do feel heard when they communicate to APS; so, I wasn’t entirely surprised.”

Students are scheduled to take the screener again in the spring and parents can indicate before the next administration if they want to opt out their student.“I’m not taking it again,” Davidson said. “No way. I’m not taking it again.”

*Alex Nathaniels, Sam Cloverson, and Jessie Davidson are all sources who asked to remain anonymous to protect their privacy.

This story was originally published on The Southerner on December 13, 2021.