In a Dec. 13 email sent to the AISD community, superintendent Stephanie Elizalde announced that AISD would not be switching to a seven-period schedule for the 2022-2023 school year.

“The feedback I and others on my team have received has been clear,” Elizalde said. “You want an eight-period day with block scheduling. And after discussing this with our principals, that’s exactly what we’ve decided to do. For the 2022–23 school year, Austin ISD schools will run an eight-period block schedule as most of our schools do now.”

The email also stated that AISD continues to face fiscal pressures, with a $62-million budget deficit and the inability to tap into any more of its cash reserves. Upon reading the email, many AISD teachers and staff began to question how the district would save money next year, while continuing the more expensive eight-period block schedule.

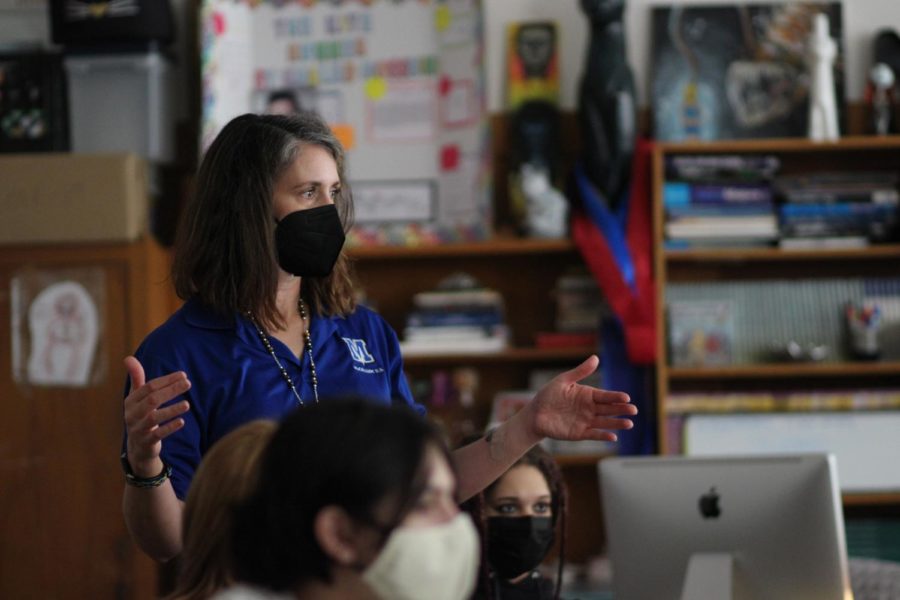

About three weeks later, on Jan. 3 in a McCallum staff meeting, principal Nicole Griffith officially announced that teachers would be teaching seven out of eight periods, with C-days and early releases every Monday.

Butting heads with the budget

Until McCallum receives its official 2022-2023 budget from the district, the school won’t know exactly how many teachers it will be able to employ next year. While the number of support staff, including clerks and assistant principals, is determined by the district, local administration has some discretion in deciding how funds are allocated for teaching.

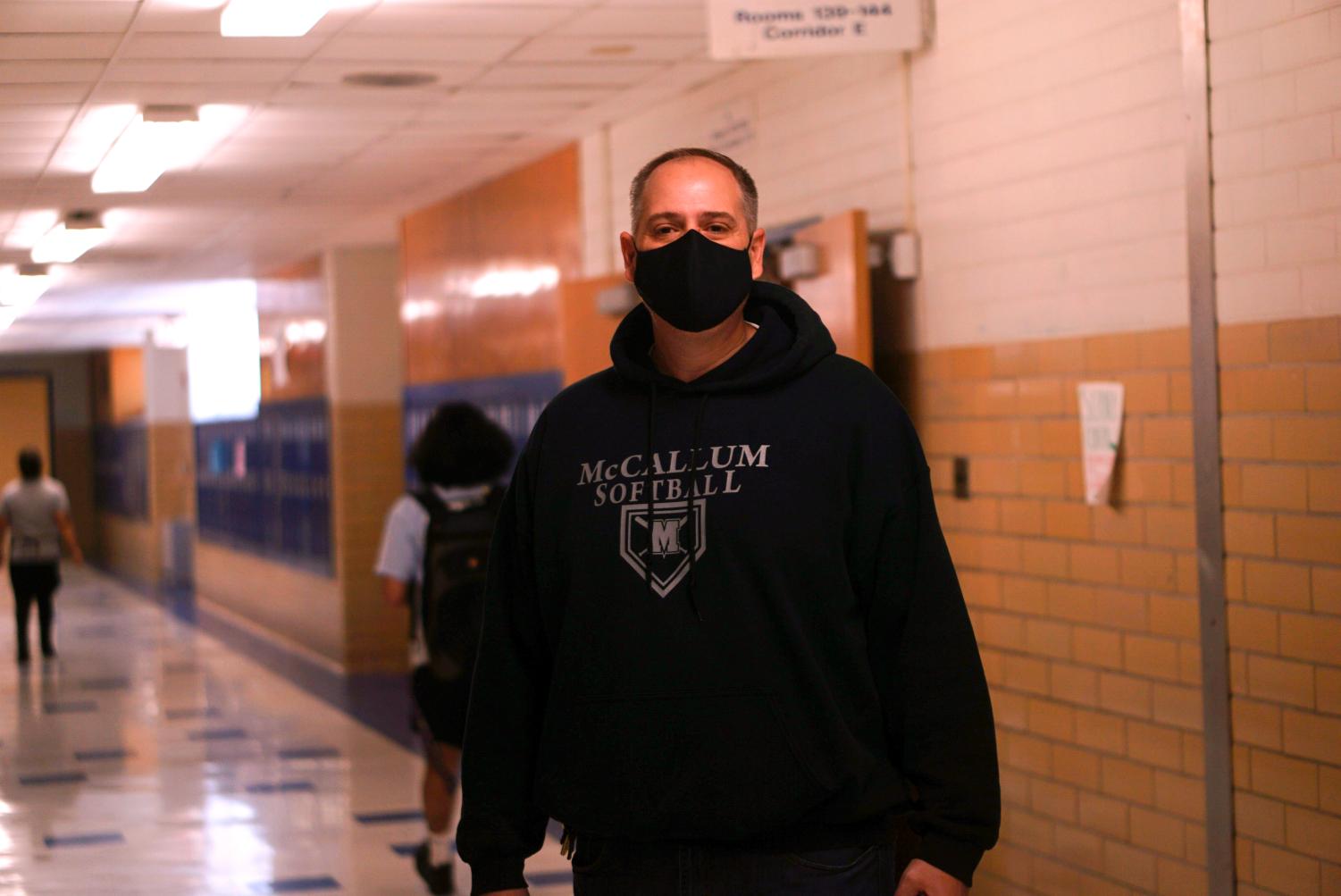

With teachers being expected to teach seven periods next year instead of the six they currently teach, assistant principal Andy Baxa explains that the school will need to employ fewer teachers to cover classes. By employing fewer teachers, the district will save money.

English teacher Diana Adamson, however, believes that before the district can lay off teachers, many of them may decide to leave the profession voluntarily. She worries that many of the teachers who will leave will be seasoned, which may result in a less-experienced staff.

“What I don’t know is how many teachers would have to leave before we have to get rid of teachers,” Adamson said. “The district is saying they don’t think we’ll have to get rid of them because there will be enough that leave.”

Elizalde acknowledge in the Dec. 13 email that the district is “overstaffed” and is currently “spending more on payroll than is funded by our current enrollment.” While that might be true across the district, social studies teacher Kristen Wachsmann claims it isn’t at McCallum, with students regularly being sent to the cafeteria when neither teachers nor substitutes can be found to teach a given class.

“If one doesn’t know what’s happening at each individual campus, you see this macro-picture the superintendent has painted that we’re overstaffed,” Wachsmann said. “Perhaps that’s true when you’re looking at all the numbers together, but we know, looking at a micro-level at McCallum, that’s not true. Sometimes we don’t have enough TA’s, sometimes we don’t have enough custodians, sometimes we don’t have enough teachers.”

As far as what’s driving the sudden scramble for funds, Baxa explains that AISD’s current budget problems are heightened by the fact that AISD’s bond ratings would drop if the district continues tapping into their reserve funds and running a budget deficit.

“There was a deficit for this school year, and they’ve made up the funds through a surplus fund that we could tap into,” Baxa said, “but the reserve has been depleted now to the point where, if you’ve listened to the last couple board of meetings, they’re concerned that if that fund continues to be depleted, it will start affecting their bond rating and their ability to generate capital for physical improvements down the road.”

In Elizalde’s Dec. 13 email, she also announced pay raises for classified staff, such as custodians and food service workers, and teachers. It is Baxa’s understanding that the money for these potential raises will come from budget cuts at the central office and will likely not affect McCallum’s 2022-2023 budget.

Teach more, plan less

“Teachers are definitely concerned,” Baxa said. “In their minds, effectively, they’re being asked to teach 30 more people with an hour and a half less every other day to plan for it. I can understand the concern in that situation.”

Baxa explains that the school is doing what it can to help ease the transition for teachers.

“We’re trying to be as proactive as we can to try and collaborate together to develop plans and systems together that can make it easier for teachers. Looking at things like peer grading and peer reviews to take some of the heavy lifting of grading off teachers and maybe have the students do a little bit more of the evaluation to help with critiquing.”

Senior Marina Garfield, however, is concerned that this increase in peer grading may decrease the quality of education that students are receiving.

“Peer grading is helpful on occasion, but at the end of the day, the peer was not the one who went to school and studied in the areas taught,” Garfield said. “And so even though you can gain very valuable insights from peer grading, at the end of the day, it’s so important to have an actual teacher or certified teacher teaching you and not peers, because that’s not what school is.”

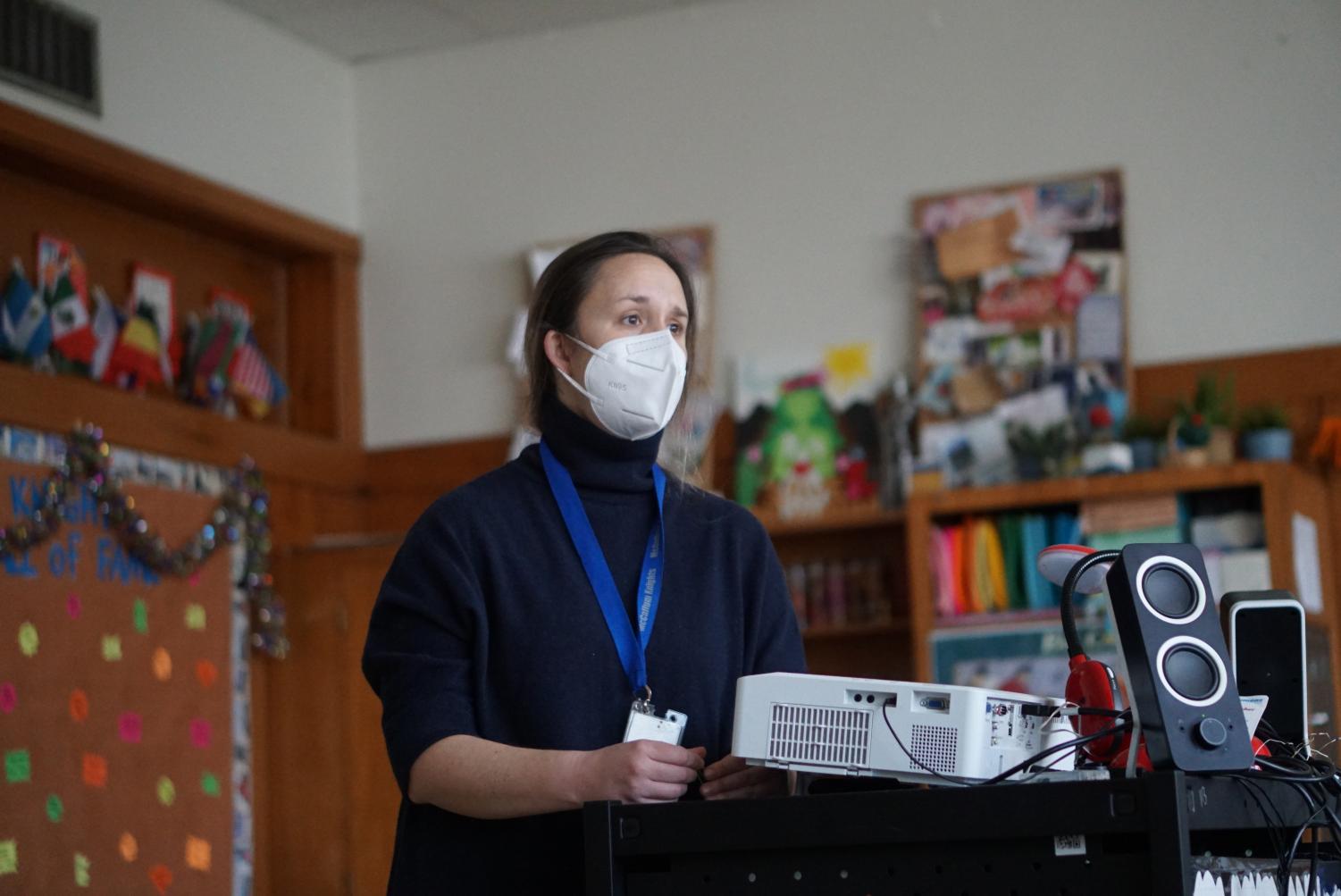

Social studies teacher Kristen Wachsmann doubts that the school’s efforts, while well-intended, will yield productive results. She explains that after the schedule shift was announced at the staff meeting, the administration extended an invitation to staff members to join a committee discussing productivity strategies.

“I can’t speak for all teachers, but to some degree, I found that insulting,” Wachsmann said. “I’m an incredibly efficient, productive person, and I maximize all of my class time and all of my free time. I think any student who’s been in my class would say the same, and any teacher who’s been in my teaching-learning committee would say the same. Any improvement is at the margin.”

While Wachsmann feels the change in approach will produce only a nominal improvement, the impact of having another class to teach will cause a drastic change as teachers will have to teach four periods (the whole day) twice a week.

“Let’s pretend I could become more productive,” Wachsmann said. “We still have the issue of a teacher, every other day, having no break besides lunch and potentially interacting with 140 students in a nine-hour block. And that is not sustainable. That’s too much for one person to handle.”

Besides the increased pressure of teaching more class periods, Adamson believes that switching to this new schedule will only exacerbate pre-existing teaching inequities.

“No matter how we slice it, there’s going to be inequities,” Adamson said. “There’s going to be inequities from teacher to teacher, inequities within the classroom and school itself. The very students who need us the most are going to be harder to reach because it will be harder to make those connections with those kids.”

Garfield agrees that the increase in teaching periods will deepen inequities, explaining that teachers may feel pressured to prioritize certain classes over others.

“If a teacher is teaching a regs class and an AP class, I feel like they’re going to put more emphasis on the AP class, even though the regs kids do deserve that time and constructive feedback,” Garfield said. “Some kids are going to feel prioritized.”

Senior Bobby Currie, who’s previously worked with the Student Equity Council to identify equity issues in schools, believes that such a dramatic shift will only bring deep-rooted inequities to the surface.

“We already have a lot of equity issues embedded in our district that have remained underlying and below the surface,” Currie said. “With a big, dramatic shift like this, I think it will bring everything up. It’ll be chaotic.”

Adamson also worries that the new schedule will take time away from teachers updating and expanding their curriculums.

“We’re all working hard to create a more equitable, diverse curriculum that brings in new ideas,” Adamson said. “And the more we have to do, the harder it is to plan, the less of that we can do. What that means is that we’ll revert back to what’s easy and what we know because making new curricula is hard.”

With the teachers having less time to create their curricula, Adamson believes that the district will push forward its own curricula more and more.

“I think that’s their answer,” Adamson said. “Like, ‘y’all don’t need to plan your curriculum because we’re going to be giving it to you.’ I don’t want their curriculum.”

Despite the new challenges the schedule poses, Baxa maintains that he believes McCallum teachers will persevere.

“I believe in our teachers,” Baxa said. “I believe our teachers will still deliver the same high-quality instruction. I know it will be stressful for them though. … We’re doing everything we can to support them, and we’ll continue to think of new and creative ideas.”

While Wachsmann acknowledges that the school is trying to be supportive in this shift, she doesn’t believe the school has the proper resources to relieve the teachers’ burden.

“I think they’re doing the best with the resources they have, and they don’t have many resources,” Wachsmann said. “I also don’t know if they’re doing so great themselves. So can they give me what I need? No. But it may not be available for them to give.”

Moving forward or staying behind?

Currie believes that the district’s new expectations for teachers demonstrate the administration’s lack of care they have for individual teacher well-being.

“I feel like instead of viewing everyone as a team, they’re very like ‘I’m the king and I’m the queen and everyone else is a pawn,’” Currie said. “And they’re not realizing that every good statistic from Texas is based on these teachers that are here every single day and interacting with these students on a much more personal level than the people making these decisions.”

Like Currie, Wachsmann feels like the district too often brushes teachers’ concerns aside because teachers are not the district’s constituents.

“I’m not interested in talking to the district because I haven’t felt heard by them,” Wachsmann said. “Who I want to say something to is the families, because that’s who they’ll listen to. A lot of times, families, especially if they don’t know someone in education, don’t understand the impact. And I’m telling you, I’m screaming it: This will have a negative impact on education. This will have a negative impact on your student. So say something, do something about it before the change is permanent.”

English teacher Nikki Northcutt believes the district’s treatment of teachers represents more than just their indifference, but active malicious intent.

“I think that everyone knows that teachers are overworked, but I don’t think that the people in power really care. And worse, I think that the people in power at the state level are actively trying to make our jobs more difficult because they have contempt for public education.”

According to Wachsmann, many teachers have been discussing leaving next year, both publicly and privately. Though Adamson has considered retiring next year, as of now, she plans to return next year.

“I think that if at some point we don’t start saying no, it’s not going to get any better,” Adamson said. “And yet, it’s hard. … I don’t know when to start saying no because I feel such a strong sense of loyalty to that McCallum brand, to my students, to my principal, to my English department. I don’t know how to say no, but I think we need to.”

Northcutt, however, has decided that she will be leaving for the 2022-2023 school year.

“I love this job and I love McCallum High School,” Northcutt said. “I feel like I am in the best school in the district. I love my colleagues and my students. But I refuse to burn myself out. I am already working all weekend. I cannot give any more than I am already giving.”

Wachsmann, who recently gave birth to her first child, believes that the district is taking away her ability to properly care for herself and her new family.

“If I suffer, can I take care of my own child?” Wachsmann said. “And then it feels personal. Like, ‘Ms. Wachsmann, please take care of these 180 students’ at the cost of being a parent and love my own child in the way that I want to. And that feels wildly unfair.”

Ultimately, however, she explains that the district’s decision has called into question whether she can sustainably continue her career in education.

“The decision, at its core, makes me not feel appreciated,” Wachsmann said. “Part of my fulfillment is being taken away there. And now, to do this job, I’m being asked to sacrifice myself. And while I’m happy to be a public servant, I’m not going to be a martyr.”

—with reporting by Morgan Eye and Grace Vitale

This story was originally published on The Shield Online on February 5, 2022.