Afghanistan To Albemarle

Adapting To Life 6924 Miles Away

Eavan Driscoll

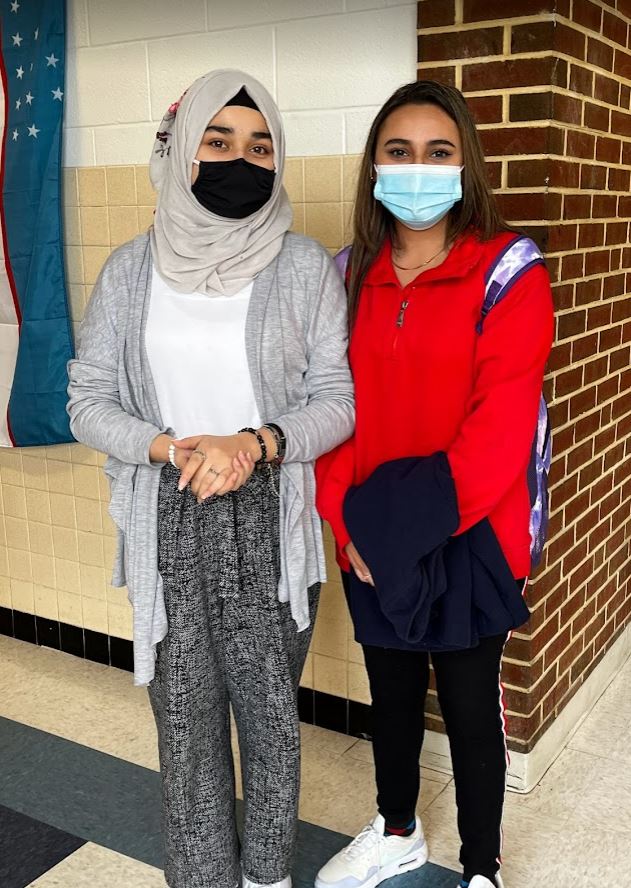

Freshman Sadaf Ashrat and Junior Jazil Choudhry together in the upstairs hallway after Winter Break.

February 9, 2022

Since opening in Charlottesville in 1998, the local International Rescue Committee (IRC) office has resettled 1,444 people from Afghanistan. However, over the past 23 years, the Charlottesville IRC has never had overflow like now.

Between Oct. 1 and the beginning of December, the IRC has brought 210 Afghan refugees– including 75 families– to live in the Charlottesville/Albemarle area.

Turmoil in Afghanistan and advances of the Taliban as well as complications with the Isis terrorist group have forced more than 600,000 people to flee since January 2021.

The United States enacted an evacuation by air before retreating from the country on Aug. 30, ending the 20-year war with Afghanistan. 123,000 civilians were saved by plane, while many more fled the country by foot to neighboring countries Iran and Pakistan.

“It was so, so scary but we were just happy to make it out of Kabul alive,” freshman Sara Frotan said. She was one of the lucky ones who made it on a US plane, before the Abbey gates of the Kabul International Airport closed for good.

Compared to other countries, the United States is housing a small portion of the Afghan refugees; however, director of the IRC’s Charlottesville office Harriet Kuhr expressed the struggle the IRC is having trying to manage all the families.

“Resettling families is easier said than done,” Khur said in her interview with NBC 29 on Nov. 19.

As of Oct. 14, more than 7,000 evacuated Afghans were still living in hotels around the United States. The majority of refugees in Charlottesville remain in temporary housing today, living in hotels or staying with previously-settled family members.

Freshman Sadaf Ashrat arrived at school Nov. 22 after escaping Kabul with her family. Ashrat’s plane went from Kabul to Qatar to Germany and finally to the United States where she and her family of seven were housed in two hotel rooms for three weeks.

“The hardest thing about coming to Charlottesville has been trying to learn English and communicating with people,” Ashrat said through Urdu translator junior Jazil Choudhry.

During her flight, Ashrat had very conflicting emotions because she was “sad to leave her friends and family behind, but happy and excited to come here and start a new life.”

Ashrat had family already settled in America. They, with help from the local IRC, helped her father to find the apartment that they live in now.

In addition to housing, IRC members have been aiding families with benefits applications and enrolling in school.

AHS has been working closely with the IRC to communicate about new arrivals and prepare teachers for more students. ESOL department chair Erin England is the first line of support for English learners coming into school.

Our goal is to “help them [any new student] feel comfortable and safe in this new environment,” England said.

Since school began, two Afghan students have joined the school in addition to students registered at the beginning of the year. As of Dec. 16, there are 5-7 new students registered and expected to join before the second semester. That number will only rise as more families move out of hotels and can register their children for school.

“There is no magic number of how many kids to expect, all we know is to be prepared for more,” principal Darrah Bonham said. “We have always been a hub for people from other countries.”

More refugee families tend to settle in the AHS feeder pattern because there are greater affordable housing opportunities, England explained.

Without a home address, kids cannot be enrolled in public school. This has enhanced the urgency of finding permanent housing for refugee families in the Charlottesville community.

Now that she is living in an apartment, Sadaf and her siblings have been able to receive an education in the United States. “School is different here. In Afghanistan there were separate schools for boys and girls,” Ashrat said. “There were also uniforms that included hijabs in the school building.”

Ashrat’s favorite class at Albemarle has been algebra, but she has generally had a difficult time understanding what any teacher is saying.

While she speaks Pashto, Dari, Farsi, Persian, and Urdu, Ashrat is only beginning to learn English.

Ashrat’s translator, Choudhry, said that “sometimes students new to the school feel really, really lonely, especially when they don’t speak the language of everyone else. I used to feel lonely too, coming to America is a huge culture shock.”

Ashrat is Muslim and performs Salat (prayers) in school around noon and during fourth block. She is used to school stopping for prayer in Afghanistan, so it is a bit different to leave class to pray. “It is not hard to pray in school,” Ashrat said, “We just go to the counselor’s office when we need.”

This is Choudhry’s first year at AHS too. She moved from Pakistan in 2019 and has lived in Maryland, Danville and now Charlottesville.

Choudhry speaks Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, and English, reads Arabic and is also learning Spanish. She has been a big help to new students coming into the building from India or Afghanistan. “I have led students through the building, and my friends and I try and help them to feel welcome.”

“Sometimes I am tired and mix all my words up from different languages, but I am glad that I can talk to so many different people,” Choudhry said.

Currently, there are no Dari, Pashto, or Farsi speakers among the ESOL teachers, which makes direct communication with Afghan students difficult. To help bridge this gap, a member of the local IRC joins new students on their first day of school and remains in contact with them and their families throughout the year.

“Imagine if your family suddenly moved to a country where you don’t know the language,” England said, “empathy and awareness are crucial.”

When there is no IRC member to help interpret, ESOL teachers use an app called “Interpret Talk” to communicate, or sometimes other students who speak the same language, such as Choudhry, to help translate.

Frotan is another student who has been helping other Farsi speakers to adapt to the school. “I love to help other people,” Frotan said.

Frotan translates for her family and other families as well. She has helped with everything from paperwork completion, grocery shopping, and even medical emergencies.

Other than a language barrier, economic challenges can build up on refugee families.

“They [refugees] come to the country without a car, house, shelter, or job, “Frotan said. “Just try to be kind to them, you don’t know their home life.”

It is important to “open ourselves up to understand others,” Bonham said.

Despite missing life in Kabul, Ashrat has adapted to her new life in America. “Everything has been alright at school. Students and teachers have been helpful,” she said.

Ashrat enjoys her studies and said that she has goals of becoming a doctor or businesswoman. England has been helping her to get closer to those goals, aiding with homework and translating assignments in class.

“School in America is a blessing,” Frotan said. She said that teachers here have been kind and understanding with her.

“People in America would watch a scary movie and think that was scary, but these students’ lives were horror movies,” Frotan said.

Frotan just wants our school to be “As helpful as possible to these new students and give them a safe place to learn.”

“Even though they don’t speak in your language, you should try talking to them and be friendly so they can feel comfortable here.

You should always try to put yourself in their shoes,” Choudhry said.

As the school year reachers the second semester, the IRC has been trying to get as many families out of hotels as possible.

This story was originally published on The Revolution on February 1, 2022.