Fentanyl in St. Louis

Recent overdoses have exposed a worrying new trend in the St. Louis region.

March 10, 2022

Kenjo Bell decided she did not want to die anymore. “I realized I had no one to blame. Everything I had been through was a reflection of my decision-making. I knew I longer wanted to be who I was but instead the person others had once told me I could be.” Bell’s experience is hardly unique: tens of thousands of Missourians struggle with fentanyl use. The CDC notes that from 2013 to 2019, the rate of synthetic opioid deaths has increased thirteenfold.

Fentanyl is often called the third wave of the opioid crisis. The first wave began when pharmaceutical companies such as Purdue Pharma launched aggressive campaigns to get doctors to prescribe drugs like OxyContin. These campaigns got doctors to prescribe OxyContin for a wide range of maladies beyond treatment for late-stage cancer patients. Soon, millions became hooked, and when prescriptions began to run dry in 2010, the second wave of the epidemic began: heroin.

Heroin is made from morphine, a natural product of the opium poppy. Heroin has very similar effects to prescription opioid painkillers like OxyContin. The similarity between the two types of drugs ultimately drove many former users of prescription opioids to heroin, as it became easier to obtain. According to a government study, 80 percent of heroin users stated that OxyContin was their gateway drug.

Soon, a worrying new trend would emerge: The rise of synthetic opiates also called opioids.

Opioids are created in labs and are significantly more potent than the natural variety. Ben Westhoff, the author of Fentanyl, Inc.: How Rogue Chemists Are Creating the Deadliest Wave of the Opioid Epidemic, explained how fentanyl and other synthetic opioids enter the US market. “Illicit fentanyl is almost all made in China. And until recently, types of fentanyl were legal in China. Now, often fentanyl and its analogs are banned in China. But China still makes the precursor chemicals which are like the raw ingredients, which is legal. So what happens most often is they sell to Mexican cartels, and the Mexican cartels make the finished fentanyl and send it to the border into the US.” The cartels then sell the finished product either as pure fentanyl or mix it into other drugs.

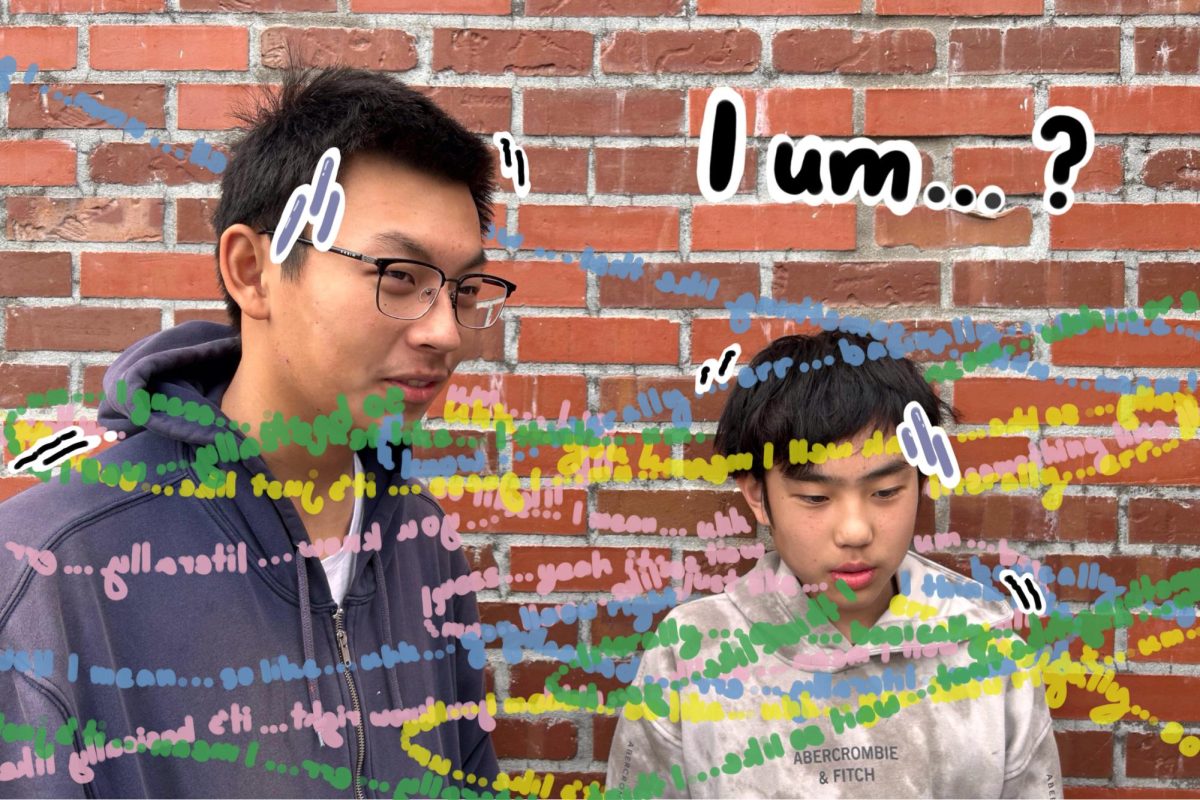

One of the most common ways for fentanyl to be purchased and distributed is through the dark web and social media. DEA public information officer Andree Swanson pointed out how social media is used by dealers to distribute fentanyl. “Between the smartphones and social media, it has put the drug dealer in your home. If you have access to a smartphone and you have Snapchat or Instagram or any of those kinds of social media apps, you can find the drug dealer on it, and they can sell you drugs.”

Social media and the dark web have changed the game in drug use. Now illegal and dangerous drugs like fentanyl can be purchased with ease. Social media has hooked a new generation of younger people to opioids.

Fentanyl has seen a meteoric rise in recent years due in part to its potency. To help understand how dangerous fentanyl truly is Swanson recommends picturing a standard sugar packet. “Take a packet of sugar [2 grams] and pour it in your hand. If this were fentanyl, it could kill 1000 people.”

From 2015 to 2017, synthetic opioid deaths increased from 4 deaths per 100,000 to 8 per 100,000. In the twelve months between April 2020 and April 2021, more than 100,000 people died of drug overdoses. In St. Louis, overdose deaths increased 20 percent each year since …according to the CDC. This meteoric rise is credited to fentanyl and other analogs, with estimates that approximately two-thirds of all drug deaths can be attributed to synthetic opioids. On February 5th in St. Louis, an overdose killed seven people. Brown was not surprised when she heard the news of this most recent overdose.

“Overdose deaths have become so common, and the numbers continue to rise. There just is not enough funding, resources, or treatment facilities for those to receive the help they need and even want. The other part that saddens me is that many are unaware they are even putting fentanyl in their bodies as so many other illicit drugs are cut with fentanyl,” said Brown.”

Swanson shared that “the individual who was arrested is accused of distributing cocaine that was with fentanyl.”

One of the things that have made it difficult to tackle fentanyl is that other drugs are laced with fentanyl. Fentanyl is cheap to produce through intricate modern supply chains and, as such, has become an attractive tool for the cartels. They figured out that it was much cheaper to dilute drugs and then add back in fentanyl than keep the drugs pure. The issue with that is there is little margin for error. Just two milligrams of fentanyl can be lethal.

According to DEA data, two-fifths of counterfeit pills contain a lethal dose of fentanyl.

There is a way to combat the rising fentanyl deaths: fentanyl test strips.

On Jan. 9, 2022, Representative Trish Gunby of Missouri’s 99th congressional district introduced House Bill 2570. HB 2570 would create a new Missouri pilot program to distribute test strips free of charge. Gunby introduced this bill after seeing a need. “Everybody in the legislature says that we’re at a crisis when it comes to opioid deaths. It’s an urban issue. It’s a rural issue: and we have a chance to save lives.”

This program would provide funding to the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services to begin the process of distributing test strips. States that have already implemented such programs have seen successes according to studies conducted by Johns Hopkins University and Brown University. Gunby notes that passage of this bill will not be easy.

In response to critics, she said, “They’re addicted. It’s a disease. They’re not trying to die. They just are dying. Because they don’t know what they’re ingesting. So I think that something like this, gives them the wherewithal to say, you know, I just want to, I don’t want to die. I mean, how many times do we hear accidental overdose? People don’t know what they’re ingesting. So this is a way to just prevent that from happening.”

Nichole Dawsey of PreventEd appreciates programs like Gunby’s. “We promote fentanyl test strips and distribute them at PreventEd,” Dawsey said. “While we certainly don’t encourage drug use, we also recognize that fentanyl test strips keep people alive. They are one strategy, but certainly not the only strategy. Education helps prevent use in the first place, and medication-assisted treatment has proven very successful.”

Nurse Lisa McDade at Clayton High School supports a test strip program, saying, “It’s not going to encourage people to do drugs more. I don’t necessarily think they want to be like users in the way that they are, it is just the addiction to it and it’s horrible.”

Kim Sherony of the All in Coalition also supports a test strip program: “Fentanyl test strips are an effective way for people, typically those who are chronic substance users, to be able to detect if fentanyl is in a drug that they intend to use. This in conjunction with Naloxone, which is the opioid overdose reversal drug, are life-saving strategies. The ultimate goal with these harm reduction strategies is not necessarily to enable continued fentanyl use but rather to keep the person who is using alive so that they will eventually get the medical treatment they need.”

This leads to perhaps the most famous tool in fighting the epidemic, Naloxone.

Narcan, or its generic name Naloxone, is a drug used to treat opioid overdoses. It was first patented by Daiichi Sankyo in 1961 and approved in 1971. Since then, it has saved countless lives from almost certain death. In response to this epidemic, all Clayton nurses and school resource officers carry and are trained to use Naloxone. The drugs came initially from a relationship with a local pharmacist who used to supply facility flu shots.

While McDade says she has never had to use Naloxone, she is still vigilant.

“We’re ready for any emergency that comes our way. If I were to see somebody it’s like, my brain will always go to like, why are they unconscious? It would be one of the differential diagnoses I have in my head like, is it a diabetic emergency, or are they having cardiac arrest or even a drug overdose?” said McDade.

Another program that can be used to treat this epidemic is Naltrexone or Vivitrol. Naltrexone is a drug that’s used to treat recovering opioid addicts. It is delivered intramuscularly and is very effective in keeping former addicts clean. The drug works by blocking the effect of opioid receptors and decreasing cravings to use opioids. This drug has become a favorite of paramedics across the US, including in Clayton. There is now a push in Missouri to make this drug more readily available. Senate Bill 1037 introduced by Senator Holly Thompson Rehder would, if passed, allow for pharmacies to sell the drug directly rather than keep the drug behind the counter. This could potentially be a game-changer as it could increase the availability of treatment to addicted individuals. The future of SB 1037 is still very much in jeopardy as it is still early on in its life and many months from passage.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, education is a tool that can be used to treat this epidemic. Dawsey believes that education is critical in fighting this epidemic, especially in schools.

“Schools need comprehensive, prevention education beginning in kindergarten. Clayton has this; many districts do not. This, coupled with adequate counselors, social workers, and nurses makes a huge difference,” said Dawsey.

Shelby agrees, “The education that students receive in health classes, conversations with their parents around substances and being involved in activities that support their mental wellness are all examples of effective ways to prevent substance use problems in youth. Prevention messaging in schools needs to not only focus on the known adverse effects of using substances, but also the unintended effects, like the possibility that a drug could be laced with something else, such as fentanyl.”

Today, Bell works as a peer support specialist and a substance abuse counselor where she helps others like her former self recover from addiction. Her role entails leading group and private sessions and sharing her story. She credits in part her recovery to her current work.

“Recovery starts out mostly as something we do and gradually grows into something you feel and live,” said Bell. “Stories of others help to inspire me, enhance my hope, stay human and humble. Most importantly for me though they help keep me grounded in remembering where I came from, how hard I worked, and what I desperately never want to find my way back to again.”

This story was originally published on The Globe on March 6, 2022.

![Delicately placing the string to form the shape of a cornucopia, seniors Haley Burton and Avery Nelson create the November arrangement for the Flower of the Month Club. This club is led by Advanced Floral Design Students and provides a monthly arrangement to community members who subscribe to receive them. “I think flower of the month club is a really impactful way to show your loved ones ‘hey I really care about you,’ or even if they’re just for yourself, they’re a little pick-me-up throughout the month that [say] ‘I’m doing ok, and these flowers make my day a little bit brighter,” Nelson said. “I like giving people flowers because people value the flowers more and they value themselves more.”](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Ava-Holmes-3-edit.jpg)

![Within the U.S., the busiest shopping period of the year is Cyber Week, the time from Thanksgiving through Black Friday and Cyber Monday. This year, shoppers spent 3.3 billion on Cyber Monday, which is a 7.3% year-over-year increase from 2023. “When I was younger, I would always be out with my mom getting Christmas gifts or just shopping in general. Now, as she has gotten older, I've noticed [that almost] every day, I'll open the front door and there's three packages that my mom has ordered. Part of that is she just doesn't always have the time to go to a store for 30 minutes to an hour, but the other part is when she gets bored, she has easy access to [shopping],” junior Grace Garetson said.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/DSC_0249.JPG-1200x801.jpg)

![French teacher Marieme Toure serves a plate of the Senegalese food she prepared for her AP French Language and Culture class, to senior Faiza Syed. “I never had Senegalese food before,” Syed said. “I thought it was so cool that she was able to bring a part of her culture [and] background to us.”](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/IMG_0798-1200x906.jpeg)

![NEW CHALLENGE, NEW TEAM MEMBERS: Every season, VEX creates a new game that robotics team members are faced with and have to build a robot to compete in. This year’s game forces students to create a robot that is able to stack rings onto mobile goals in order to score points. The change in games each season is something that robotics teacher Audrea Moyers appreciates.

“One of the things that I like about VEX is that they have a new problem to solve every year,” she said. ¨Even though the equipment’s the same, they have to analyze the game, and they have to come up with solutions that are unique that year. They are using their knowledge from prior years, but they have to kind of redesign a problem.”

As returning teams were faced a new game, some new teams and members had to adapt to a uncommon playing field and game.

“Three of our four teams were competing for the first time this year, and they had very different experiences match to match, so I think they learned a lot,¨ she said. ¨It’s hard just watching a video online to know how it’s actually going to be in person, so they all learned a lot about what gameplay is like, how to work with an alliance partner [and] how to adapt during the day to changes.”](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_9283-1-1200x800.jpg)