“We are going back to our country.”

Joyce Lee was in kindergarten when her mom broke this news to her on what was supposed to be a mundane day in Davis, California.

Soon, the Lee family would be packing their many years of life in America into boxes to be shipped to South Korea — Lee’s parents’ country.

For Lee, born in America, the move meant many things. First and foremost, it meant no more plum picking with her dad from their backyard tree. No more raiding the den of the brown and white pet rabbit Alice. No more collecting rolly pollies and spiders into emptied kimchi jars to be proudly displayed on the stand right next to the 50-inch Black Sony. Most importantly, in Lee’s mind, it meant she now had to be Korean, not American.

“I almost needed to completely do a 180 and pretend that I was born in Korea, even though I was completely American,” she said.

The day after the news broke, 6-year old Lee vowed to stop speaking English.

“I’m now Korean,” Lee declared to her mom. “Speak Korean to me.”

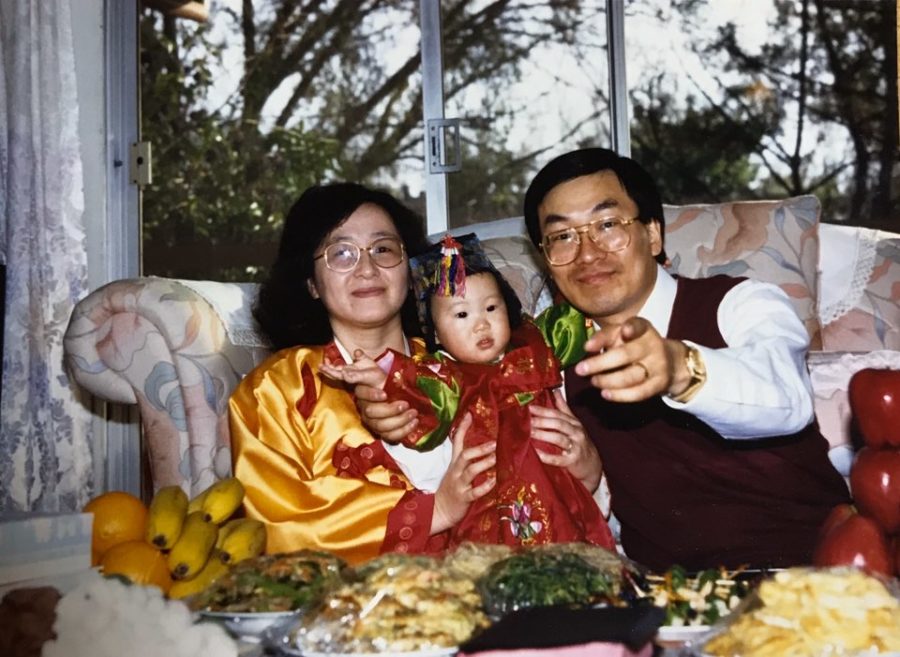

For Lee’s parents, who had immigrated to the U.S. as international students from South Korea in the early 1980s, the move back to their home country meant a new start where they would actually be able to reach their potentials in their careers.

“My parents struggled a lot in their workplaces,” Lee said. “There was a lot of competition in America. There was a lot of xenophobia and microaggressions — basically racism — which made it really difficult for my parents to do what they wanted.”

Despite having a PhD in mechanical engineering, Lee’s dad was stuck at an unfulfilling teaching job, while Lee’s mom was stagnating in the post doc cycle and unable to secure a more permanent faculty position.

“I think my mom internalized the message that she was forever a foreigner and an international student,” Lee said, “and I think that really took a toll on her mental health.”

Lee’s mom decided she would no longer look for a university position in the U.S., and concurrently, her dad began searching for opportunities back home in South Korea, eventually landing a job at Inje University, a private research-intensive university. As Lee understood it at the time, her father securing this post was the reason why she had to leave Davis, California, why she had to leave her rolly pollies and Alice.

Nabi the cat. A calico kitten. Lee’s only friend in the kindergarten in which she was enrolled after the move to South Korea. Nabi, which means butterfly in Korean, is a common name given to street cats, who wander and find friends and sustenance where they can.

During recess, nobody wanted to interact with Lee. She was American. She couldn’t speak Korean. She was an outsider.

“I couldn’t read the language, I couldn’t write it,” Lee said. “And if you spoke English in Korea, you felt stigmatized because you wouldn’t blend into Korean culture. I was pretty much shunned. Nobody wanted to play with me.”

So she befriended Nabi.

It wasn’t only her classmates who found her problematic, however. Teachers were befuddled too. In the U.S., she had been raised to share her opinions and be assertive, but in Korea, this way of expression drew only rebukes.

“When I spoke my mind, they thought that I was disrespectful,” Lee said. “When I even just made eye contact, they thought that that was absolutely out of order.”

At the time, in Korea, corporal punishment, such as paddling, was still legal in schools.

“Teachers could basically hit you without justification,” she said. “If you talked, spoke up, or even looked at your teacher a certain way, you would be paddled. I was subjected to that many times, sadly.”

Lee endured these challenges for five years, until at 11, she felt she had had enough. At that point, Lee started to truly feel like she didn’t belong in South Korea.

“I’m American,” she thought to herself. “What the heck am I doing here, trying to be someone I’m not?”

For three more years, Lee begged and pleaded to return back to the States, an entreaty to which her parents were hesitant to agree to since Lee was still young in their minds, and they were now flourishing in their professional lives.

“I need to go back,” Lee urged them repeatedly. “This just does not feel like home.”

When she was 14, her parents finally acquiesced, allowing her to return back to the States. Only they would not go with her. She would make her new home with family friends back in Davis. Her parents would remain in South Korea.

The time Lee stayed in Davis apart from her family was “tremendously difficult.”

“I cried almost every night,” Lee said. “I was having a hard time not only adjusting back to the culture and language again, but I was just feeling really isolated from not being with my family.”

Six months later, she called her parents, telling them, “I don’t think I can do this any longer. I need family.”

On the surface, the agreed-upon solution seemed beautiful. Lee’s paternal grandparents, who had retired, were willing to uproot, make the trip, and move into an apartment for three. The only problem was they didn’t speak “a lick of English.” Still a middle schooler, Lee was thus pushed into the position of constant language brokering. She paid the bills, went to the grocery, and did “a lot of translation.”

“At that point, my main mission became helping my grandparents survive in America,” Lee said, “and it just got really difficult.”

Another six months later, she called her parents, telling them, “I don’t think I can do this any longer. I can’t take care of grandma and grandpa. I need one of you to be with me.”

So Lee’s grandparents returned to South Korea and her dad came to the States for a year as a visiting professor at UC Davis. Until she graduated from high school, Lee’s parents alternated yearly status with her in Davis.

Regardless of this challenging childhood, Lee never gave staying in the U.S. a second thought.

“It didn’t even cross my mind that I would go back because I knew what life in Korea would look like, and I really, really didn’t want that,” she said. “I was quite lonely there, especially in the early years, and I just felt like I wasn’t truly who I was meant to be.”

Holmes Junior High. Food and Nutrition class. Davis, California. Lee was wearing a pink polo and a pleated skirt. The teacher asked a question, and Lee assertively raised her hand to respond.

“I just remember the feeling of ‘Wow, this feels really empowering,’” she said. “I felt so liberated to be able to just speak. It didn’t matter if my answer was right or wrong. I felt like my opinions were unique, and it meant something to me to be able to express them without censure.”

When the teacher called on her, and she said what was on her mind in response to that question, Lee thought to herself, “This is why I’m here.”

Having had such a complex journey, to Lee, demeaning phrases that are sadly, sometimes uttered so flippantly by some, like “You don’t belong here,” invalidate all of these past hardships.

“It’s hurtful. It’s painful,” she said. “I am just as American as any other citizen in this country. I have access to the same rights the Constitution of the U.S. gives to all citizens. I consider this my home. I belong here. I belong with my rolly pollies and Alice. This is my land. This is where I stake my claim.”

This story was originally published on The Emery on January 20, 2022.