If you’ve been on social media this winter, you’ve probably come across the rising fashion trend of wearing “balaclavas,” a cloth garment worn around the face that covers most of the wearer’s hair and neck. Historically, balaclavas were worn as ski masks, used to prevent frostbite in extreme conditions. Originally conceptualized in 1854, the garment finds its historical roots during the Crimean War. In fact, it was named after a small town in Crimea where British troops were stationed. Due to the freezing temperatures and lack of proper winter attire, British families sent their troops knitted wool “balaclavas.”

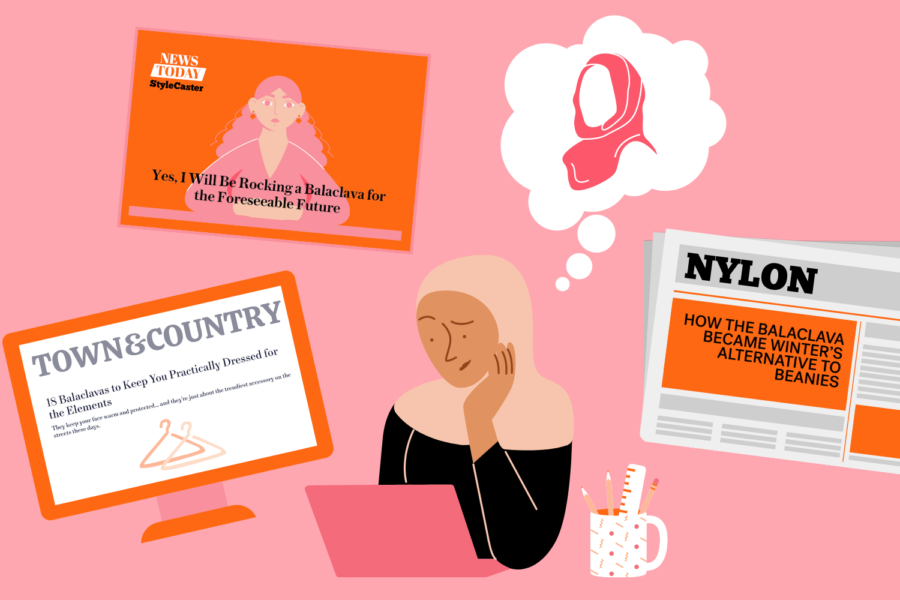

Recently, balaclavas have gone from ski masks to “trendy winter accessories.” My timeline is flooded with tutorials on how to crochet your own trendy balaclava, photos of models wearing designer balaclavas at Paris Fashion week, and Instagram influencers coming up with ways to style their new colorful accessories.

Here I am, a proud hijab-wearing Muslim woman, scrolling through my phone and seeing all these pictures of people covering their hair and necks and coining it a new fashion trend, thinking, “Hmm… This looks a lot like what I’m wearing…”

While my immediate reaction was one of curiosity, once I realized the magnitude of this “trend,” I started to feel frustrated. Women wearing balaclavas are being praised and imitated for their sense of style, while I go out into the street every day fearing that an almost exact replica of this garment sitting on my own head will subject me to physical or verbal harm.

Now, you might be wondering why I am criticizing people for wearing this piece of fabric. Can’t people just wear what they want? Believe me, that is the same question I pose to myself whenever I see a headline announcing another hijab ban, a high-schooler who had her hijab ripped off at school, or even when I myself experience Islamophobia in Nashville.

Of course, people should be able to wear what they want, and no one should be able to dictate that or shame others for the way they choose to present themselves. Unfortunately, Muslim women who choose to dress modestly and wear the hijab are rarely awarded that privilege.

On Jan. 13, the New York Times published an article that finally put my thoughts into words. The writer interviewed Sagal Jama, a popular hijabi influencer, who was at first very excited about the notion of head coverings becoming more popular and normalized. However, she later realized the negative implications it holds for Muslim women who deal with discrimination far too often.

“People are able to wear a balaclava and be perceived as trendy or cool, but a hijab can be seen as a symbol of oppression or political,” she said.

As someone who has to think in the morning about wearing a bright pink hijab to look as “non-threatening” as possible instead of a black one that will go better with my outfit, I know that I also hold immense privilege as a white Arab Muslim woman. While Muslim women are often a target of hate and animosity, Black Muslim women are even more so. In the recent rise of hate crimes against Muslim women in Alberta, Canada, ten out of the fourteen attacks have been against Black Muslim women.

“In the context of the balaclava fad,” said Anna Peila, author and visiting scholar at Northwestern University who specializes in topics of feminism in Islam and Islam in popular culture, “it’s not just whiteness — it’s the white femininity that is read as non-threatening.”

To me, seeing people slipping on a balaclava and gaining thousands of likes on Instagram just feels like a slap in the face. The ease that non-Muslims experience whenever they wish to express themselves through clothing without backlash is something I long to have.

Additionally, balaclavas don’t only pose internal struggles for Muslim women, they also pose physical, overtly real ones.

Singer-songwriter Nemah Hasan, who goes by @nemahsis on TikTok and Instagram shared a video in response to the rise in popularity of balaclavas, sharing an incident that occurred as a result of this “trend.”

“I’ve been wearing hijab for nearly two decades now, and I’ve recently converted to balaclavas, for over a year,” Hasan said, describing the convenience of wearing the warm garment as a hijab for someone who is always traveling for work.

“They always know it’s hijab at the airport…but I guess since balaclavas have become this fashion statement over the last few months, it’s become more normalized to check what’s underneath them.”

Hasan recalls having lost her voice and being asked by an airport security worker to remove her balaclava. Of course, she quickly tries to explain that her balaclava is actually a hijab.

“By the time he was processing what I was saying, this female security guard behind me comes and rips it off like a hood, and I’m sitting bare,” Hasan said.

Having your hijab yanked off, especially in such a public and stressful environment as airport security, is a hijabi’s biggest nightmare. Or, at least, it’s mine.

“Hijabis, stay safe out there,” Hasan said as she ended the video.

Incidents like this are obviously not the fault of balaclava-wearing individuals. However, they are a side effect, and when we live in such an interconnected world, we have to be aware of the consequences that our actions can have on marginalized communities.

As a Vanderbilt community, our goal should be to eliminate hypocrisy and do our best to advocate for Muslim women. Don’t wear head-coverings such as balaclavas unless you are also willing to acknowledge and support your hijabi peers who face discrimination. Take classes such as “Islam in the Modern World” (great class and professor, highly recommend) in order to learn more about Islam and how it has been portrayed through time. Offer to walk with your hijabi friends on or off-campus. Advocate against hijab bans and have discussions with your friends and family about eliminating bias towards Muslims or any other cultural or religious group who may look different from you.

I would love for you to express yourself through fashion, to try new things and new styles, no strings attached. Sadly, it’s not as simple as that when there are women around you who are constantly fighting to do the same thing.

This story was originally published on The Vanderbilt Hustler on January 30, 2022.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)