For the past few years, the social media platform TikTok has proved to be a powerhouse of trends ranging from one-pan feta pasta recipes to coquette fashion aesthetics.

Garnering over 650 million views this past summer, the trend “#cleangirl” has flooded the pages of the app.

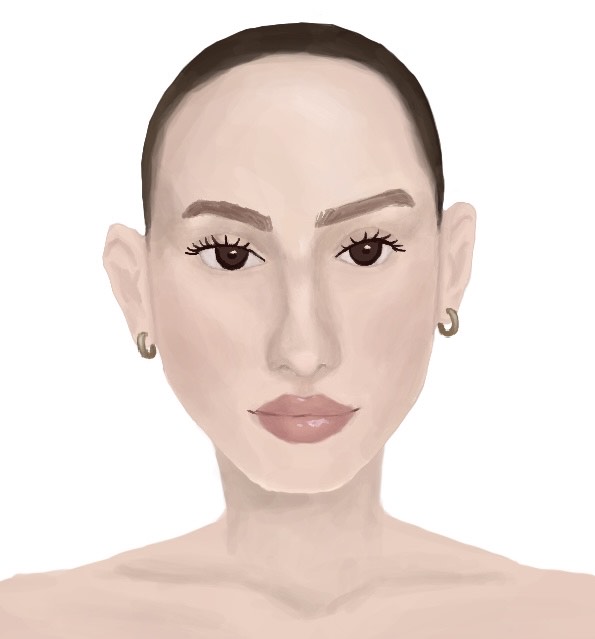

Quote-unquote “inspired” by celebrities such as Hailey Bieber and Bella Hadid, the look is distinctly defined by slicked back hair, gold hoops, glossy lips and the minimalistic “no makeup, makeup look.”

While at surface level, the look appears to be another harmless internet beauty craze, at its core, the “clean girl” aesthetic advocates for harmful social and beauty standards.

Similar, if not identical, beauty aesthetics have existed within Black and Latin communities for decades, yet only resurfaced more recently in its repackaged form — in other words, tailored to be more palatable for the white audience. In the past, women of color [WOC] have been subject to intense ridicule and stereotyping for sporting these same looks and other trademark beauty and fashion features from Black culture including long acrylic nails, protective hairstyles and durags.

Only now that these elements are styled by white influencers does it become more socially acceptable and trendy. In fact, affluent, slim white women have become the face of this trend.

But by doing so, the clean girl aesthetic extracts elements of Black culture for fashion use while promoting Eurocentric beauty standards that entirely deny women of color — the rightful pioneers of these popular movements.

“The clean girl look might suffice for somebody who closer adheres to the beauty standard but if you don’t then you’ll be vilified for not going out of your way to over-perform femininity,” user @its.katouche_ said in one of her TikTok videos.

Like the creator indicated, participants of this trend are expected to fit under strict Western beauty standards, which in itself, is racist.

Likewise, under the hashtags “#cleangirl” and “#cleangirlaesthetic,” the striking lack of diversity is unmistakable. The trend emphasizes fatphobic and classist ideals that view bigger bodies and lower-income communities as undesirable.

Frankly, the term “clean” itself has problematic implications. It suggests that anybody who rests outside of this demographic of rich skinny white women with perfect skin and lives — a.k.a. BIPOC and plus-size individuals with textured skin — then translates to being “dirty.”

The clean girl look is also accompanied by an urban, minimalist lifestyle characterized by 7 a.m. morning routines, beige matching workout sets, high-end beauty products, $8 daily coffee runs and organic green diets. By documenting their unrealistic indulgent lifestyles, content creators further subscribe to this narrative that “cleanliness” can only be achieved with wealth and privilege.

But not only are these influencers endorsing unrealistic lifestyles, they also promote extreme standards that come with mental health consequences, especially for the millions of adolescents that are exposed to this content. These trends and videos give young teenagers an obligation to behave and look the same way as these media figures appear online. In essence, the clean girl movement paves way for lower self-esteem and poor emotional health.

The controversy surrounding this beauty trend also begs the question of whether or not netizens should be allowed to emulate these looks.

Although the “clean girl” trend brings forth much-needed conversations on how the internet shapes toxic standards and how cultural appropriation exists within the beauty community, by no means does this restrict individuals from appreciating cultures and trying out makeup looks. It does however, give us a basis as to what not to do when creating “new” fads.

Influencers and celebrities need to stop participating in harmful movements that rebrand POC cultures into trends that are exclusive to the white audience. Give credit where it’s due.

It’s time we ditch these toxic trends and instead stick with wholesome, unharmful dalgona coffee content.

This story was originally published on The Accolade on September 20, 2022.