Cornering the California drug trade

Courtesy of Amy Neville

Alexander Neville passed away on June 23, 2020, after consuming a counterfeit prescription pill he bought on Snapchat. Amy Neville, his mother, says this tragedy could happen to anybody.

October 18, 2022

Alexander Neville, an Orange County native, was 14 when he died of fentanyl poisoning from a counterfeit pill. Taking what he believed to be an oxycodone tablet supplied by a dealer he met on Snapchat, Alexander ingested enough fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, to kill four people. This dealer, who has been connected to the deaths of three other individuals, was just one cog in California’s state-wide illegal drug trade.

Through smuggling operations at the U.S. southern border, Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs) have imported massive amounts of illicit drugs into California. After they are transported to DTO affiliates, these drugs are widely circulated to various independent dealers, who then sell these substances to buyers through social media and in-person transactions.

Although the transport of illicit substances originates with DTOs, the California drug trade begins with the production of ingredients needed to manufacture drugs. Robert King, a prosecutor with the U.S. Attorney’s Office, who prefers to use a pseudonym to maintain his anonymity, says the production of raw materials for drugs begins with growing poppy seeds for the production of heroin, and the cultivation of coca plants for cocaine. However, King says that the production of fentanyl is more complicated.

Fentanyl, a potent drug originally created as a pain reliever for patients suffering from terminal cancer, contains various precursor chemicals. King says that once these chemicals (often manufactured by Chinese chemical companies) move overseas, DTOs use them to create this powerful drug. However, due to regulation from the Chinese government, the supply has tapered off over the past few years.

“The United States and the Drug Enforcement Administration worked with the Chinese government to get those compounds [controlled], and then the production seems to have dropped off, and is now largely done…by DTOs,” King said.

In addition to precursor chemicals, Chinese companies are also directly shipping fentanyl to various customers all over the world through transactions on dark-web platforms.

“When powdered fentanyl took off in the Bay Area, there were a fair amount of people who were ordering it from manufacturers in China over the dark-web and getting it sent to them,” King said.

Once the drugs are manufactured, DTOs begin the process of smuggling them into the U.S. Casey Rettig, a Community Outreach Coordinator for San Francisco’s Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) office, says the majority of illicit substances in California come through ports of entry at the U.S. southwest border.

“From [the southwest border], they’re parsed off into other organizations, so they can go to street gangs, or other DTOs operating in a different region,” Rettig said.

Although politicians claim the majority of drugs entering the U.S. are through undocumented ports of entry, this isn’t entirely true. According to the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, 90 percent of heroin, 88 percent of cocaine, and 87 percent of methamphetamine come from legal entry points into the U.S. Due in part to the busy nature of these stations, DTO affiliates often pass under the radar from border control agents.

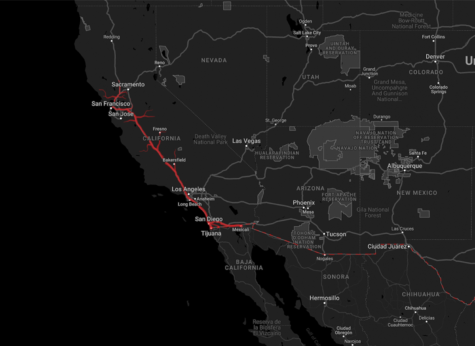

Once in the U.S., King says that smuggled drugs are often transported by interstate highways, the I-5 in particular. Along the way to Northern California and Marin County, the drug shipments make frequent stops.

“By the time [drugs] make their way to Marin County, it’s been handed off… a lot. [Drugs] get across the border in any number of ways, and then [they] generally come up I-5 and then it turns west [from] Modesto, Bakersfield, Fresno sometimes…, and it’s getting handed off from distributor to distributor along the way,” King said.

Once sold to independent drug dealers, illicit substances can then be sold through social media platforms. These drugs, particularly counterfeit pills, are frequently made with fentanyl in an effort to give users a stronger high, which may lead to possible addiction. Since the amount of fentanyl used in these pills is unregulated and inconsistent, they often contain a lethal dose of fentanyl.

“Alexander thought he was getting an oxycodone, [and] it turned out that it was a counterfeit made from fentanyl…and it killed him,” said Alexander’s mother, Amy Neville.

Amy Neville, a former yoga teacher, became an advocate for increased awareness surrounding the dangers of counterfeit prescription pills after her son’s death. Neville has spoken to various social media companies, particularly Snapchat, in an effort to prevent further fatalities from fentanyl poisoning.

“If I could have seen who this person was that Alexander had been communicating with, I would have known there was a problem…before things got really bad,” Neville said.

Neville says that in addition to communicating through social media, drug dealers interact with their clients in-person. Neville says that Alexander had met with his dealer a number of times.

“I know that this drug dealer that Alexander connected with through Snapchat probably delivered [drugs] to him right in front of our house. So [Alexander] had experience in seeing this person and talking to him,” Neville said. “I didn’t know that this was the drug dealer at the time, but Alexander made a comment about his ‘new friend’…and I was like ‘Wait, who is this new friend? Where do you know them from?’ You know, quizzing him all about this. After he died, I quickly realized that this person he had referenced offhand one day was the same person.”

According to Neville, other drugs such as cocaine or heroin are also laced with fentanyl. However, when it comes to pills sold on the dark web or on social media, Neville says many have lethal concentrations of fentanyl.

“I’ve heard from multiple youths, ‘Oh, my drug dealer would never sell me [fake pills], they would never do that to me.’ Your drug dealer has no choice in whether or not they’re doing that to you. They have no idea what’s in those pills…there is no such thing as a legitimate pill in the black market,” Neville said.

Despite the devastating impact of the California drug trade, advocates continue spreading awareness surrounding the dangers of drug use.

This story was originally published on The Pitch on October 13, 2022.