The Atlanta City Council approved a proposal to build a new police and fire training facility more than a year ago that would be developed on the site of the Old Atlanta Prison Farm. The site was dubbed “Cop City.”

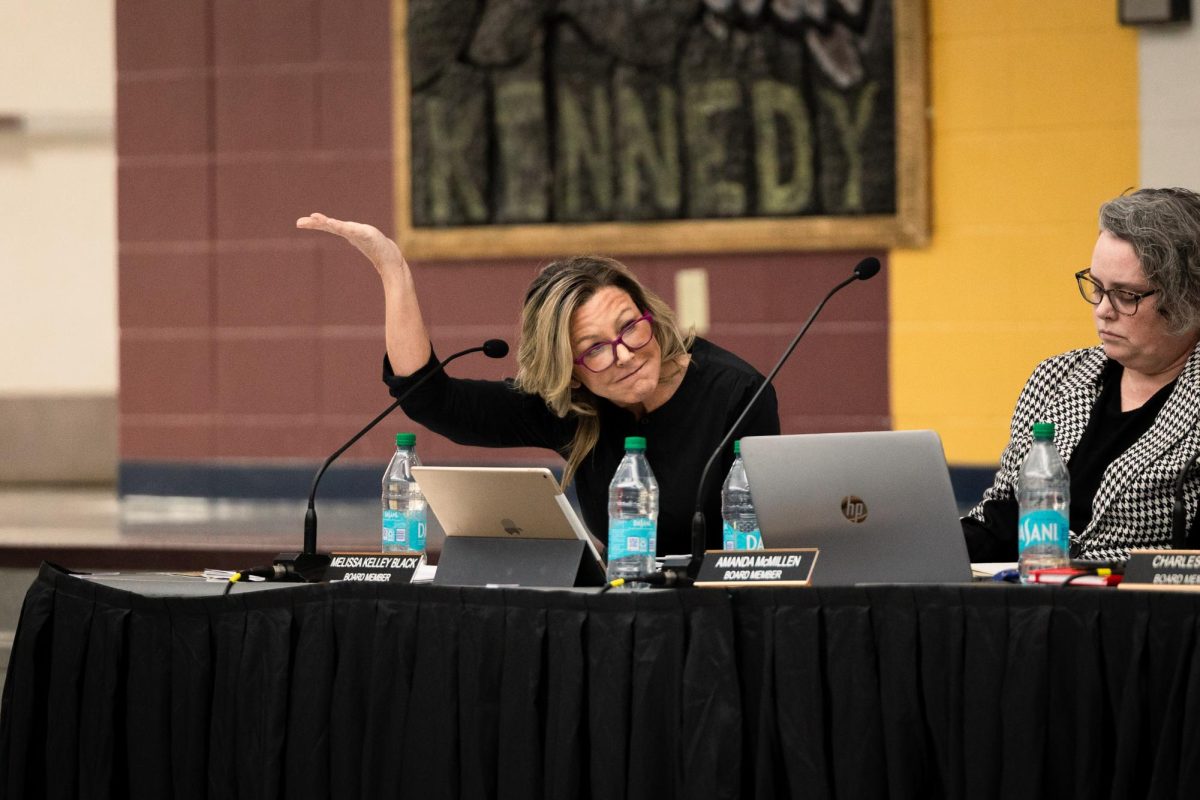

Despite 17 hours of public comment in which 70% of callers spoke against the facility, the council voted 10-4 in favor of the proposal. The forest, located on Atlanta’s Eastside along Intrenchment Creek, will house the $90 million training site and a Shadowbox film production studio.

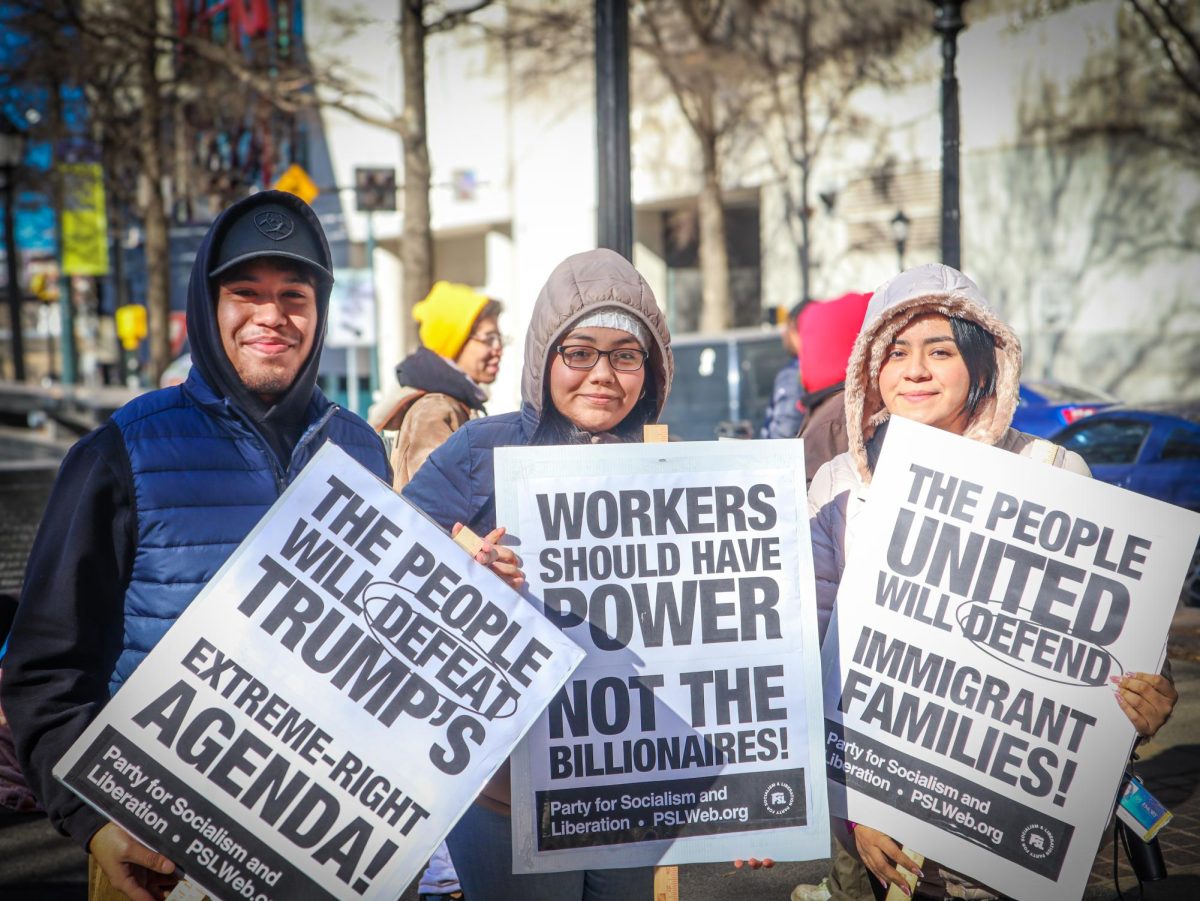

Since the facility’s approval, there has been outcry from the public against its construction. In opposition to development of the land, the Stop Cop City/Defend Atlanta Forest protest movement formed.

The goal of the protesters, who call themselves “Forest Defenders,” is to stop or delay construction on site. Dozens of protesters live in tents, treehouses and other shelters on the property in hopes of slowing the process. The efforts made have been met with police action, including arrests.

Sasha, whose last name will remain anonymous at their request, is a Forest Defender who has been an active member in the movement since the facility’s approval by the city council.

“I’ve been coming to the forest almost weekly, if not more, for the past year since the first week of action in June 2021,” Sasha said. “I initially learned about the forest through the movement. It used to be a prison farm, so I became particularly interested in that history. It seems it’s something everybody knows about the land, but hasn’t really thought about what it means for the fight.”

Sasha suggests the land’s history has influenced plans for development on the site.

“It seems to me very connected, the plan to build Cop City and that this land used to be a Prison Farm, a very brutal prison farm, in the 20th century,” Sasha said. “Since the farm closed, the land has been the most free it has been in 150 years. If they cut it down, again, and build a police academy, it perpetuates this form of policing and incarceration and domination of the city.”

One “Forest Defender,” who goes by the pseudonym “Rutabaga” in the forest, has been living on the property for 10 months.

“There’s so many layers to this project,” Rutabaga said. “The old prison farm used to be a plantation. Before that, it was stolen through colonization from the Muscogee people. It’s part of the continual legacy of racist colonial violence. I can’t get behind it, so yeah, I gotta get against it.” The Atlanta History Center has been contacted to verify this assertion, The Southerner is awaiting a response.

Sasha shared that the land increased her interest in Atlanta’s history and appreciation for the city.

“Coming here has taught me so much,” Sasha said. “Through coming back, I learn more about life in the city and its history. I think it’s important that this land exists so that more people can learn about the history of Atlanta by spending time in the forest.”

“Plum,” another Forest Defender who uses a pseudonym, has lived on the property off and on for two months. They previously worked with Line 3, a proposed pipeline expansion from Alberta, Canada to Superior, Wisconsin. Plum recounts encounters with police on the property.

“As of recently, most of it’s been on the old prison farm side,” Plum said. “They’ve been coming in with SWAT units and arborists and sometimes cutting down the tree sets or just going down the trees around it. People’s anchors were cut. There haven’t been many arrests because that’s not our intention here. With line three, that was kind of the goal: to get as many people arrested as possible.”

Despite difficulties, Forest Defenders have not backed down.

“The fight is on,” Rutabaga said. “There is so much momentum against this institution now. Just show up, just come down to the forest and check it out and see how you can get involved.”

If the movement succeeds, Sasha hopes the land will continue to be preserved and used for both education and remembrance.

“What I imagine is that this, the history of the prison farm, becomes more like public memory and public history of Atlanta.” Sasha said. “This forest could become a place that is almost like a memorial, a place to come and think about that history and memorialize the people who’ve been harmed by the city.”

The Forest Defenders are aware that their efforts might not succeed.

“There’s always a part of me that’s like, what if we don’t win, and having to cope ahead with living in a world where this might exist,” Rutabaga said. “I don’t think that it’s going to be the end either way. There will always be people who are going to resist these institutions, and they can’t win by killing our ideas.”

Plum said the key to the movement’s persistence is the people who participate in it. Forest Defenders encourage those new to the movement or who want to learn more to visit the property.

“I think a lot of it can seem scary, or it can seem intimidating,” Plum said. “But we’re all very nice. We will cook you food; you can help us take out trash; you can do water runs, not every task we’re asking people to help with is a really intense thing. No one’s asking you to burn down a bulldozer. We love people coming and hanging out and having a wider community than just us in the woods.”

Sasha also encourages the public to visit the land.

“I think anyone who’s interested or curious should just come and walk around and spend time here,” Sasha said. “I know it can be kind of strange, but I encourage everyone to just come anyway. Walk around and feel like, you know, this is a public park. You’re part of the public and anyone who wants to defend the forest can do so. Move respectfully and greet people, and you should feel very comfortable walking around.”

All Forest Defenders in this story were granted anonymity because of the nature of their protest.

This story was originally published on The Southerner on October 19, 2022.

![Girls wrestling captain Annalisa Afrifa holds a second place medal she won at the state championship meet her sophomore year. She wears medals she won at individual competitions. “It feels amazing to win,” Annalisa said. “It tells [me] that all my hard work hasn’t gone to waste.”](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Annalisa-1200x800.jpg)

![Some of the most deadly instances of gun violence have occurred in schools, communities and other ‘safe spaces’ for students. These uncontrolled settings give way to the need for gun regulation, including background and mental health checks. “Gun control comes about with more laws, but there are a lot of guns out there that people could obtain illegally. What is a solution that would get the illegal guns off the street? We have yet to find [one],” social studies teacher Nancy Sachtlaben said.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/DSC_5122-1200x800.jpg)

![NEW CHALLENGE, NEW TEAM MEMBERS: Every season, VEX creates a new game that robotics team members are faced with and have to build a robot to compete in. This year’s game forces students to create a robot that is able to stack rings onto mobile goals in order to score points. The change in games each season is something that robotics teacher Audrea Moyers appreciates.

“One of the things that I like about VEX is that they have a new problem to solve every year,” she said. ¨Even though the equipment’s the same, they have to analyze the game, and they have to come up with solutions that are unique that year. They are using their knowledge from prior years, but they have to kind of redesign a problem.”

As returning teams were faced a new game, some new teams and members had to adapt to a uncommon playing field and game.

“Three of our four teams were competing for the first time this year, and they had very different experiences match to match, so I think they learned a lot,¨ she said. ¨It’s hard just watching a video online to know how it’s actually going to be in person, so they all learned a lot about what gameplay is like, how to work with an alliance partner [and] how to adapt during the day to changes.”](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_9283-1-1200x800.jpg)

![French teacher Marieme Toure serves a plate of the Senegalese food she prepared for her AP French Language and Culture class, to senior Faiza Syed. “I never had Senegalese food before,” Syed said. “I thought it was so cool that she was able to bring a part of her culture [and] background to us.”](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/IMG_0798-1200x906.jpeg)