Do you know your rights?

Many teenagers do not know their rights or what to do in situations involving law enforcement.

Lila Vancrum

Officer Batley believes showing respect to an officer is the best thing people can do in any situation. “If you can be respectful and have a conversation with me, I’m going to do more to try to help that person in their situation,” Batley said.

November 14, 2022

“You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law.” These famous lines are part of your Miranda rights: the set list of rights police officers are required to recite when you are under interrogation or in custody, according to Overland Park Police Officer Jonathan Batley.

When those words are spoken, it likely ends the fun for teenagers who find themselves in precarious situations with the police.

Senior Adam Koehler proposed one reason teenagers may partake in illegal scenarios in the first place.

“I’m not an avid partygoer, so I haven’t been in a whole lot of [situations, but] the act of doing something a little bit illegal is the main enticing thing [for teenagers], I think,” Koehler said. “It’s almost that sort of ‘rebellious teen’ type of thing.”

In the past, Koehler found himself in a predicament where his peers had the possibility of getting in trouble with the police at a party. Though Koehler was not participating in anything illegal, he was fearful of being found guilty by association as he did not know the specifics of the law or his rights.

“It was scary, for sure. There was no panic, just a lot of uncertainty; nobody really knew what was going on,” Koehler said. “Then, when it finally set on us that, ‘oh, we’re in trouble here,’ that was when it kind of got really, really frightening. People were kind of losing their minds.”

Koehler thinks it would be beneficial for students to be more educated on their rights and the law. He said in the heat of the moment, many teenagers do not know their rights or what plan of action is best to avoid further consequences.

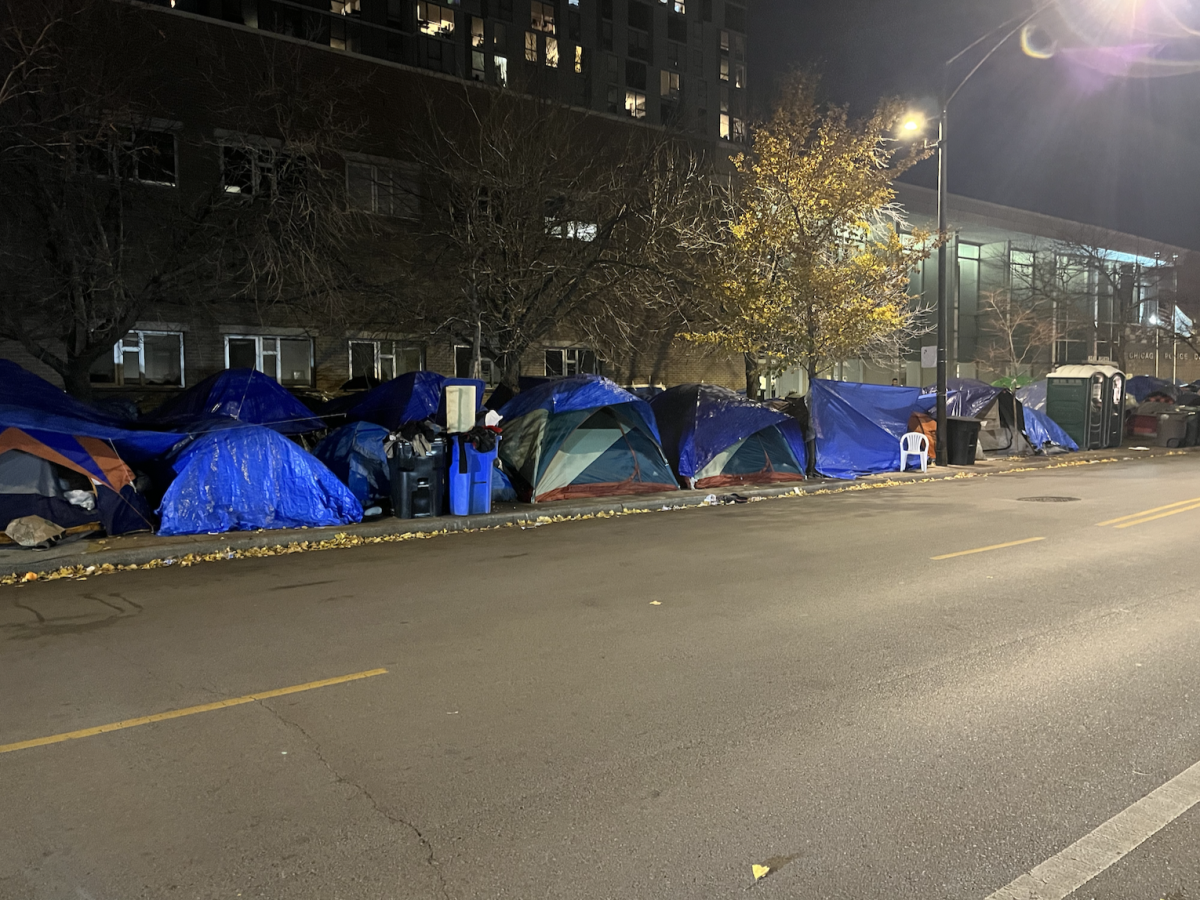

Say you are at an underage house party where alcohol, drugs or other unlawful substances are present and the police are called to come investigate. Batley said what an officer could charge a minor with in this scenario, which is similar to Koehler’s experience. Many minors think they can receive a MIP (minor in possession) or be charged with other misdemeanors, even if they did not consume any alcohol or drugs at the scene. However, Batley said this was a misconception.

“When it comes to things like alcohol and drugs at a party, there’s no law that says you can’t be around it,” Batley said. “The law says you can’t possess it, and you can’t consume it.”

However, Philip Glasser, a private practice lawyer in Overland Park, warned that in these specific cases, the officers may act subjectively. For example, if a minor is standing near something illegal, the officer may assume that it is in the student’s possession. This is why it is advised to try to stay away from these activities in the first place, even if you are technically doing nothing wrong, Glasser said.

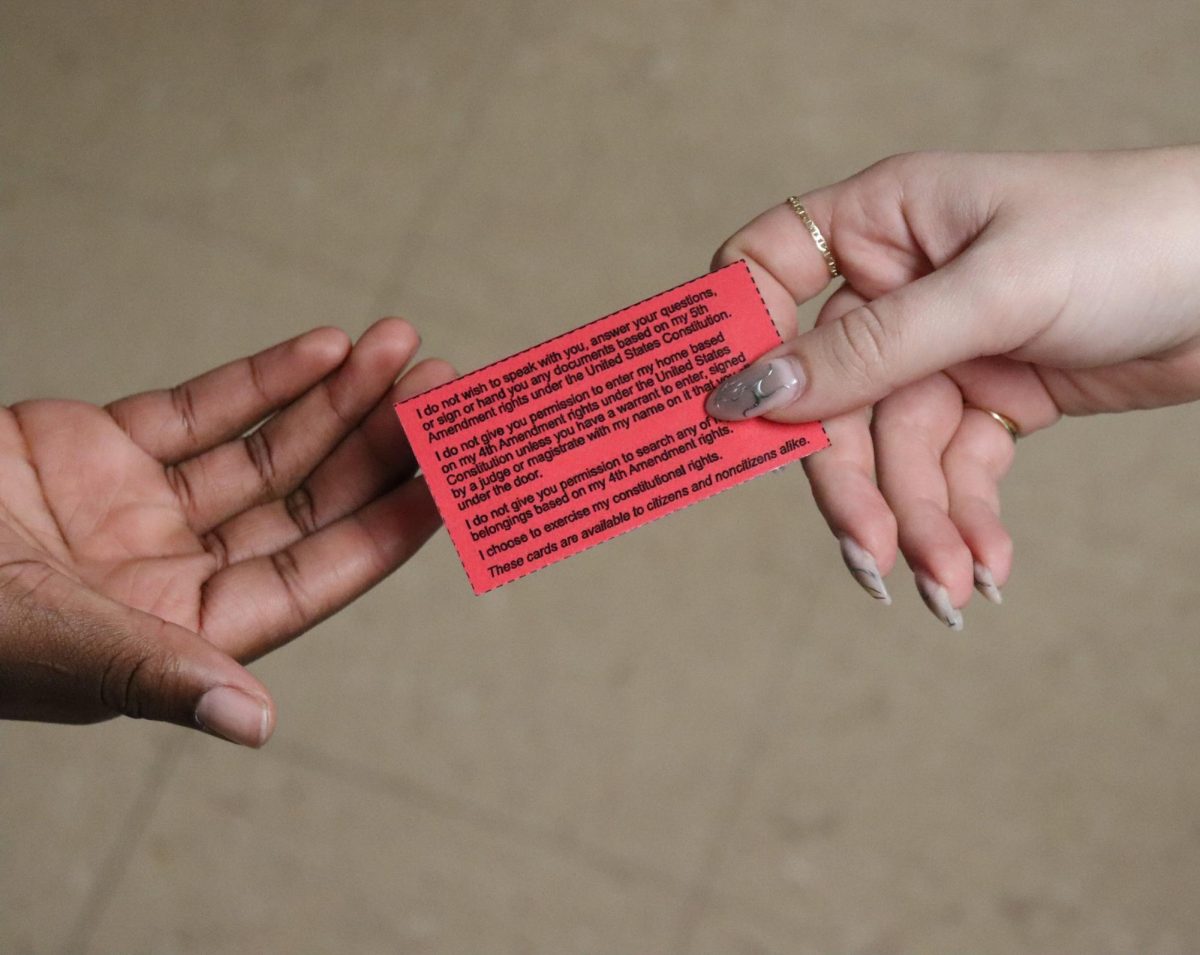

If the officer wants to come into the house where a party is going on, they usually need a warrant, but there are many exceptions, such as medical emergencies or destruction of evidence, according to Batley. He said the Fourth Amendment protects people and their property from unreasonable search and seizure by law enforcement or the government.

“Your rights are especially protected when it comes to your home,” Batley said.

However, to think it takes a judge days to get a warrant is a misconception. Judges anticipate warrant requests on weekend nights and can quickly send them to the officer electronically, according to Glasser.

“Judges are sitting there every Friday and Saturday night in Johnson County, waiting for those phone calls to come through,” Glasser said.

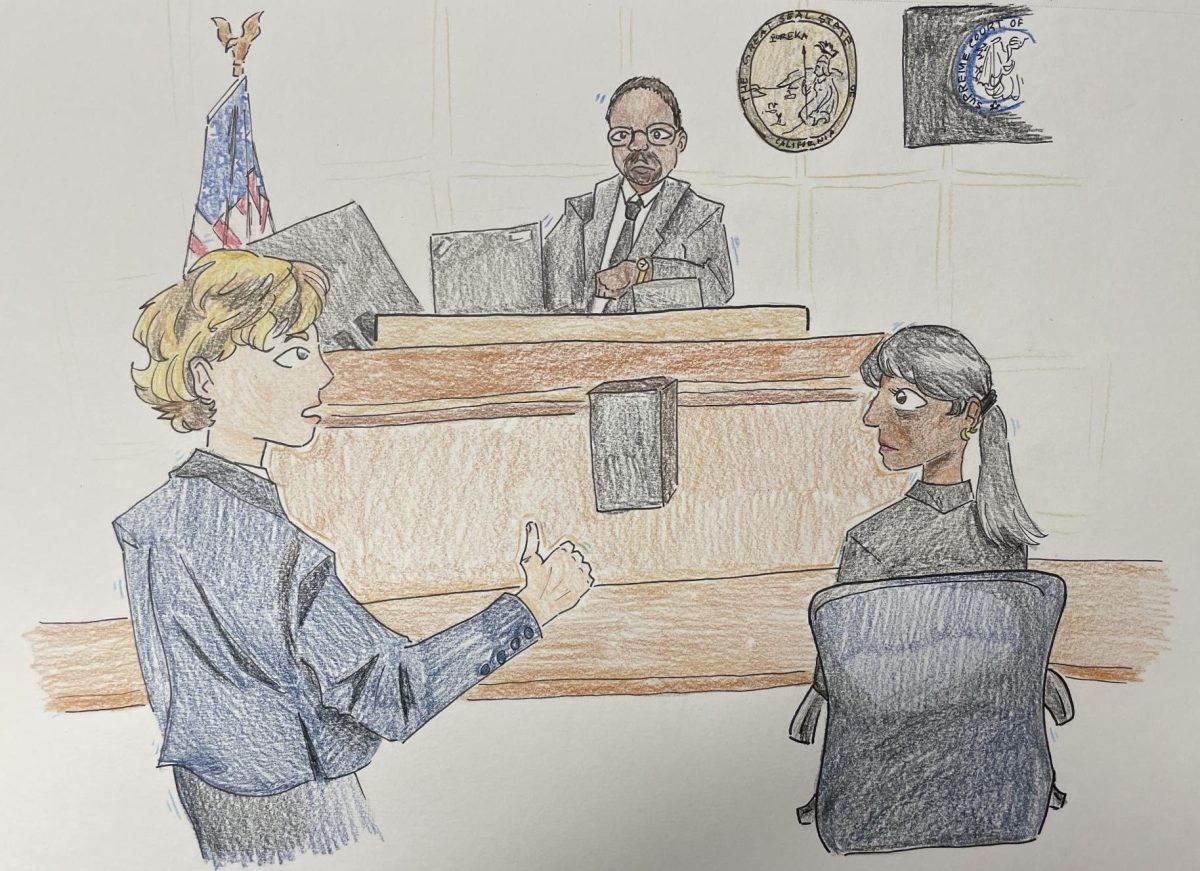

If events progress and an officer is interrogating you, Glasser said the Fifth Amendment grants individuals the right to remain silent and decline to answer the officer’s questions in order to avoid providing incriminating information against yourself. This means you may refuse to respond to an officer’s questions if they directly pertain to you. However, if you were trying to protect anyone else besides yourself from an incriminating charge, for example if you lied about seeing your friend drink, it would be considered an obstruction of justice.

“You can’t lie, and you can’t fail to answer a question when it’s [someone else’s] rights that are at stake,” Glasser said. “If I were their lawyer, I’d say ‘rat [them] out,’ because it will [benefit] you.”

Koehler said in these situations, being respectful and honest with officers can be your best plan of action.

“If you’re ever in a situation like that, no matter what kind of choices you have made throughout the night, the best thing you can do is to be honest and compliant,” Koehler said. “The worst thing you can do is try to run and get away, or directly lie to the officer. Most of the time, if you’re upfront from the get-go, nothing bad will end up happening to you.”

Blue Valley Campus Officer Cameron McLain agreed that the best thing for teenagers to do would be to simply comply with the officers, and the majority of the time, officers will be lenient and may not distribute any tickets. He also said giving multiple teenagers tickets causes a large amount of paperwork, which officers typically would like to avoid.

“My advice is just to be respectful. It’s not fun for an officer to walk into a house party with 30 kids. Imagine how much work that is, because they have to identify every single kid,” McLain said. “So if [an officer] walks in with 15 MIPs, that’s like a week’s worth of work.”

Batley said he understands how people get caught up in these situations, but he wants to clarify to students that often, it is just not worth it.

“So you go to a party that you think is just going to be friends hanging out, and all of a sudden, you turn the corner, and there’s a bunch of people pounding beers and smoking marijuana; that’s when you gotta make that decision. Am I going to stay here and be a part of this just by being around it, or should I not take a chance?” Batley said. “What are the consequences, and [are they going to affect me], or should I just go and do something else?”

Now, imagine you are pulled over on the side of the road by an officer; many teenagers may not know what to do in this situation. Glasser explained that you should have your driver’s license, vehicle registration and insurance ready to give to the officer. Glasser further explained you cannot refuse to provide such information, or else the officer will become suspicious.

“You’re obligated to have that stuff; that’s a lawful ask. That’s another reason for them to be concerned about what the heck is going on [if you do not give them what they are asking for,]” Glasser said.

However, citizens are granted the right to say “no” or refuse to interact with law enforcement under certain circumstances, Batley said.

“Anyone can always say no, but the only time it really holds legal authority is if the police are acting under the umbrella of consent,” Batley said. “So, if we’re dealing with someone who is consenting to us being there, they’re consenting to a search in a car. Whenever they say, ‘No, I don’t want you to do that,’ then we have to stop.”

Glasser elaborated on when individuals can say “no” to law enforcement regarding car situations.

“Under Kansas law and federal law, you don’t have to say yes; you can say no. They may still have a reason that they can use to search without your consent, but it is possible to withhold consent on a search for an automobile,” Glasser said.

Batley explained they are allowed to search a car if they have reasonable suspicion. An example of this would be smelling the odor of marijuana or seeing evidence of alcohol. McLain said if an officer suspects you will endanger someone, or if alcohol has been involved, they can subsequently take your keys.

“If [I am] fearful that they might drive away, I might just say, ‘hey, give me those keys,’ because I’m worried they might take off on me,” McLain said.

In most cases, McClain said he believes officers want to act as an educational resource instead of trying to catch teenagers in the wrong and punish them. He said officers value students’ safety and overall future above everything else.

“I feel like everyone thinks officers are out to get them, and we are not,” McLain said. “I would rather every kid make the right decision, do the right things, and have the best opportunity to move forward after high school.”

McLain said he believes it is much more beneficial for minors to learn from their mistakes in a teaching manner, rather than having something on their permanent record.

“[We] want to see you guys go on and play sports in college, or go on and get scholarships,” McLain said. “But if you get arrested for every little thing, then you quickly lose those opportunities.”

Similarly, Batley said officers prefer to have schools or parents handle the consequences, rather than the courts, in order to not completely damage a teenager’s future.

“A lot of courts are trying to minimize juveniles’ experiences in the criminal justice system, so that’s one reason why we release them to their parents and don’t take them to a detention center,” Batley said.

Koehler elaborated on this idea, speaking on how some of the punishments due to naive mistakes can have heavy repercussions. For instance, if a school hears about a problem, the student could be kicked off of their sports teams or exempted from their extracurricular activities.

“Some of those [charges] can be pretty serious and ruin your whole year,” Koehler said.

Batley emphasized the idea of thinking about future consequences before you act, and implores teenagers to incorporate this type of thinking into their lives.

“Before you make a decision, before you go somewhere, before you get involved in something with potential [negative] consequences, make an informed decision about what you’re doing,” Batley said.

This story was originally published on BVNWnews on November 4, 2022.

![Finishing her night out after attending a local concert, senior Grace Sauers smiles at the camera. She recently started a business, PrettySick, that takes photos as well as sells merch at local concert venues. Next year, she will attend Columbia Chicago College majoring in Graphic Design. “There's such a good communal scene because there [are] great venues in Austin,” Sauers said. “I'm gonna miss it in Austin, but I do know Chicago is good, it's not like I'm going to the middle of nowhere. I just have to find my footing again.” Photo Courtesy of Grace Sauers.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Grace.png)