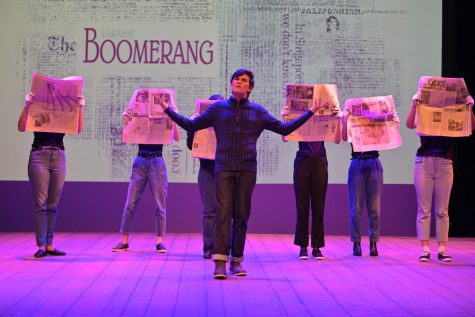

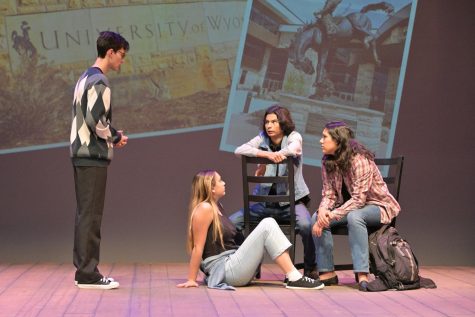

The Performing Arts Department opened the fall play, “The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later,” to audiences in Rugby Theater on Oct. 28, 29 and 30. The show centers on how the community of Laramie, Wyoming grappled with the murder of Matthew Shepard in an infamous hate crime that took place in their town ten years prior.

In October 1998, Matthew Shepard, a gay college student attending the University of Wyoming in Laramie, was brutally beaten and left to die on the outskirts of the town. The hate crime received international attention and an outpouring of grief, leading the Tectonic Theater Project to travel to Laramie and interview residents of the town impacted by Matthew Shepard’s murder. The result of the interviews was “The Laramie Project,” a play that examines the town’s reaction to the murder and the implicit hatred that enabled the crime to occur. Written a decade later, “The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later” is the sequel to “The Laramie Project.” “The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later” examines how Laramie residents made excuses to avoid dealing with Matthew’s murder and how hate, ignorance and the spread of misinformation can mold a community.

In an interview with The Chronicle, Judy Shepard, Matthew Shepard’s mother, said performing “The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later” provides a unique and impactful educational experience.

“It’s a life-altering experience for everybody who participates in this [play],” Shepard said. “I don’t think they realize when they take it on [that] it educates folks in a way that I don’t think they expect. It still engages some level of controversy in communities, so I am very proud of anyone who takes it on because it can be a challenge.”

Clara Berg ’25 played Marge Murray, the mother of the police officer who found Matthew Shepard after he was left to die. Berg said she thinks it was an important choice for the school to put on “The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later” because it serves as a reminder to the school community that Matthew Shepard’s story is still relevant.

“I think this show is significant because it’s different from plays that are usually done at a school,” Berg said. “This was an important show to do because of its heaviness and the reality of it. Because Matthew was killed in 1998, some people find it easy to just think of it as something in the past that is not important today, but this play and its message show how Matthew’s story is still present and relevant now. This play has brought me new awareness, especially being queer myself. This play educated me, and connected me with Matthew, his community and my community.”

Both shows use verbatim theater, a form of documentary theater that uses the exact words of real people collected during interviews. The school previously put on productions of ‘The Laramie Project’ in 2005 and 2012, both directed by former Performing Arts Teacher Ted Walch. This year’s production honored Walch on the ten year anniversary of his final production of the show.

Performing Arts Teacher and Director Michele Spears said the story was chosen because of its connection to current events and Walch’s love for the show.

“In truth, ‘The Laramie Project’ was on my list for a while, but then I reread the ‘The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later’ and it felt like it better reflected what’s going on today,” Spears said. “There was another layer in Ted Walch, who founded [our] theater program. By the time we were in discussion about what play to do, we knew that he was dying. [Both shows] were very important to him and a very significant part of the program’s history, so doing the second play felt like a collaboration in answer to him and what he brought.”

Weston Fox ’24, who played Tectonic Theater Project member Moíses Kaufman and Laramie resident Jonas Slonaker, said the story brings attention to the issues of hate, misinformation and the oversimplification of complicated events.

“This show feels really significant right now, because there is so much more hate in the world, and the simplification of events is doing incredible harm to how stories are perceived in general,” Fox said. “This play is working to bring light to those issues, [showing] how these problems have not gone away, [but] they’ve just been pushed out of the public view.”

Spears said it was difficult to do justice to the true story, but students managed to persevere through these challenges.

“The weight of it was a challenge because we’re asking young people to open themselves up to these things that I hope, for the most part, nobody has ever had to bump up against,” Spears said. “But as an actor, that’s your mission, to step in and understand all sorts of people in order to serve the story that’s being told.”

Emily Malkan ’23, who played Tectonic Theater Project member Stephen Belber and friend of Matthew Shepard Romaine Patterson, said it was difficult at first to step into the lives of real people, but as she grew to understand her characters’ emotions, the process became easier.

“It was definitely a unique experience doing a verbatim play,” Malkan said. “Even though my characters were real people, they still felt somewhat distant to me in the beginning because we are different, but I related with the characters more when I understood what they were feeling and what caused them to say what they did say.”

Fox said while it is easier to portray a fictional character, the opportunity to play a real person provided unique opportunities as an actor.

“[Acting as] a fictional character, you do almost anything [because] you only get the lines,” Fox said. “But with Moisés and Jonas, there is so much more to explore. The words that are seen reflect so much more emotion and power than what a fictional character could say, as they’re rooted in reality and [are] much harder to ignore. The whole process had a greater weight to it because I’m trying to show two people, not just two characters. I can’t just copy them, but I need to honor who they are.”

Roles were open to students of all identities, regardless of the character’s actual gender, race, religion or sexual orientation. Spears said every student who auditioned received a part. Assistant Director Zoe Shapiro ’23 said an additional challenge for actors was portraying characters whose actions and opinions they may disagree with.

“Another element for actors was playing a person that’s still alive and not thinking of them as a villain, even if they don’t agree with their views,” Shapiro said. “All these people have depth and I think that was a big challenge for people to explore their characters and understand there [are] so many layers.”

Nathaniel Palmer ’24, who played Laramie resident Jeffrey Lockwood, police officer Rob DeBree and Matthew Shepard’s murderer Aaron McKinney, said while it was difficult to step into the role, fully understanding how other characters viewed McKinney enabled him to better portray him.

“Getting into the role of Aaron McKinney was initially pretty difficult,” Palmer said. “At some point, I put Aaron on the back burner and focused on my other characters, namely Rob DeBree, who hates Aaron. Strangely enough though, being in that mindset of hating my own character helped me to form Aaron. Whenever I played Rob I thought ‘What kind of a person could be so monstrous that this jaded old cop is showing his anger?’ and I realized it was my job to tell the audience.”

Along with the cast of 20 actors, a technical theater group helped stage manage and design and run the lighting, video and audio for the show. Additionally, a team of student musicians composed music for various scenes throughout the show.

Dramaturge Sylvee Anderson ’24 participated by researching the incident for the company throughout the rehearsal process. Anderson said she learned from the play that it is important to understand the full depth and motives behind peoples’ actions.

“One thing I took from researching [the incident and these people] was that people who do bad things don’t come out of a vacuum,” Anderson said. “That’s not to say you excuse them for it or say it’s ok, but it is important to understand what leads people to do what they do and why.”

Like Anderson, Palmer said the play showed him the important context in understanding peoples’ actions, and that education has the power to make a difference.

“What I took away from this play is that everything in the world can change a person,” Palmer said. “Everything has an effect, and I hope that’s what audiences took away, too. Bad people are not these monsters who just appear from the darkness and commit atrocities, they’re just people who are misguided. Aaron McKinney was not some bloodthirsty animal out to kill for sport, he was a man so unbelievably misguided that he truly believes that the solution to the problems he saw was to kill. What people need to see and act upon is that those things can be stopped, not by someone being more observant or acting more drastically against perpetrators, but by educating people.”

Spears said while the play wasn’t necessarily uplifting, the impact it has on audiences is what makes performing it meaningful.

“People confessed to me in honesty that they dreaded having to come and see this deep play with young actors, but after they [said] we handled it beautifully,” Spears said. “That’s our point. The audience connection is the thing that makes theater different [from] anything else. That conversation with an audience and that impact that you feel in a room when an audience goes still, that is the special purview of the medium of theater. So I think we achieved that really beautifully with this show.”

Fox said the play was personally impactful and he hopes it inspired audience members to similarly embrace the messages within the show and create change.

“For me, the play was so inspiring,” Fox said. “There are so many different lessons throughout the play, and I hope the audience recognized them. Because we shared this story, the audience became a part of it and they can help bring about change and spread the messages of ‘The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later’ even farther.”

Shepard said she thinks “The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later” is especially significant because of its universal lessons about hate.

“I’ve always thought the really important part of [both plays] is if you remove Matt and his sexuality, and then introduce [any] religion or race, it’s the exact same story about prejudice, ignorance and hate,” Shepard said. “It introduces that concept to students, but also the idea that everybody comes from different backgrounds and perspectives. We need to take that into account when we talk about these stories, and try to educate and open their hearts and minds to the idea that we’re all just people.”

This story was originally published on The Harvard-Westlake Chronicle on November 16, 2022.