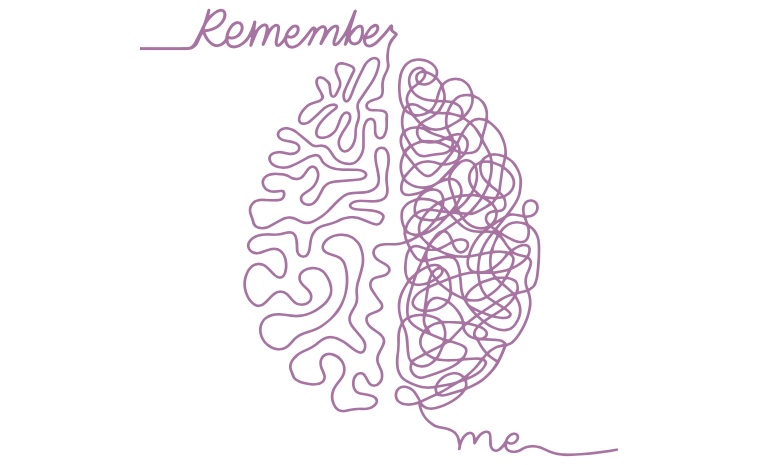

Remember me

Dementia and Alzheimer’s affect family dynamics at various stages of life.

Sabrina San Agustin

Digital illustration depicting one half of a healthy brain and one half of an Alzheimer’s-induced brain.

January 10, 2023

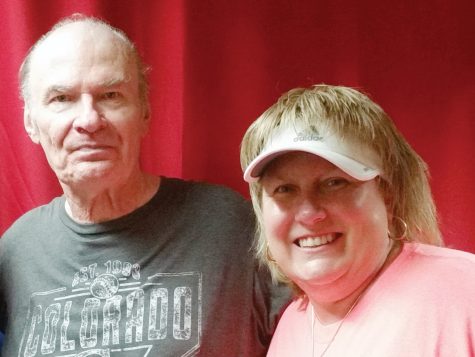

Broadcast teacher Kim White has long-feared her own diagnosis of Alzheimer’s since her father developed the disease.

“What if I’m the one that has [Alzheimer’s], who then takes care of me. I don’t have kids, I’m not married. So, there’s a part of me that’s a little bit scared and worried. What if I’m next?” White said through tears.

White’s father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s almost nine years ago and now lives in an Alzheimer’s care facility in Overland Park. White’s aunt also had Alzheimer’s, and her grandmother had dementia.

Neurologist Jeff Burns co-directs the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of Kansas Health System and practices at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

Burns said Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia. He defines dementia as, “memory and thinking changes that interfere with daily function…Alzheimer’s is the most common and it’s defined as the presence of plaques and tangles in the brain,” Burns said. “[Those affected] tend to have short-term memory problems and other cognitive problems with organizing and planning. They don’t have any problems with their movements and their motor systems.”

The changes Burns described were familiar to White as she recalled her cousins talking about the symptoms of her aunt, and she said it sounded similar to what her father was experiencing. She flew down to where her parents lived in Georgia and was shocked when she saw the state her father was in.

“I was surprised because my dad is a really strong man, and he was just an entirely different person. His language changed, his mannerisms changed, the way he acted changed,” White said.

“When he was finally diagnosed, it wasn’t like an initial shock, but rather kind of validating that my suspicions were real,” Masterson said.

Mickey also said there was no “initial shock” when he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s because his father, uncle, cousins and sister have all been diagnosed.

“I wasn’t quite shocked, because of the fact it was a kind of a family trait,” Mickey said.

Masterson described how her family changed after their suspicions were validated.

“We didn’t really talk about it to each other, out of respect for my dad and his privacy. You could definitely tell that everyone was kind of upset about it, but we didn’t say anything really out loud in a group to each other,” Masterson said. “You might have said something one-on-one to somebody but it was just a touchy subject within my family.”

Likewise, Burns said this disease can interfere with relationships because of its side effects.

“They aren’t able to do what they used to do as well; they often respond by feeling down or depressed, which influences relationships with others,” Burns said.

BVNW parent and co-founder of Prairie Elder Care Michala Gibson said there is a loss of control many families experience.

“The control is taken away from the [person] and the family, and they are left with a sense of helplessness, and they don’t know how to fix it. It is like the rug has been pulled out right under their feet,” Gibson said. “[At Prairie Elder Care,] we try to give them as much control as we can that most people try to take away. It gives them a higher quality of life and reason to live.”

White explained her family did not tell her father he had Alzheimer’s to help him retain his sense of hope.

“All the research I’ve read, all the people I’ve met, all the people I’ve talked to say that once an Alzheimer’s patient knows they have it, they give up because there’s no cure,” she said.

One of the most challenging things about being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, Mickey said he has endured, was having to make the adjustment at work. Mickey was the Athletic Director at Blue Valley North for 12 years, but he was unable to work after he was diagnosed.

“I went from making a good amount of money to not being allowed to do it and not having any ability to work,” Mickey said. “I have a good family and people that support me, but, you know, for my whole life, I wanted to support my family. [And now I] can’t do that.”

Masterson said it has been hard for her dad to participate in certain family activities since his diagnosis.

“There are lots of games that we always play at our holiday parties. We love card games, and we’re all really good at them. But since he can’t deal with numbers, he is unable to play [with us] anymore,” Masterson said.

White explained what has helped her father the most is time with his family.

“When I first moved my dad here, they told me he had two to three years to live. That was really hard to hear. Now we are almost nine years later, and he’s still with us, that’s amazing,” she said. “The doctors and the nurses say the reason they believe he’s still here and he’s still doing as well as he is, is because we spend so much time with him.”

White explained how her relationship with her father completely changed from what it was before.

“My dad’s always been my rock, so I feel like that role has kind of reversed. I feel like I try to be there for him, the way he’s always been there for me,” White said.

Although her relationship is different than it was before, there are still some things that have stayed the same.

“We still watch a lot of ball games together, especially on Sundays; we catch the Chiefs when they play at noon. I stop at McDonald’s and get him a sweet tea and an apple fritter and his eyes just light up,” White said. “But it’s just different; I used to have a lot of heart-to-heart conversations with my dad about life, about family, about sports, just about a lot of things and his mind just doesn’t process.”

Masterson also expressed concerns about how quickly her father’s condition would worsen and how her relationship with him may be affected.

“[I worried about] how long he’d really be my dad. Since I’m the youngest, I was worried that I would be the first to go [from his memory], and that it was going to be a super rapid decline,” Masteron said.

When it comes to keeping himself healthy, Mickey said he has never had any struggles in terms of denying he has the disease. He often tries to get out of the house and stay active.

“One of the things that helps me is I referee basketball. So that helps, at least to get me out so I’m not just hanging out at home all the time,” Mickey said.

Mickey is going through day-to-day life as Burns described is best to keep spirits up.

“I think recognizing [that they’re] vulnerable and really trying to acknowledge that they’re not dumb. They’re not. This is a disease.” Burns said. “What [they’ve] got to do is try to maximize what [they] have, make sure [they are] on the right medicine and make sure [they’re] exercising and staying active mentally and physically.”

Burns not only gave advice for the person with Alzheimer’s, but also their family members and loved ones.

“Be understanding by not picking fights and not trying to win fights with people with Alzheimer’s because their ability to reason through problems isn’t as good as it used to be. It’s not worth arguing over most things, so just pick your battles,” he said.

Burns also advised family members to note the disease may affect the things they say.

“Try to have thick skin because one day they may be happy and nice and then irritable and angry. It’s not personal. It’s the disease,” Burns said.

White has endured difficult experiences like this but she reminds herself it is not her father but it is the disease.

“Those bad days are hard because the person in that body is not my dad. He says things and that can be just gut wrenching. He’s hateful sometimes, and some of the stuff he says hurts a lot,” White said. “But I know that that’s my dad, and that’s what gets me through, is the days where I get to talk to my dad.”

Masterson said she also struggled when trying to spend time with her father after his diagnosis.

“There’s kind of a war going on inside your head between wanting to spend time with them, and when you are [actually] spending time with them, having to hold it together,” Masterson said.

Gibson said the good and bad days can be conflicting for the family to go through.

“It is hard to watch someone you have known and loved deteriorate. I do always say on the bad days remember the good days. The bad days can be harder for the loved ones than the patient, but the good days can be so rewarding,” she said.

Burns added that taking care of someone who has never needed that before can be difficult for the family.

“The hardest job for anybody is being a caregiver. Nobody’s prepared for it. Nobody feels up to the task,” Burns said.

White said that her mom’s emotions have taken a toll on her due to the duties of being a caregiver to her husband.

“One of the hardest things for me to watch is my mom watching what’s happening to my dad. She’s losing the man she loves and has been married to for 50 some years, so watching her have to watch him decline has been hard. She’s done it as best as she can and she’s been a trooper,” White said.

Although Masterson said she sometimes struggles with this, she reminds herself who her dad really is.

“Nothing has changed. He’s still that same person in my heart and everybody else’s hearts. The disease does not impact the way we see him,” Masterson said. “We still love to spend time with him, no matter how hard it is. He’s our dad.”

Masterson feels that the outside world views those with Alzheimer’s differently from reality.

“I think a lot of people, when they hear that [my dad] has Alzheimer’s, they assume that he can’t really remember anything at all,” Masterson said. “But, because of his medication, he remembers a lot of things, right now.

Mickey added another challenge he faces is communication and numbers.

“I know what I want to say, but I just can’t get the words out. It’s really frustrating,” Mickey said. “I cannot figure out my numbers. When [doctors] say to me, go backwards on numbers, I’m like, ‘wow, yeah, that’s really really hard for me.’”

Looking back, Masterson realized talking more about this subject would have helped her, rather than going through it alone.

“I definitely would not advise someone to go through this alone. It’s really hard to process on your own because you’re losing them, but you’re not,” Masterson said. “They are there, physically, but their brain is unable to associate the things that they love to do, with the ability to love to do those things. They don’t necessarily know who they are as a person anymore because they can’t make those connections.”

Although Mickey is in his early stages of Alzheimer’s, Masterson said it will get to a certain point where he might not remember her.

“When you get late in your diagnosis, you stop being able to associate the people with the connections,” Masterson said.

Mickey’s wife, Xenia Masterson, said he is in the process of possibly being admitted into a study which is looking to help slow the development of Alzheimer’s.

“They’ve already kind of discovered what is helping slow down Alzheimer’s, but [they are] trying to figure out how to slow down the Tau that builds up in the brain because they think that the brain connectors are not connecting for memory,” Xenia said.

Tau is a protein found primarily in neurons, or brain cells. Its main function is to stabilize microtubules, thus allowing cell and mitosis to function efficiently. However, if Tau acts abnormally it then creates tangles within the neurons, thus inhibiting basic brain functions.

Mickey said his biggest piece of advice he would give to people dealing with Alzheimer’s is to be patient and have hope for the future.

“There’s a lot more out there. In terms of things that they’re doing now [that] they weren’t doing ten years ago, five years ago, even,” Mickey said. “A lot of research says that there’s some breakthroughs coming, and I obviously think that’s a great thing.”

Mickey also said he would advise getting involved in a study.

“Get with a study. Because again, there’s this ability to not only have something going on for you, but you also are there and people are checking on you constantly,” Mickey said.

Aside from the daily challenges Alzheimer’s brings, Mickey’s biggest motive to keep going is the desire to benefit the future generations.

“My goal is to help somebody down the road; whoever has [Alzheimer’s] and then hopefully we can find a cure,” Mickey said.

This story was originally published on BVNWnews on December 19, 2022.