At the center of ‘the drug triangle’

For McHenry County, opioid deaths and overdoses are not a far-away problem, so who and what does it take to keep the epidemic at bay?

Allie Everhart

People living in McHenry County have struggled with addiction during the opioid epidemic. Some say chains like Walgreens and CVS have made the problem even worse.

January 19, 2023

It takes a village to combat an epidemic, and McHenry County is no stranger to that.

Like much of the United States, McHenry County is grappling with the effects of opioid use. In 2022 alone, the county lost around 20 lives to opioid overdoses, per McHenry County Department of Health data.

What led to a skyrocket in opioid deaths in 2017 is unclear and a complicated research question. There were around 24 deaths per 100,000 people that year, compared to 13 just two years prior. At the time, the county was in the top five for most opioid overdose deaths.

A possible explanation is McHenry County’s unique location at the center of Chicago, Milwaukee and Rockford — what experts call “the drug triangle” because of easy drug access through connected highways.

To this day, McHenry County maintains moderately high numbers of fatal and non-fatal overdoses.

The term “opioids” refers to the entire family of opiate drugs, which can be natural or synthetic. Some, like oxycodone and Vicodin, are prescribed following surgeries or health conditions like cancer. Others, like heroin and fentanyl, are obtained illegally through drug dealers.

Both synthetic and natural opioids work similarly — they attach to opiate receptors on nerve cells and block pain messages from reaching the brain. Because of this, opioids can be highly addictive, as people enjoy the euphoria.

With prescription opioids, addiction occurs by taking medication in a way other than prescribed, taking someone else’s medication or taking it with the intention of getting high.

That is how the nationwide epidemic came to be; pharmaceutical companies in the 1900s assured patients they would not become addicted. At the time, they didn’t understand the effects opioids had on people. Today, over 10.1 million people in the United States misuse opioid medication and over 1.6 million have an opioid use disorder.

Illinois, along with several midwest states, was cited as one of the states with the highest drug overdose rates in 2020, with 3549 deaths.

Together, local government entities and community organizations seek to keep the opioid epidemic at bay. Through policies and resources, they aim to lower opioid-related overdoses and deaths that have taken many lives from McHenry County through the years. This is their side of the story.

The families

Junior Kyle Stojak was only in the 7th grade when his cousin died after struggling with opioid use. Stojak had known him for a long time and recalls hanging out with him at family gatherings.

“I was on my way home when I FaceTimed with him while he was lying in the hospital bed, unable to speak,” he said. “A couple of hours later, he didn’t make it. It was detrimental at the time.”

Stojak notes that while his cousins were using opioids, they became more financially unstable and careless with their decisions and actions — an experience shared by many families of people with addictions.

“[My uncle] stole my dad’s car radio to get money to purchase drugs,” a senior, who wished to remain anonymous for privacy reasons, said. “Since his passing, my grandparents still haven’t gotten over the fact that he’s gone.”

Both students mentioned that when their respective family members died, they left behind many loved ones. Now, those individuals are coping with their father, uncle, boyfriend, son or grandson being gone.

“My uncle had an overdose and passed away,” added the anonymous senior. “He left his child and girlfriend. It’s hard seeing my cousin grow up in a fatherless household.”

Often, society considers substance abuse disorders moral failures rather than medical conditions. Because of this, both people with substance abuse disorders and their families tend to avoid discussing their struggles.

“When I was younger, I found it hard to discuss [my family’s struggles],” the anonymous senior said. “I thought people would judge me. I thought people would be like, ‘Oh, so that runs in your family? Maybe you partake in that stuff, too.’”

A person’s decision to seek rehab or help often depends on the treatment they receive from society and loved ones. Thus, the stigma surrounding substance use tends to harm those struggling, noted the students.

“Society should go out of their way to help those with issues,” Stojak said. “Many people will refuse to seek rehab, like … my uncle, for example. Not taking actions is not going to solve the problem by itself.”

Loved ones of people who died or are struggling with opioid use need support, too, notes the anonymous senior. Seeing family struggle can take a toll on them, so help from the community means a lot to those affected.

“Honestly, just be there for them,” they said. “Help them out. If you can, be a shoulder to cry on. Be a person that they can talk to about their struggles and hardships.”

The state’s attorney

The McHenry County State’s Attorney office first noticed opioid-related deaths skyrocket in 2017. Upholding public safety, the office implemented policies to hold drug dealers and those who share drugs accountable that same year.

“We became the most aggressive county in the country with prosecuting drug-induced homicide,” Assistant State’s Attorney Brian Miller, who supervises drug prosecutions, said. “That’s part of the approach we’ve taken locally.”

Almost six years later, McHenry County continues to track several opioid-related deaths and overdoses each month. Attempting to get accountability, State’s Attorney Patrick Kenneally filed a lawsuit this August against pharmaceutical companies for their alleged role in the epidemic.

“

Particularly, we joined [the lawsuit] because the opioid epidemic … is not just a far-away problem,” Miller explained. “It’s a problem that’s hit close to home here in McHenry.”

The original lawsuit aims to hold opioid manufacturers and distributors accountable for profiting off medications in a way that contributed to the United States’ growing opioid epidemic. Specifically, it claims there was little oversight and regulation when filling opioid prescriptions.

“That’s not the sole cause of the opioid epidemic by any means,” Miller said. “It’s a multifaceted problem with many causes. We’re trying to address [it] as best as we can, so this is just one way we’re fighting [for] accountability.”

Pharmaceutical companies could not comment on their practices due to pending litigation.

Miller added that several lawsuits against Walgreens, Walmart, CVS and other big-name pharmacies are still ongoing. McHenry County has had previous success in one of these opioid-related suits.

“There’s a massive settlement … in which McHenry County got approximately 3.4 million dollars,” he said. “Although, that’s paid out over the years, so [immediate] compensation is somewhat smaller.”

Meanwhile, the State’s Attorney Office continues a multifaceted response to the epidemic. McHenry County works closely with the Substance Abuse Coalition and other community-based organizations to brainstorm ways to combat the crisis.

“We’ve also implemented, to the best of our ability, strict terms to probation for addicts — requiring drug tests weekly, in addition to rehab or other monitoring,” Miller added. “We really want to be involved; we need to keep a close leash. Opioid addiction is very, very hard to overcome.”

Unprecedented challenges along the way include Illinois’ proposed House Bill 3447. The bill would make possessing specified amounts of opioids and other drugs Class A misdemeanors instead of felonies if passed.

“Our office is opposed to it,” Miller said. “I don’t want to speak completely on behalf of Mr. Kenneally, but I will say that we don’t see that removing penalties for drug possession is going to help addicts in any way.”

He added that the potential of a felony functions as a deterrent to keep individuals from using or selling opioids. Felonies come with prison time and hefty fines. In contrast, misdemeanors typically come with a fine not exceeding $2,500.

“In our experience, people have not willingly gotten the help they need,” Miller said. “Some do. But, people get into treatment because there’s the penalty of incarceration.”

Though there are challenges, the State’s Attorney Office constantly brainstorms and discusses appropriate responses to help those with substance use struggles.

“I can say that our office is very sympathetic to the tragedies that occur in our community with regards to drug addiction and overdoses,” Miller said. “We don’t get it right every time, but … we’re trying our best to make a difference, fully acknowledging that the solution is not going to end with our office.”

The department of health

To keep McHenry County informed, the Department of Health releases an “Opioid Surveillance Report” monthly. It details emergency department visits and opioid overdoses, along with data on the race, ethnicity and age of those affected.

“IDPH and CDC have presented data that suggests overdoses increase in the holiday season due to stress,” Epidemiology Lead Ryan Sachs and Prevention and Response Lead Chrissy Wasson wrote in an email. “This could potentially explain the recent increase … however, we [can’t] determine if this is the exact reason.”

In McHenry County, overdose deaths predominantly occur among males aged 20-29 who identify as non-Latino or Hispanic white. Many substances contribute to the epidemic locally, but one, in particular, contributes to overdoses the most: fentanyl.

“These groups generally have the highest rates of substance use in McHenry County as well,” Sachs and Wasson added. “The recent spike in fatal overdoses that were seen in 2020 was due to fentanyl. This is the main substance involved in fatal overdoses in 2021-2022 as well.”

A few years back, the MCDH launched its Opioid Surveillance, Prevention and Response Program to respond to the opioid crisis. It uses surveillance data and information from community partners to determine increases in overdoses and deaths, called clusters.

“In response to clusters,” Sachs and Wasson wrote, “we send out communications to the Opioid Surveillance Workgroup, professionals in this domain and the community.”

The workgroup includes community members involved in opioid prevention and response activities, such as the Substance Abuse Coalition, law enforcement, hospitals and emergency medical services. Members work to communicate information and develop responses to clusters.

“MCDH has also created an Overdose Prevention and Response Team that distributes resources, education and Naloxone in the community,” Sachs and Wasson added. “Naloxone can be obtained for free at both Health Department locations. MCDH also provides presentations … in the schools.”

Sachs and Wasson add that several Illinois laws aid the community in addressing the opioid epidemic. For example, the Hospital Licensing Act requiring hospitals to report overdose treatment within 48 hours aids in collecting data for the Opioid Surveillance Report.

The “Good Samaritan” Act also protects individuals using opioids and those helping in case of an overdose. It allows a person to call 911 or go to an emergency room without being prosecuted for possessing certain drugs.

“The state [also] has a policy that allows any organization or community member to request Narcan [Naloxone brand] from the state for free,” Sachs and Wasson added. “This allows many organizations, including MCDH, to give out Narcan to the public.”

Even when no opioid-related clusters occur, the MCDH regularly meets with the Opioid Surveillance Workgroup to evaluate changes in the opioid epidemic and discuss surveillance, prevention and response initiatives.

“There have not been any major changes in the opioid epidemic this year in comparison to previous years,” Sachs and Wasson conclude. “Based on current data, our fatal and non-fatal overdoses are on track to be lower for 2022 in comparison to previous years.”

The Substance Abuse Coalition

The Substance Abuse Coalition, a local organization, provides services for individuals struggling with substance use. It works with local government entities and nearly 300 members to combat the epidemic. Represented are schools, governments, law enforcement, parents and more.

Together, members look at substance use from different angles to determine policy and gaps in services.

“To anybody in the community, we offer help connecting to treatment providers if people have either no insurance or poor insurance,” Program Coordinator Laurie Crain said. “We can also link to recovery services like Alcoholics Anonymous and other recovery programs for specific groups.”

The Coalition also provides resources for its member organizations and educational programs for schools, especially when there are increases in overdose deaths.

“We try to keep people informed, so they know what’s happening in our community real-time,” Crain said. “That kind of activates the partners to offer support that might be needed to keep [overdose and death] numbers lower and get help outwards.”

Crain adds that SAC, first and foremost, seeks to help those struggling. Because of this, when a person uses its resources, they are not reported to law enforcement for possessing controlled substances.

“We understand that people are human and need help,” she said. “There are people who say, ‘I’m using. I don’t want to stop, but I want to understand something.’ So we have partners who will educate them on how to use smarter, so they don’t run as many risks of overdosing.”

To help, the Coalition encourages individuals to test their drugs for fentanyl, the substance most commonly responsible for overdoses in the county. Community organizations like Live4Lali and Warp Corps offer fentanyl test strips at no cost.

Naloxone, or Narcan, is an opioid overdose reversal medicine. The SAC promotes having it readily available, as it could be life-saving. It is available at no cost through community organizations.

“That’s what we want people to have in their hands,” Crain said. “I personally don’t have someone in my life who uses, but I carry Naloxone because if I’m in a setting where someone might use, I might need it just like CPR.”

Together, community partners and SAC have also developed a waste diversion program. In it, anyone can walk into a participating police department and say, “I need help,” and turn in their substances. There are no penalties and a person will get help with treatment.

“We work with DrugCourt, which is a different system where people agree to be in it and they get treatment, help with employment, housing and other things,” Crain said. “If they stay in the system long enough, they can have their records cleaned so they don’t have [a hard time].”

Amid the opioid epidemic, SAC continues to review its resources and establish new ones to meet the community’s needs.

“The Health Department is part of that,” Crain said. “The State’s Attorney is part of that. Whichever partners are key to developing those programs come together to do so.”

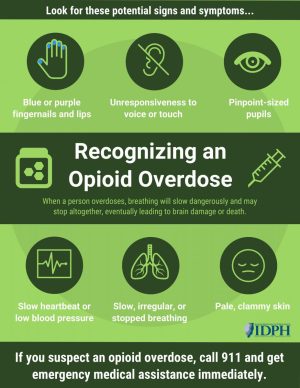

Recognizing the signs of an opioid overdose can be a matter of life or death for someone. These include unresponsiveness, slow heartbeat, pinpoint pupils, irregular or stopped breathing and pale or clammy skin. Administer Naloxone and call 911 in case of an overdose.

McHenry County has combated the epidemic for some time now; and there’s more resources available than ever.

Local organizations like the Substance Abuse Coalition, Live4Lali and Warp Corps can further provide resources, including Naloxone.

This story was originally published on The McHenry Messenger on January 18, 2023.