Clayton High School junior William Konradi began volunteering at the St. Louis County Animal Care and Control (ACC) animal shelter in the summer of 2021, at the suggestion of his mother. They chose the ACC in particular because people under the age of 18 were able to walk the dogs, as well as assist with cleaning, treat-making, laundry, and other tasks. One of the first dogs that he ever walked, Vivian, was later adopted by the Konradi Family.

“At first she was very afraid,” said Konradi, “She just sat down in the rock yard and wouldn’t leave.” Vivian eventually warmed up to Konradi and his family, finding her forever home, despite a long adoption process.

“First you had to fill out an adoption application, and they had to review it to make sure you would take care of the dog, then you had to schedule a time to meet the dog and decide if you wanted to adopt it,” said Konradi. This long process is unusual, as many other St. Louis area animal shelters allow same-day adoptions.

This lengthy adoption process is one of many complaints that volunteers, community members, and activists have had surrounding the operation and management of the ACC. It is overseen by an 11-member advisory board, which according to the St. Louis County website currently has two vacant seats and two members serving despite terms that expired in March 2022.

Two other CHS Juniors have also spent time volunteering at the ACC. Delia Zacks and Hunter Wilson spent time walking dogs, cleaning kennels, socializing cats and doing laundry.

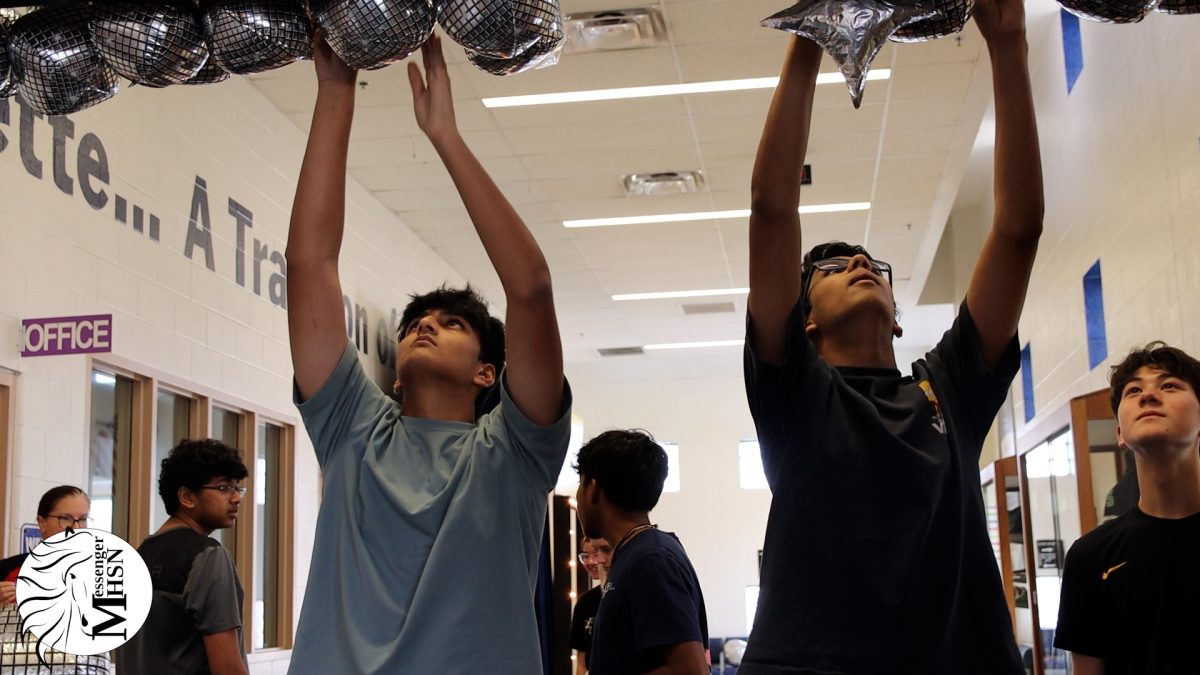

The ACC is located in a single building, a former warehouse at the intersection of Baur Boulevard and Ashby Road in Olivette. The building is landlocked with no room for expansion and very limited parking for staff, volunteers and prospective adopters.

Zacks and Wilson both described the ACC building as unsuitable for its intended purpose, with poorly maintained infrastructure that was not well maintained, leading to poor conditions for the animals living there. “There are some hallways you can’t go down. So you have to duck into these little corners and keep the dogs away from each other because they’re supposed to be 15-20 feet apart from each other at all times (to control the spread of disease). You just can’t do that,” said Zacks.

“There were automatic water dispensers in every kennel. But that didn’t work. Because they didn’t maintain them,” said Wilson.

Some volunteers felt underprepared and overworked. Volunteer training consisted of a brief tour and one, three-hour training session. “We went over the manual and then we took a dog for a walk. It wasn’t really that much. I learned from watching [more experienced volunteers] work,” said Konradi.

“There were always workers and volunteers cleaning the cages, but it was always to a state of clean enough, not clean. Whereas if there were more people, they probably could have taken the time to thoroughly clean every cage and kennel,” said Wilson.

The ACC has also suffered from understaffing and inconsistency in management, having 8 different directors between 2014 and 2018. There was also significant conflict between the County Executive, County Council and shelter leadership.

Former Acting Public Health Director Spring Schmidt came to her role in October 2018, and almost immediately, the ACC changed from a responsibility of the Office of the County Executive to one of the Public Health Department.

“(Prior to the change) The health department hadn’t really had any contact with Animal Control for five years. The ACC had not been appropriately managed,” said Schmidt.

Schmidt was tasked with hiring a variety of new leadership at the shelter, meeting with the advisory board, staff and volunteers, and educating herself on the operation of animal shelters. In addition to conducting meetings with stakeholders, she visited the shelter frequently and reviewed weekly reports.

On the recommendation of the advisory board, Schmidt authorized an audit of the facility. It revealed a slew of additional problems including overcrowding, rampant infectious disease and even a fudged euthanasia rate, which appeared to reach the low of 10 percent needed for a shelter to achieve no-kill designation.

The audit, performed by Citygate in early 2019, revealed that the shelter was requiring owners who surrendered their animals to check a box on an intake form labeled “ORE”, without revealing to the owners that this stood for owner-requested euthanasia. Owner-requested euthanasia numbers are not counted in the data that is used to determine whether shelters are no-kill. Nationally, the average percentage of animals in a shelter who are considered “ORE” is 2.5 percent. At the ACC in 2018, 14.3 percent of animals were categorized as “ORE”.

This policy of forcing owners to surrender their animals to sign euthanasia agreements began under embattled former Director Beth Vesco-Mock, who was fired by Steve Stenger. It was in place for at least a year, causing the unintended deaths of countless animals.

“It’s completely unethical,” said Schmidt, “and it’s something I didn’t know about.”

Schmidt was informed about the policy by a staffer just days before the release of the audit and immediately met with the staff to inform them of the end of the policy.

“People are not required to sign away euthanasia rights in order to surrender their animal,” said Schmidt.

In addition, euthanasia at the shelter was subject to many record-keeping mistakes. In 2018, 236 animals were categorized as ORE when coming into the shelter but 641 were categorized that way in end-of-year outcome data. When the ORE numbers are added to traditional euthanasia numbers, 25 percent of the ACC population was euthanized in 2018, much higher than the six and seven percent respectively at the City of St. Louis and St. Charles County government animal shelters.

In response to the audit, Schmidt also worked to increase transparency in data reporting and to improve the live release rate of the shelter, though she lacked the funding to implement some recommendations such as removing small kennels and replacing them with larger ones, and obtaining clearer outdoor signage.

Another major issue from the report and a concern of Schmidt’s was the excessive length of stay for animals in the shelter. The average length of stay for dogs was 20 days, and this statistic was doubled for dogs who were eventually adopted dogs.

“The phrase that stuck with me from the audit was ‘animals were not moved with urgency or purpose,’” said Schmidt.

The audit also noted that not enough animals were transferred to rescue groups and that animals were not well-marketed for adoption.

A long stay in a shelter can have serious consequences for a dog, including behavioral and health issues brought upon by stress and an increased risk of infectious disease. Infectious disease risks were compounded at the ACC by poor cleaning protocols including improperly diluted cleaning solutions and insufficient time for staff to clean kennels.

Understaffing also contributed to insufficient cleaning. “Lisa (Langeneckert, ACC Volunteer Coordinator) made it pretty clear that they were understaffed and any help they could get was appreciated,” said Wilson.

In response to the audit, Schmidt decided to write an (RFP) or request for proposals, seeking plans from non-profit organizations that could manage shelter operations. In October 2019, the St. Louis County Council authorized the Department of Public Health to release the RFP. This raised concerns among many staff members that they would be fired and concerns among advocates about corruption. Schmidt claimed that no pieces of the RFP were given to non-profits prior to the official publication.

Despite all of this, the RFP was not published until two years later, in the fall of 2021, with only a week for organizations to submit bids, with very specific and stringent minimum requirements to meet. Typically, potential candidates are given at least a month to submit proposals. In addition, the public written question period on this RFP was originally only one day but was later amended to add seven additional days, limiting public input.

Schmidt attributed the delay on the RFP to Covid.

“We had written part of the RFP when we began ramping up Covid operations in January 2020. We had part of the proposal done when we had our first case and Covid just threw all of that off,” said Schmidt.

Only two organizations submitted proposals to the County, the APA (Animal Protection Association of Missouri) and CARE STL (Center for Animal Rescue and Enrichment of St. Louis). The proposals were reviewed by six evaluators, whose names were not released by the County but were described as County employees and subject matter experts. Schmidt was a part of the evaluation committee. The APA had an extremely detailed proposal including resumes of staff, descriptions of current procedures and plans for transition, and internal audits of years 2017-2021.

The APA’s contract for five years and 15.8 million dollars was approved by the County Council and signed in May 2022, stating “There is a dedicated team of staff and volunteers currently caring for the animals. However, the facility is understaffed, overcrowded, and they do not have the capacity to provide proper animal husbandry.”

Even with the APA takeover looming, former staff and community members have made the ACC and the St. Louis County Department of Public Health the subject of several lawsuits since the audit.

Former shelter population manager Amanda Zatorski sued the County for wrongful termination after she was fired in December 2020. She cited conflicts with Schmidt and former ACC executive director Vannessa Duris and violations of whistleblower protections for speaking out against plans to find a non-profit partner. Zatorski also claimed that certain non-profits were given undue influence in the process of writing the RFP.

St. Louis County resident Erin Bulfin sued the County in 2020 for wrongfully euthanizing their dog Daisy, under the deceptive ORE authorization box, while she was in bite quarantine at the ACC.

In addition, lawyer Mark Pedroli is suing on behalf of Karen Runk and Amanda Zatorski, over the Public Health Department’s destruction of 20,000 pounds of documents infested with mice and cockroaches in the fall of 2022, just prior to the APA takeover. Many of these documents are relevant to their ongoing lawsuits and their destruction is in violation of Missouri’s Open Records law, the Sunshine Act.

In the fall of 2022, the County prepared intensively for the APA, including pest control spraying of the majority of the facility, and increased cleaning and laundry. The shelter also euthanized 17 aggressive dogs between September and November, County spokesperson Christopher Ave told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Part of the APA’s contract included a discovery period in Fall of 2022, to prepare for the transition. During its observations, the APA noted a lack of PPE usage by staff, a lack of preventative medicine for dogs, and inadequate bathing all contributing to the spread of infectious disease, leading to an outbreak of parvovirus in early fall 2022. The APA also noted that the shelter animals did not receive adequate exercise or soft places to lie down in their kennels. Many of these issues had been noted previously in the 2019 audit.

The organization took over shelter operations on December 5, 2022, with an amended contract that included many operational and structural changes with a 2.7 million dollar annual operating budget.

Key operational changes include more stringent cleaning procedures and the creation of a foster program. “We created a foster program at APA Olivette (new name for ACC). And intake, adoptions, animal care, and veterinary medicine are within the scope of this partnership (with the County) and will be under the purview of the APA,” said APA spokesperson KT Stuckenschneider.

Animal control operations as well as building ownership and maintenance remain under the County Department of Public Health purview. Despite this division of responsibility, the APA is planning sweeping changes.

“There will be changes to the physical structure (of the ACC building),” said Stuckenschneider.

According to the APA’s December 2022 amended contract, these changes include kennel door replacements, costing 6,000 dollars, outdoor awning replacements for 32,000 dollars, 128,000 dollars for a new animal intake space and 132,000 dollars for a new volunteer coordinator office.

Some community members still have concerns about a non-profit’s ability to run a government shelter. Government animal shelters, including the ACC, are primarily responsible for enforcing County ordinances including quarantining dogs for bites, caring for neglected and aggressive animals and also deal with a larger variety of animals. Private animal shelters might be used to dealing with cats and dogs, which account for the large majority of animals, but would rarely see other animals such as pigs, cows, or snakes.

“There was a court case where there were tarantulas that were impounded that had babies and we had to count. We had to collect a cow from someone’s backyard,” said Schmidt.

Schmidt emphasized that all farm animals are cared for appropriately and this particular cow was impounded in conjunction with a farm shelter.

Shelters like the ACC have a duty to care for all animals and enforce rules and regulations regarding them in their area.

One commonality between non-profit and government animal shelters is the necessity of volunteers. Volunteers were a large part of the working base of the ACC and some have been alienated by the change in management, which came with new duties and age restrictions. But the APA is still in need of volunteers.

“The existing volunteer base at APA Olivette is truly incredible. None of this could be done without them,” said Stuckenschneider.

Others were concerned about ACC employees losing their jobs under new management. St. Louis County said it was committed to reassigning all employees not hired by the APA.

“ACC employees had the opportunity to apply to the APA for open positions, and if qualified, they were selected for the positions,” said Stuckenschneider.

In addition, the APA is attempting to change several county ordinances to increase or create fees for services that the county previously provided free or at lower costs. These include fees for adoptions, ORE and cremation, microchipping and rabies vaccinations. The County Council must approve these changes.

CHS students have mostly positive opinions on the changes, despite the fact that the change means people under the age of 18 are no longer allowed to walk dogs, the most common and urgent volunteer task.

“All the dogs are pretty good, but it was clear (under previous management) they did not get the attention that they needed,” said Wilson.

“It’s going to be better for the animals because there’s going to be more staff,” said Konradi.

“Change needs to be made because of how much pressure was put on the volunteers to make up for the fact that the County wasn’t providing enough funding,” said Zacks.

The APA contract will run for five years, with three, one-year extensions possible. Volunteers, advocates, staff and community members wait to see if animal care will improve under the new management.

Schmidt, who left the Public Health Department in September 2022, wants the best for the animals and the new management.

“The animals deserve for the shelter to be well managed,” said Schmidt.

This story was originally published on The Globe on January 24, 2023.