Loss of longevity in television threatens longform storytelling

Noor Fatima

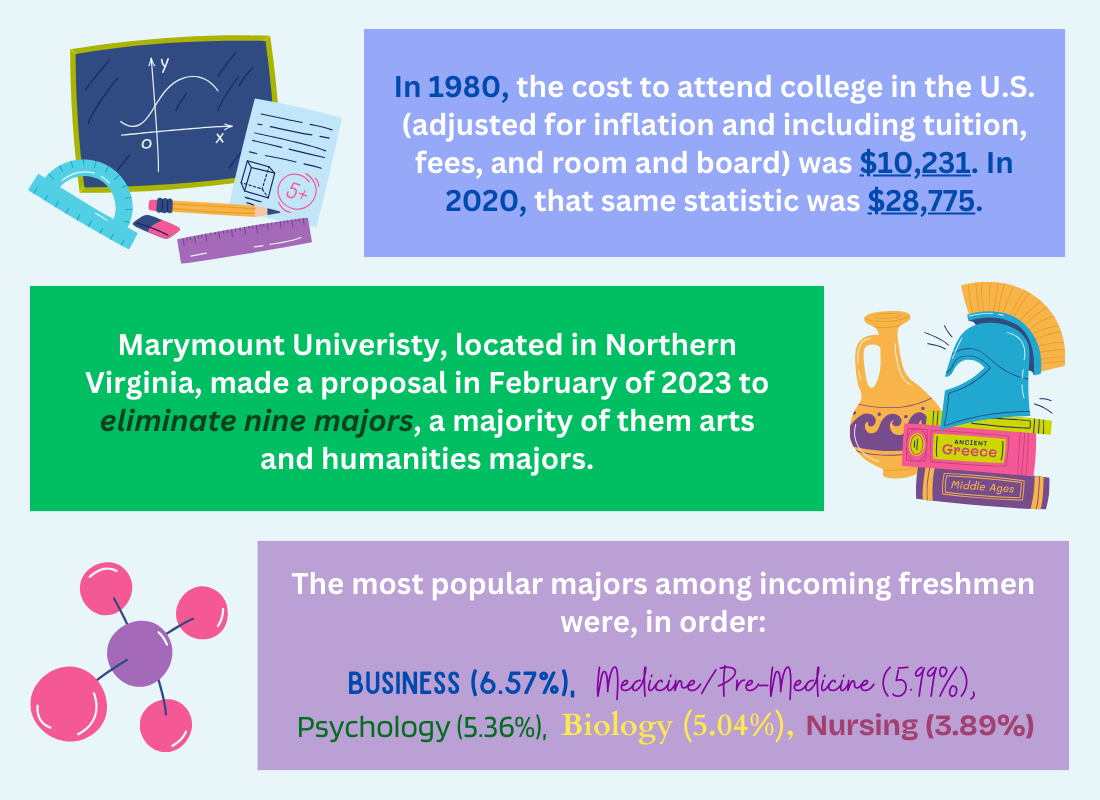

As streaming has become more popular, competition in the industry has exponentially increased, many streaming platforms have turned to canceling shows that are not profitable after the first or second seasons in order to maximize profits. The Sidekick entertainment editor Saniya Koppikar thinks as long as the appreciation of art and storytelling is forgotten in favor of profits, the cancellation storm will rumble on.

March 9, 2023

In the entertainment industry, attention is historically fickle.

Actors grow old and gradually fade from the public eye, or say something deemed “cancellable” and are intentionally erased. Trends come and go. Franchises fizzle out. Reprises of characters bring the franchises roaring back.

Its problems have been picked apart through the decades, but as the industry enters a new age with streaming, it is perhaps more mercurial than ever––especially in regards to television.

The unfortunate mark of modern television is that audience response is the end-all-be-all. Netflix bases the livelihood of their content on user metrics, HBO stops production in the name of producing “the exact right things rather than simply pushing out as much content as possible.”

Show after show is canceled.

As streaming services roll out monthly previews of new shows, it is hard not to wonder how many of them will live to see a second season. Unfortunately, viewers are not the only ones wondering; the people in production are as well.

And so came along the limited series.

The model works especially well on streaming services rather than being on traditional broadcast television, as streaming services do not need numbers at specific times like traditional networks do. Limited series are also rewatchable, which is integral for streaming service content, even though they do not repeatedly draw back viewers for new content.

Untethered to the needs of a traditional long-running series, a limited series allows for an ultimate win/win, where a hit show can be extended and a flop is easily forgotten.

Even with series of typical length, seasons have begun to shrink. The 26-episode season is rare, replaced with less episodes of a longer length even with largely successful series, like Netflix’s “Stranger Things” and “Wednesday,” where producers are able to plan ahead.

“It’s always looking at the future, and when we sit down to create a show, it’s looking at multiple seasons, ideally,” said “Wednesday” showrunner Miles Millar in an interview with Variety. “That’s never expected, but that’s the anticipation that hopefully the show is successful. So you always lay out at least three or four seasons’ worth of potential storylines for the characters.”

Shortly after “Wednesday’s” debut, Netflix announced that the series set a new platform record for most hours viewed for an English language series in its first week with more than 341 million hours. The series grew to the second biggest English language season of television on Netflix with more than 1.2 billion hours viewed within its first 28 days.

Needless to say, “Wednesday” was renewed for a second season. The metrics divined it. But with other series, like Netflix’s “The Society,” producers are cut off at the knees.

“Anyone who’s on Netflix knows the chances of five seasons are diminishing, unless you have ratings of a certain type,” said “The Society” creator Christopher Keyser after the show’s cancellation. “And we certainly didn’t have ‘Stranger Things’ ratings, so I was not expecting that we would exist for that long.”

Still, Keyser said, he had planned for the series to be “longer than one season for certain,” and therefore developed a plan for the overarching story––a story that will likely not be shared with “The Society’s” disappointed audience due to Netflix still owning and producing the show.

After “The Society’s” cancellation, #savethesociety trended worldwide. But the decision held.

It is true, the beauty of television lies in the anticipation.

With the rise of streaming, though, the definition of anticipation changed: rather than waiting on an episode-by-episode basis, most shows dropped entire seasons at once. Binge-watching rose. The time between seasons was empty and cavernous.

Eventually, the industry doubled back. Many shows went back to releasing episodes on a weekly-basis in order to drum up enthusiasm. But the central theme has always been anticipation. The nature of television demands it: movies are one-and-done deals to gauge an audience’s reaction, while television is constantly throwing concepts at the wall and seeing what sticks, overarching stories and building up characterization.

Knowing that the stories and characterization might be cut short has unequivocally changed the industry of television, and the increased length of episodes and rise of the limited-series model are just a few examples of how.

Though truncated content often aims to put quality above quantity, oftentimes, both end up suffering anyway. It is almost as if, though the producers themselves are the ones making the pacing changes, they do not know how to adapt to them.

Of course, the blame cannot all fall upon the production side. Streaming has created a surge in competition, and in turn a constant need for new content from viewers. Most shows are forgotten within weeks of their initial buzz, and the ones that are not quickly become old from the constant attention.

It is an impossible situation. How are viewers supposed to savor media when there is constantly new content to keep up with? How are producers supposed to keep beloved shows afloat when they are trying to fulfill the demand for new content?

What first was a win/win situation is now lose/lose, because the original mission has been lost: appreciating art and storytelling. So while profits are important, they cannot be everything.

Treating them so puts television into a deadlock.

This story was originally published on Coppell Student Media on March 7, 2023.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)