Recent Ukraine and COVID-19 supply chain shocks are yet another reminder of the world’s worsening food security crisis. They have brought hunger to millions of people, especially in low-income countries with defunct agricultural production.

The global food system has been broken for decades. Purchasing or wasting less food won’t directly feed starving children in other countries, but there are some truths to the platitude; an overabundance of rashly grown food in high-income countries actually does plunder from the world’s poorest people.

A 2019 report by The Food and Land Use Coalition calculated we spend $1 million every minute on global farm subsidies, yet food prices remain high, billions of people are either underfed or overweight, and a third of all our food is wasted.

Over the second half of the twentieth century, through the influence of the Farm Bill — a key component of former President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal — the direction of trade started to flow toward developing countries. The Bill’s export subsidies created new markets for U.S. agricultural goods and substantially increased the amount of food imports globally, most dramatically global imports of wheat from the U.S. and other developed nations that followed suit.

In short, rich-country farm subsidies incentivize farmers to focus on producing crops that receive the most subsidies already, which often leads to overproduction of these crops that are then exported to developing countries. When these subsidized, underpriced crops are dumped into developing markets, it’s difficult for local farmers who receive fewer subsidies (or none) to compete, contributing to the long-term global trend of rural depopulation.

The Fairtrade Foundation stated $47 billion in subsidies paid to rich-country producers created price barriers for 15 million cotton farmers across West Africa, forcing 5 million of the world’s poorest farming families out of business and into deeper poverty; many West Africans were forced to abandon systems that had worked in their cultures for centuries. The subsidies are part of why researchers concluded agricultural production in sub-Saharan Africa in recent years remains low compared to the rest of the world.

Carnegie Endowment revealed how under NAFTA, subsidized imports of low-priced rice, beef, poultry and pork from the U.S. threw at least 1.3 million Mexican farmers out of work; many of those farmers were then forced to migrate to the U.S.

Global dependency at the expense of local production is especially devastating during price shocks. In Africa, because an emphasis on free trade undercut local food production for a quarter of a decade, a report found West Africa’s increased reliance on imported rice left millions of Africans hungry when global rice prices doubled in 2008.

“Trade flows, as well as food reserves, are key factors affecting a country’s exposure to production shocks; also, high reliance on imports can accentuate the risk of critical food supply losses,” many scholars wrote on Frontiers.

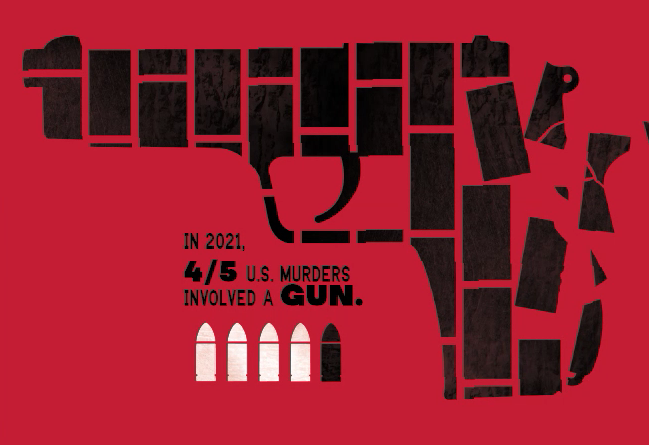

More recently, supply chain disruptions due to COVID-19 drastically raised food prices across the globe, increasing the severity of food insecurity for the 821 million people around the world who go to bed hungry every night. Furthermore, the war in Ukraine has disrupted almost a third of the world’s wheat market, worsening the food security crisis already exacerbated by COVID-19.

Farm subsidies’ desired effect for the subsidized country is lowering food prices by maximizing crop yields and making farming easier by providing financial risk mitigation for weather, new technology or disruptions in demand. But CATO found they instead induce excess production, less efficient planting, overuse of marginal farmland, excess borrowing and insufficient attention to cost control.

“Because farmers aim to maximize their profit and government support is a major source of their income, many farmers follow the money and convert biodiverse tropical forests — which store huge amounts of carbon — into sprawling single-crop farms,” the World Resources Institute wrote.

Almost all farm subsidies incentivize farmers to clear forests to plant subsidized cash crops; just 1% are used to benefit the environment. Such practices contribute to land degradation and desertification, which in turn reduces the amount of arable land available for future farming.

Instead of lowering food prices, the FOLU report found the cost of the subsidies is greater than price reductions from mass production, ensuring food remains costly. In fact, growing healthy, sustainable food could actually cut U.S. food prices because the condition of farmland would improve and make growing food easier.

“We should be subsidizing a system in which you’ve got a farm that uses crop rotation and pest management, like having natural biological controls for their pests and using a type of crop like cover crop that will regenerate the soil without fertilizers,” DVHS AP Environmental Science teacher Heida Shaw said.

Restoring land and sustainable farming may have high initial financial costs, but repurposing farm subsidies to these objectives could still provide $40 billion per year in extra smallholder income, additional food for close to 200 million more people and 2 gigatons per year in sequestered carbon dioxide.

To change the global food system, there needs to be a shift towards more sustainable farming practices and a reduction in subsidies for unsustainable practices. This would not only improve the condition of farmland but also ensure that farmers can earn a fair income without being reliant on subsidies to remain competitive. Ultimately, a sustainable food system would benefit everyone, from farmers to consumers to the environment, and it’s time that step is taken.

This story was originally published on Wildcat Tribune on March 30, 2023.