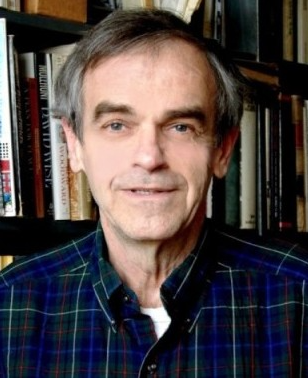

John Tinker is best known as a participant in the 1969 Supreme Court case, Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District. The case determined that students do not lose their right to free speech once they enter a school building. From that point forward, Tinker’s family became known civil rights activists, although they had advocated for peace and justice for many years before the case that bears their name. Some of John Tinker’s first encounters with the civil rights movement occurred in Atlantic, Iowa, where he lived from 1953 to 1957.

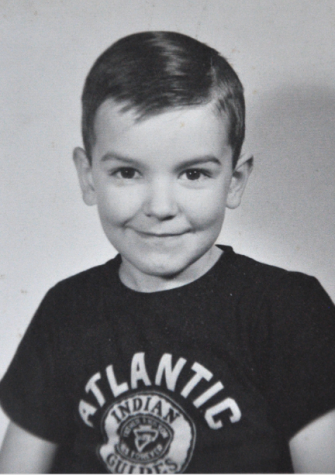

John Tinker was about five years old when he attended first grade at the now-closed Jackson Elementary School on Cedar Street. He doesn’t remember who his teacher was, but she had an impact on him that would last a lifetime. “I remember one day her walking down the aisle and having us all show her our hands,” Tinker said. When the teacher got to the Black girl in the class, she showed the children the girl’s hand and said, “Look how dirty this hand is.” That was the first time Tinker was aware of a civil rights issue in America. “I think she may have been showing us just how dirty the black kids were.” He described the teacher’s action as “a pretty ugly thing to [do].”

Tinker remembers another incident in which Black children were called dirty, but he is unsure on if the two events are related. When he lived in Atlantic, the popular Sunnyside Pool was segregated by race. “The issue they said [was] the black kids were too dirty to swim in the pool,” Tinker said. Tinker’s father was the pastor of the Methodist Church in Atlantic, and his mother was the advisor of the Methodist Youth Fellowship. The information regarding the segregated swimming pool came to be known in the Church, so Tinker’s father took the issue to the town council. “There was a nineteenth-century public accommodations law in Iowa, so they really had to let the Black kids use the swimming pool,” he said, but the council didn’t react positively to the issue being brought up to them. “The Board at the church, at the time, didn’t renew my dad’s contract.”

One day, when Tinker was still five years old, his father picked him up from Jackson Elementary and said to him, “You know, there are some things that we talk about in the family that we don’t really want to talk about in the neighborhood.” Tinker reflected, “He was trying to warn me to keep family business in the family.” Although he doesn’t remember for sure, he thinks someone had said a “bad word” when talking to his dad about the racial situation. “He was quite upset. He took me on a walk and he said, ‘John, I want you to know that I’m never going to kill anybody.’ I couldn’t understand why he was telling me that,” Tinker said. As it turns out, “He was just sharing with me a life commitment that he had to pacifism.”

Tinker doesn’t know how many of the people were on each side of the issue, but he remembered there were “a lot of people in Atlantic that did support racial integration.” He said, “Whenever I tell this story I feel bad because I don’t mean to be putting anything on Atlantic. I loved Atlantic.”

After his father lost employment in Atlantic, the Tinker family moved to Des Moines, where Tinker’s mom “became involved in local civil rights activities.” She had Black friends whose children got to know Tinker and his siblings. “We invited them to come to church with us in Des Moines, and that church also really didn’t want to have Black people in their church,” he said. “They didn’t want to have the preacher engaged in a civil rights movement, which my dad was.” Tinker said his dad “lost that job too,” which plays into an even bigger story.

The Quakers offered Tinker’s dad a position after he lost his job in Des Moines. They were looking for someone who was passionate about civil rights. He became the Peace Education Secretary for the American Friends Service Committee, which is “a major Quaker organization that provides relief” among other things. His father’s job was to have lectures, present programs, and even “bring in experts to tell us about world affairs.” Tinker said that when his father held summer camps, “Families would come from around the country and listen to world affairs lectures during the week and have discussions about what’s going on in the world.”

The Tinkers found peace with the Quakers, who are historically pacifists and leaders in the anti-slavery movement. “By 1965, the war in Vietnam had started to heat up,” Tinker said. “There was a call for a national peace demonstration in Washington, [D.C.] and my dad helped coordinate a couple of busloads of people to go from Iowa,” most of which were students. Tinker was allowed to go on that trip with his mother, and he said it was an “amazing experience” because people agreed with his family’s viewpoint for once. “Having been used to being a real small minority, and then suddenly you’re surrounded by people that agree with you. It can really boost your confidence and your opinion,” Tinker said.

On the bus ride back from Washington, D.C., many people discussed how to continue raising awareness about the Vietnam War. Tinker said, “A man had heard of wearing black armbands to protest the war, to mourn the deaths on both sides. That sounded like a good idea so everybody on the bus decided that’s what we would promote.” Tinker attended both the Quaker and Unitarian youth groups at the time, and he, along with three other high school students and fellow members of the Unitarian youth group, decided to wear the armbands. “I was really wearing the black armband as part of that high-school group,” Tinker said.

Another participant in the protest named Ross Peterson wrote an article about it for his school newspaper. Tinker said, “The faculty advisor to the newspaper saw the article and apparently was concerned and contacted the principal of that school. The principal of that school contacted the principals of the other schools.” They met up and decided to forbid the wearing of black armbands in the schools and then contacted the local newspaper. “We found out about it by reading the newspaper,” Tinker said. “We were kind of in shock.”

The next morning while Tinker was delivering newspapers before school, he found himself thinking “We really need to have a meeting to talk among ourselves of how we’re going to respond to this.” He tried to contact his sister Mary Beth, who also participated in the protest, but she decided to go to school early that day. Instead, he got on the phone with another participant in the protest, Chris Eckhardt, who said, “I don’t care, I’m going to wear it anyway.” Other participants, including Ross Peterson and Bruce Clark, decided to hold off.

That day, Mary Beth and Chris got kicked out of school. “We had a meeting at Chris’s house and we tried to call the school board president to explain we were not planning to make a disruption,” Tinker said. “He didn’t want to talk to us about it.” Tinker and the group decided to “go ahead and wear them anyway.” Tinker said, “We thought we had a First Amendment right to express our opinion.” Originally, there were about 12 to 15 kids involved in the protest, but by that time, there were only about five or six students altogether. They wanted to continue wearing the armbands and “didn’t mind being kicked out of school.”

As one might expect, they did get kicked out. Afterward, they had a meeting with the Iowa Civil Liberties lawyer who thought they had a First Amendment case. “He recommended that we go back to school without armbands on so that we wouldn’t be truant, and so that wouldn’t make the issue more complex,” Tinker said. The group decided to call off the armbands while the lawyer worked behind the scenes.

Eventually, the group was able to sue at the federal court, where they lost. They then appealed to the appelate court before losing there too. Tinker said, “The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case because there was a conflicting case coming out of the Fifth Circuit called Burnside v. Byars.” Similarly, that case dealt with students that had worn “One man, one vote” civil rights buttons, another situation involving symbolic speech. They sued, but unlike Tinker’s story, the Fifth Circuit Court agreed with the students. “The Supreme Court, probably in order to clarify the conflict between the two circuit courts, agreed to hear the case,” Tinker said.

Tinker wants to point out that he was not the leader of the movement in his group. “I was supported by a peace movement. I was not really a leader of that little group of armband wearers. It really was Bruce Clark and Ross Peterson, but neither of them wanted to participate in the armband case,” he said. When Tinker talked to Bruce later about the incident, he admitted that he didn’t want to distract from the issue of the Vietnam War by making a First Amendment case, which “surprised” Tinker, who was the first to testify. He said, “It was surely quite an experience to be in the Court. I was surrounded by friends, the people in the courtroom mostly were our supporters I think.” He said that he was not nervous when telling his recollection of the story.

On Feb. 24, 1969, Supreme Court ruled in favor of Tinker. They said Des Moines Independent Community School District’s prohibition of black armbands violated the student’s freedom of speech and protection of symbolic speech. In the majority opinion, Justice Abe Fortas wrote that students do not lose that right when they step onto school property unless it were to “materially and substantially interfere” with the learning process in the school, which the group of armband wearers was not doing.

When the decision came out, Tinker had a sense of “the system works,” but later, “I had to let that one go because so often the system does not work.” He said, “It was a real high point in my life to realize that we had taken a stand that actually had affected the reality for a lot of people.” The case made history for students’ rights.

After the case, Tinker worked a number of jobs in many different cities across Iowa, collecting varied experiences along the way. He even got to know the man who had invented the trampoline. Eventually, he got into computer programming after being “a jack of all trades,” and he ended up “writing computer code for a multi-billion dollar billings system for the Telecommunications Company.” Currently, he is retired and running a local radio station in Fayette, Missouri.

Tinker said he has “nothing but affection for Atlantic” after all these years. “I’d like to come to Atlantic and present.” He wants residents to know that he doesn’t “want to accuse the town of Atlantic of being racist. I don’t want to put anybody in Atlantic on the defensive for [that] part of the story.” Tinker still has friends in the area that he remembers fondly. “I remember going to Sunnyside Park and I remember really wonderful people. We played, ran around the neighborhood, and it was a beautiful time in my life.”

Tinker’s legacy affects the students of Atlantic, as well as all of the students across the United States. His hope is that students will continue to get involved in affairs of the world and fight for change when they deem it necessary. “Encourage the kids to try to figure out what’s going on in the world. I think we’re in trouble if we don’t,” Tinker said.

This story was originally published on AHSneedle on April 25, 2023.