Irvin Horn takes an hour to put on his makeup, and he’s not even close to being done with getting dressed. He still has to do his hair and get into costume. In a couple hours he’ll step on stage at a club, the lights going down and a song coming on, and transform into the classy and powerful Chanel, his drag persona.

Horn’s Chanel wears colorful long nails, long eyelashes and hair, and glittery earrings. But his drag persona is the polar opposite of how he was raised.

Horn is from Corsicana, a quaint town in northeast Texas with a population of 25,000 people. As a child, Horn was raised in the church, with his grandmother working as a missionary and his uncle as a pastor.

“I grew up in a small country town so [drag] wasn’t something you saw on TV or in a TV show. It wasn’t something that I was exposed to. Probably about [age] 14 or so is the first time I actually saw [a drag queen] in person. I was like, ‘I want to do that.’”

Now, Horn is 26 and is still a relatively new performer, only having participated in drag for a year. Horn travels to different venues and performs once or twice a month. His drag name, Chanel, was easy for him to come up with.

“I knew I wanted something that was classy but easy [to remember] too,” Horn said. “So Chanel it was.”

Cody York is also from Corsicana, Texas, and although he is from the same small town as Horn, the two had vastly different childhoods. While Horn grew up in a religious family where he rarely saw queerness, York grew up in a very close and accepting family. He came out as gay when he was 12 and knew he wanted to do drag at 17. But when York was first starting out in 2011, being a drag performer was dangerous due to threats of violence for being not only openly queer but an open drag performer in a small town.

“Being in a small town and being a drag queen, when I would get ready to drive to perform I couldn’t stop at a convenience store to get gas,” York said. “You [couldn’t] make any stops; you had to drive straight to where you were going. It wasn’t okay for you to look like that and be in public in small towns that I was performing in.”

At 32, York has been a drag performer for 13 years. His drag name is Koti. With his drag mother’s help, he picked it because it was close to his real name. While he admits that things have definitely gotten better since he started years ago, he still has to deal with misconceptions about drag performers.

“Everyone thinks that we’re child predators,” York said. “People think that we perform at brunch or for children because we are predators when that has nothing to do with any of it.”

Even without all of the outside scrutiny that can come with being a drag queen, drag is not an easy job. Being a drag performer is intensive. Even preparation for a performance sometimes takes planning up to a week in advance. Performers have to make sure that they not only have the right outfits, but also that the outfits fit correctly. Preparations can also vary for each performer, and each venue or club they are at.

“Song is a big part of it,” Horn said. “You want to be performing the right songs for the right audience so knowing where you’re at plays a part in [performing]. After that, the day of the performance, makeup is my first go-to, so I start with my makeup. That can take about an hour and sometimes two, then [I] go right into the hair. Following that [I get] dressed. [You have to] make sure you don’t have wardrobe malfunction, [and] try to prep for those things.”

All of these tedious preparations and skills that are crucial to being a successful drag performer are often taught to drag performers by their mentors, which are called drag mothers.

“There’s a drag family which [includes] a drag mother and drag grandparents,” Horn said. “So [you’re] learning all the tips and tricks of being a performer.”

Drag mothers are more experienced and acclaimed drag queens in the drag community who have been performing for longer. Drag mothers will mentor new drag queens – their “daughters” – as they learn performing skills and develop their on-stage personas, as well as technical skills such as how to do their makeup, how to pick songs, how to wear their costumes, and how to pick their drag names.

Kelly Kline is a drag mother and grandmother who started performing in 1987 and has been performing for 36 years. Kline has 50 drag kids, some of whom have gone on to have their own drag kids.

Kline grew up in Brownsville, Texas, a southern Texas border town where Texas meets the Gulf of Mexico. Kline always knew she was different growing up, and always felt more feminine than others. It all finally made sense for Kline in highschool when she was playing bingo at a friend’s house when Kline’s friend suggested Kline put on dresses and makeup as a dare.

“One of my friends who was part of that group, his boyfriend’s family owned the only gay club in Brownsville, Texas,” Kline said. “So they dared me to do drag and two weeks later, I showed up to do amateur drag and I won.”

That contest Kline won was the club’s calendar contest for Miss February. She then went on to win for the year, and later she won Miss Rio Grande Valley.

Kline was ecstatic on stage and it felt like she was on top of the world. But she soon hit a low when she came out to her family as transgender. Kline grew up in a close knit family that was open-minded and friendly to the LGBTQA+ community, but that changed when she came out. Her family stopped talking to her and it devastated her. She fell into a severe depression and, shortly after graduating high school, moved in with her best friend and their aunt in Austin.

When Kline moved in, her friend’s aunt called Kline’s family, wondering why Kline had moved to Austin. Kline’s family outed her and her friend’s aunt kicked her out within hours of moving in.

“At that moment, I was lost,” Kline said. “[I had] never been to the city before. But from where I was I heard music and I walked towards the music and lo and behold, it was a gay club here in Austin. Unfortunately, I was a minor and they let me into the club and I was drinking when I shouldn’t have been, but at that point in my life, I didn’t care. I basically wanted to die because my family didn’t want anything to do with me.”

While Kline was able to make friends in the club she was visiting, she was still deep in the depression that resulted from being disowned by her family, and living in a time that was still deeply intolerant toward the LGBTQA+ community. Kline attempted suicide but fortunately was unsuccessful.

“A nosy neighbor saw me in the pool and called 911 and I woke up in the hospital. And as I was waking up, they were playing the Wonder Woman TV series. And I’ve always been a Wonder Woman fan but the Wonder Woman TV series was on an episode where Wonder Woman’s mom tells Wonder Woman, ‘You are a Wonder Woman,’ and for some reason that really touched me. So when I heard that I discovered that I felt that I was here for a reason.”

From that day on, Kline decided that she had a purpose: to help and advocate for the LGBTQA+ community. Kline became involved in political advocacy, as well as fundraising for nonprofits — 22, to be exact. She helped open clinics for the LGBTQA+ community and was a part of local government, on a LGBTQA+ commission, and also did work providing information about sexual health such as AIDS, contraception, and STI testing.

When Kline finally started performing again, the homophobia-riddled society she lived in wasn’t her only struggle. She also faced struggles inside the drag community as a Latina.

“When I moved to Austin, the queens that were here before me would always make fun of me for performing to Spanish music,” Kline said. “They said that the people here wouldn’t like Latina music or Latina entertainers, but I performed to Selena and lo and behold, I became a star overnight. That was one of the biggest challenges but I said, ‘Screw it, I’m gonna be myself.’ And so it worked out for the best.”

Kline never had a drag mother. She had to learn everything on her own. While Kline wished she had a drag mother one to help her along, she uses that desire to give her drag kids what she never had.

“I don’t only help people in drag,” Kline said, “[I] also help them finish school, graduate from college, [and] find careers. [I help with] everyday life. It’s more than just ‘drag’ for me. It’s about succeeding in life.”

Kline wants to make it clear that while being a drag queen is an extremely important part of her identity, it is not all she does. She is also a certified makeup professional and a business manager for Christian Dior cosmetics, where she is responsible for tasks such as ordering products, setting goals, producing events, all while also being responsible for the employees under her.

“People assume that sometimes [drag queens] don’t have regular everyday jobs,” Kline said. “[They assume that drag is] all we do for a living. That’s not true. You know, I have a friend who’s a doctor, I have a friend who’s an attorney, [a] friend who’s a nurse. We do [drag] because we love to show our talent and share our art with others.”

Influenced by the Wonder Woman episode that turned her life around, Kline now calls herself “The Wonder Woman of Drag,” and had a Wonder Woman costume made for her. She has occasionally shown up to the Texas Capitol dressed in her Wonder Woman costume to advocate for marriage equality protest bills like SB 12.

“When I’m on stage, I’m two things: I’m a superhero, but I’m also a leader,” Kline said. “I host events so I’m on the microphone all the time. I use my microphone to host the show and have fun, but I also use it as an opportunity to educate and inspire other generations to get involved. I remind them that even though their family might not accept them right now, they could potentially accept them later, so don’t give up.”

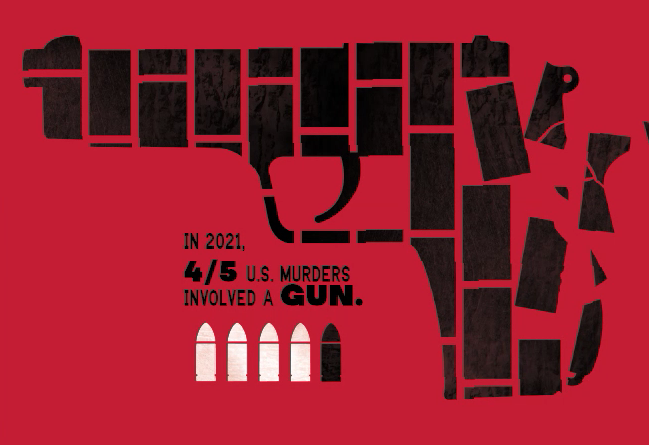

While society’s acceptance of drag queens and the LGBTQA+ community as a whole has gotten better, there are still some very prominent challenges, one of the biggest being legislation targeting these groups. Since the start of 2023, anti-LGBTQA+ legislation has swept across the country, with CNN reporting that the number of anti-LGBTQA+ legislation introduced had doubled since last year.

“[Lawmakers] were trying to pass a lot of new things that would take my form of drag completely out of the game,” York said. “So it literally takes [me] from being who I am to me being someone completely different.”

When asked what challenges they face today as drag queens, York, Horn, and Kline all mentioned Senate Bill 12 (SB 12), a bill passed in the Texas legislature in August. The bill was originally intended to classify drag shows as sexual performances, but was edited down during the legislative session and the approved version criminalizes performers who put on “sexually explicit” performances for children as well as the business who host those performers. If signed into law, violators of this bill could face up to a year in prison, and businesses hosting the performances could be fined up to $10,000.

SB 12 caused protests to erupt across the LGBTQA+ community, with critics stating that the bill’s broad language could be weaponized as a tool for discrimination against drag performers. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a lawsuit, claiming that the bill is a violation of individuals’ freedom of expression, and in late August a federal judge ruled SB 12 unconstitutional and issued an injunction, blocking it from going into effect, although the legal battle around SB 12 is still ongoing.

And Texas isn’t the only state that has introduced legislation that targets drag. According to an article from Time, anti-drag legislation has been introduced in at least 14 states.

“We battle people every day,” York said. “We battle people who don’t understand. We battle people who let their religion be the reason that they have an issue with drag when in reality, I don’t feel like religion or anything should even come into play. If you just don’t care for someone because of who they are then just say that’s what it is. The biggest challenge for us now is people not understanding or people thinking that we’re here to brainwash or have an ulterior motive.”

The first time Kline ever went to a club, men were being arrested for dancing with other men. Kline has come a long way from lying in a hospital bed, with nowhere to go and nothing to live for. She’s traveled all over Texas performing drag and seen all the ways progress has been made for the queer community, and all the work that is still left to do for equality.

“People still need love,” Kline said. “And [they] need to be reminded that it’s okay to be themselves and also need to be empowered to get involved to make a difference for a better future.”

As an accomplished career woman and an even more impressive performer, when Kline thinks of her younger self, a lost teenager who just wanted a place where she belonged, she tears up. If she could, she would tell that teenager to have hope.

“Don’t believe what they say about you,” Kline said, her voice breaking. “Don’t let the things that they do or say to you make you see the world in a different way. These are just kids who don’t know what they’re talking about. I would say focus on having hope and focus on meeting different people who accept you for who you are. And if someone has an issue or a problem with you, you have the absolute right to walk away from those people.”

Drag queens put themselves through so much — chaotic schedules, intensive preparations, scrutiny, hatred, and even violence. But through everything, they continue to put themselves at risk for what they love: performing, art, and bringing joy to others. No matter what, Texas drag queens and drag queens everywhere will continue to fight for equality and against those who let their ignorance bring harm to others – one winged eyeliner and glittery costume at a time.

This story was originally published on Westwood Horizon on October 30, 2023.