The diagnosis took months.

Pacing back and forth was common in the Guinan household as they awaited the results.

The parents found themselves in a confusing and chaotic world as doctors shared important information that they were completely unaware of.

Jenny and Ollie Guinan found themselves enveloped in a new world of confusion and worry as their first son, Mannix, was diagnosed with autism and ADHD, changing their lives forever.

Early Intervention:

On March 1, 2016, Mannix Guinan was born in suburban San Carlos, California, where he spent his early years with his parents, Ollie and Jenny Guinan.

“We didn’t see anything out of the ordinary for the first few years,” Jenny said. “Because Mannix is our firstborn, we didn’t have a blueprint to go off of in the first place.”

According to the National Institutes of Health, many children show symptoms of autism from twelve to eighteen months of age. Still, it is common for children to fully express their autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) further into neurological development.

Even when COVID-19 spread throughout the area and forced kids to stay with their parents for the foreseeable future, Mannix’s symptoms went unnoticed by his parents.

“It was frustrating that we didn’t see anything earlier that would have helped him,” Jenny said. “It made us feel like failures as parents, even though there was no way we could have known.”

It was frustrating that we didn’t see anything earlier that would have helped him; It made us feel like failures as parents, even though there was no way we could have known.

— Jenny Guinan

Jenny and Ollie would get their first indication that Mannix had ASD with help from Trinity Presbyterian Preschool in San Carlos.

“We were first notified that he might need a specialized environment from the teachers at Trinity,” Ollie said. “We didn’t know what that meant for him, but their experience helped us move forward with this process.”

The preschool’s staff first pointed out that Mannix was severely behind his peers with lateral movement, meaning he had trouble coordinating movements between the left and right sides of the body, making balance more difficult.

“We started to notice that he completely skipped the crawling stage together,” Jenny said. “I assumed he was just naturally gifted, and I didn’t expect anything negative to come from it.”

The early process of evaluations truly set into perspective the fact that their son could be considered different from everyone else, frightening them as they didn’t know how to move forward.

“It was a real struggle having to take a step back and realize he was missing skills essential for life that didn’t develop early on,” Jenny said. “I never thought we would be put into this situation, but I knew we had to keep going.”

The Diagnosis Process:

ASD (autism spectrum disorder) is a relatively new term that was introduced in 2014 to describe the vast area of neurological disorders. Old terms such as Asperger’s and ADD (attention deficit disorder) were phased out and put under ASD’s figurative umbrella but still find their way into our vocabulary.

“When we were growing up, words like autistic and retarded were used derogatorily in most cases, and we didn’t know what they meant,” Ollie said.

When the diagnosis process first began in 2021, the Guinans felt like they were thrown into a new world, as nothing in their past had prepared them to become experts on the autistic spectrum.

“The experts involved in his diagnoses kept recommending programs to us, and we were not experts, so we had to trust what they were saying, which was scary in a way,” Jenny said.

As the evaluation continued, experts recommended putting Mannix into a special program.

“I felt a lot of fear when we were still going through the beginning stages that his peers wouldn’t accept him,” Jenny said.

Sue Thompson, a program manager at Trinity Presbyterian Preschool, supported the family in the first stages of evaluation, which took about a month, before starting the official diagnosis process.

Thompson takes it upon herself to introduce parents with recently diagnosed children in San Carlos to their community of parents in the same situation. Thompson’s experience as a Parent with a child with epilepsy gives those parents the opportunity to have an expert in this field on their side.

“I remember how blindsided I felt when I first found out my son had epilepsy, and I wanted to reach out and help other families that were going through this process for the first time,” Thompson said.

The diagnosis can be a stressful time for new parents who are unfamiliar with the process, as about 50% of marginal fail due to this reason.

“Parents often start to shift into a kind of scientist and doctor and become fixated on helping their kids, which can make them very protective of their children,” Thompson said.

As parents start to gain their bearings and create a new way of life centered around their children’s needs, structure and education become crucial for their development.

The Importance of Structure and Education:

“The largest change in our lifestyle is structure,” the Guinan parents said. Part of Mannix’s official diagnosis was the add-on of ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder) on top of ASD, which was diagnosed earlier.

“They noticed the symptoms of autism before ADHD,” Ollie said. “We noticed that he was always playing with something and fixed on random objects, changing how we taught him in the future.”

“You can’t spring things on Mannix,” Jenny said, “We have had to create a structure that we explain to him an hour or a day before we do something, or it becomes overwhelming for him.”

Despite Mannix’s enjoyment of interacting with others, social interaction is a large part of the additional support he receives at school.

“Mannix spends much of his time almost in his own world; he’s very happy on his own, speaking to himself and imagining in his head,” Jenny said. “Luckily, the school district has a very strong belief that they want every one of their students to be able to access their environment.”

One of the largest worries that the Guinens faced early in his education was the fear that Mannix would be separated from his peers, hindering his development.

My deepest fear is that he would absolutely be ostracized and made fun of and that people would see that he was different, make fun of him, and bully him.

— Jenny Guinan

“My deepest fear is that he would absolutely be ostracized and made fun of and that people would see that he was different, make fun of him, and bully him,” Jenny said.

From the low-stakes environment of preschool where everybody is developing together, Mannix transitioned to Heather Elementary School, where gets the opportunity to participate in classes with the rest of his grade.

“Unlike the one special education classroom we were used to in the past, Heather Elementary School has a more fluid system that allows other students to interact with the specialized classroom and vice versa,” Jenny said.

A defined structure at school allows Mannix’s parents to be in regular contact with Mannix’s teachers and change their program to fit the person he’s becoming.

Moving Forward:

As Mannix grows older and moves up in school, Jenny and Ollie face the delicate task of telling him that he’s on the spectrum.

“It’s like he already knows that he’s a little bit different than everybody else, but I struggle with telling him because I don’t want to say the wrong thing and confuse him even more,” Jenny said.

Living in San Carlos gives Mannix a significant advantage over others because of the area’s access to resources, allowing for more expansive programs that support special needs children’s development.

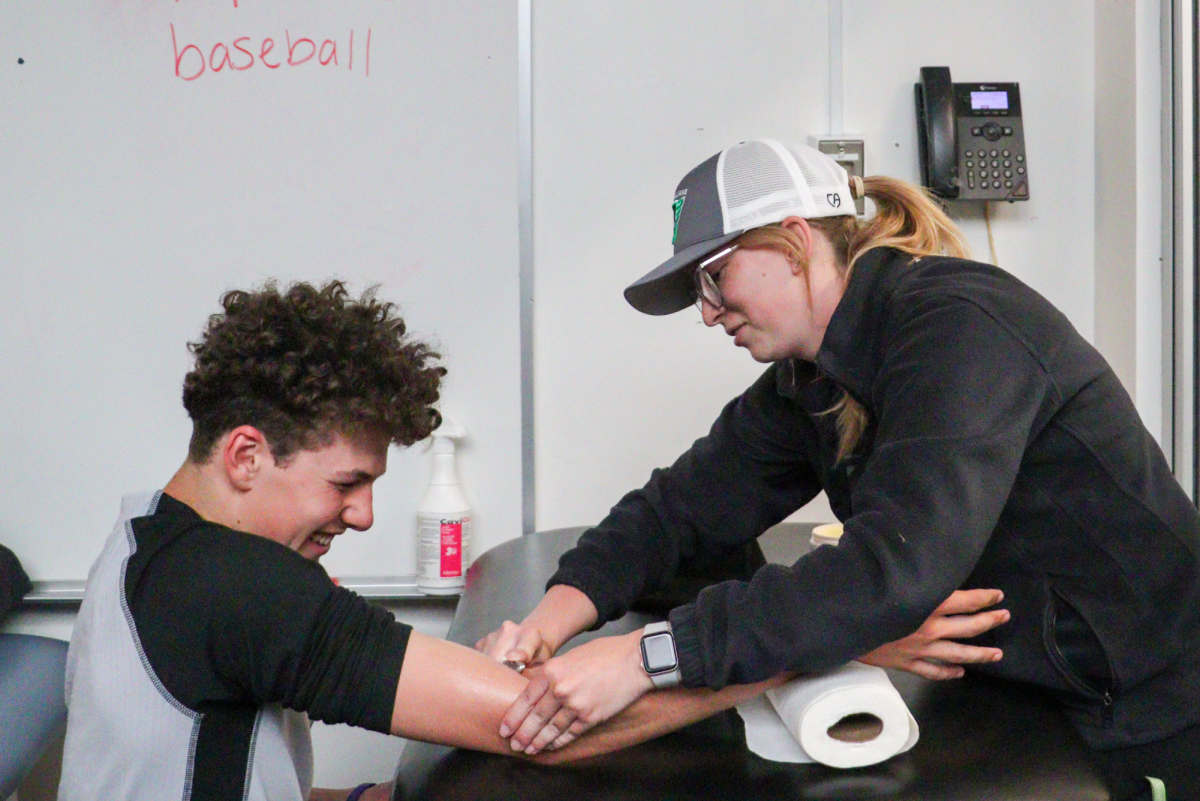

One option that Mannix has in his future is going to Carlmont High School, where he would meet Justine Hedlund, a special education teacher at Carlmont.

“High school is a different environment than elementary or preschool because people are more neurologically developed,” Hedlund said.

Mannix’s future, like everybody else’s, will be filled with stressful situations that he will have to overcome.

This story was originally published on Scot Scoop News on January 12, 2024.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)