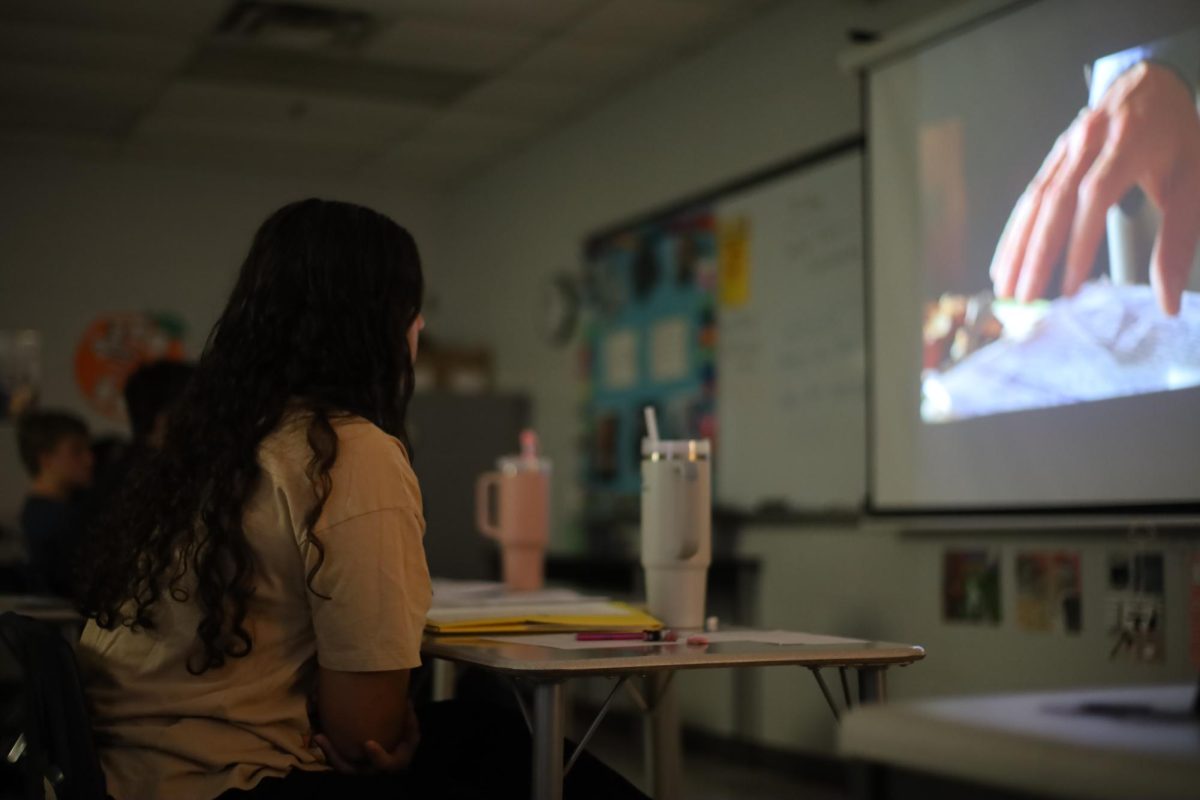

When film teacher Jaimie Ling first heard about the district’s new movie restriction policy, her first thought was, “Oh no, here we go.”

Last December, Seminole County published new guidelines for educational material, requiring that all movies be watched and approved by the school principal and certified media specialist. Teachers who do not follow the policy are in direct violation of the law and will be subject to investigations that may result in the loss of their teacher certification. Considering the hundreds of teachers on campus, principal Robert Frasca found the new policy impossible to enforce.

“I 100% understand the intent of [the policy], and I absolutely support the fact that we should be using appropriate materials,” Frasca said. “It’s the execution that’s become impossible…to expect that a principal could read every book, watch every movie and everything that gets shown is just an impossible task.”

In the advanced film class alone, students watch 35 movies throughout the school year, most of which are rated PG-13 or R. Permission slips have long been standard procedure in such classes, as teachers anticipated state and parental objections.

“For the 15 years I’ve been teaching film, I have always sent out permission slips. I’m not going to show a rated R film just because I like it…I’m going to teach it because it has academic merit in regards to film analysis,” Ling said.

Thanks to the foresight to send out detailed permission slips in previous years, film classes will proceed as normal this year.

However, other classes are not as fortunate, with the new restrictions forcing teachers to rework certain assignments. AP Literature teacher Cameron Curran often shows screen adaptations of class novels, such as “Macbeth” and “Fahrenheit 451,” to help her students understand the literature better and connect with it on a deeper level. With movies, and even YouTube clips, now in question, Curran’s students miss the opportunity to consume the material in their intended form.

“[Pieces like “Macbeth” and “Hamlet”] were never meant to be read. They were meant to be viewed as plays and performances,” Curran said. “So now to have a law that suggests that I’m unable to show these classical pieces of literature modernized and made relevant…it’s very disheartening.”

Language classes have also felt the brunt of the new legislation, as the vetting process is nearly impossible with their material in a different language. In French, students often watch films to help them understand the culture and language better. French teacher Pamela Lynch worries about the more long term effects of the policy.

“I don’t understand why we’re not allowing kids to learn any kind of culture…it’s going to make us more isolated as a state,” Lynch said.

Junior Macy Drewry, who takes French III, was disappointed when she heard the new policy prohibited the class from watching “Ratatouille” dubbed in French, a tradition she had been looking forward to since freshman year. She was especially perplexed considering the movie’s G rating and reputation as a wholesome family film.

“I’m confused why this policy is needed because I would think that movie permission slips are enough,” Drewry said. “I understand that there may be sensitive content…but if the teacher requires a permission slip, I believe the teacher is not responsible if someone gets upset.”

The new policy comes in the midst of a school year fraught with increasing restrictions, from book bans to nickname permission slips. As the principal tasked with carrying out such laws, Frasca is frustrated at the ambiguity of the situation. Despite claiming “Florida legislation” as the cause of the new policies, the county guidelines do not name any specific bill in question, leading many to assume that the policy is a more cautionary measure than specifically ordained by the state. The guidelines are also vague on the fate of YouTube clips and whether lower rated movies, like G and PG films, are allowed to be shown.

Film teacher Lisa Gendreau believes the tightened policies are simply a byproduct of distrust in teachers, as some parents, bolstered by politicians, worry over “indoctrination” in schools.

“Instead of dealing with the teachers who have made bad choices [in the materials they choose to show], everybody’s suffering because [the higher ups are] micromanaging everybody,” Gendreau said. “I still get emails from former students that tell me how much they liked the class and remember it. It would be a disservice to students if something stopped my film class from continuing on.”

Although often marketed as an easy elective with little to no homework, Gendreau believes the real merit of the class comes from its ability to develop students’ critical thinking. As students are tasked with analyzing directors’ choices and iconic moments in American cinema, they learn more about themselves as well.

“Films are a great way to help students learn about life from a different perspective,” Drewry, who is also taking film class this year, said. “I believe the teachers mean absolutely no harm and are just trying to do their job for the benefit of the students.”

Although parents are often blamed for the rise in drastic policies, Ling points out that most parents work diligently with teachers to support their children. It is only the few bad apples that spoil the barrel.

My hope for the future is that we let educators do what they do best, which is to educate.

— Jaimie Ling, film teacher

County guidelines continue to be unclear about what the future holds, but Frasca chooses to take it one day at a time, planning for next year based on feedback from teachers and other principals in the county. Even with the overwhelming nature of the situation, he trusts teachers’ perseverance will pay off in the end.

“Educators have always found a way to overcome every challenge that is thrown their way because they love their kids. And I do believe that in the end, our staff will find every resource they can to continue to make great educational experiences for our kids,” Frasca said.

This story was originally published on Hagerty Journalism Today on January 16, 2024.

![It was definitely out of my comfort zone to get [the dress] and decide I loved it enough not to wait and risk not having something that memorable.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Precious_20180902_JRS_00008_ed1.jpg)

![Sophomore Sahasra Mandalapu practices bharatanatyam choreography in class. These new dances will be performed in an annual show in February. Mandalapu found that practicing in class helped her overcome stage fright during her performances. “When [I] get on stage, Im nervous Im going to forget, even though Ive done it for so long,” Mandalapu said. “Theres still that little bit of stage fright [when] I second-guess myself that I dont know it enough, but I do because Ive been practicing for a whole year.”](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Sahasra-6-Large-1200x844.jpeg)

![In their full runway outfits, (from left) Audrey Lee 25, Olivia Lucy Teets, 25, Fashion Design teacher Ms. Judy Chance, and Xueying Lili Yang pose for a photo. All three girls made it to Austin Fashion Week by getting in the top 10 in a previous runway show held by Shop LC.

[I like my students] creativity and how they can look at a fabric and make it their own, Ms. Chance said.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_9686-e1714088765730-1129x1200.jpeg)

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)