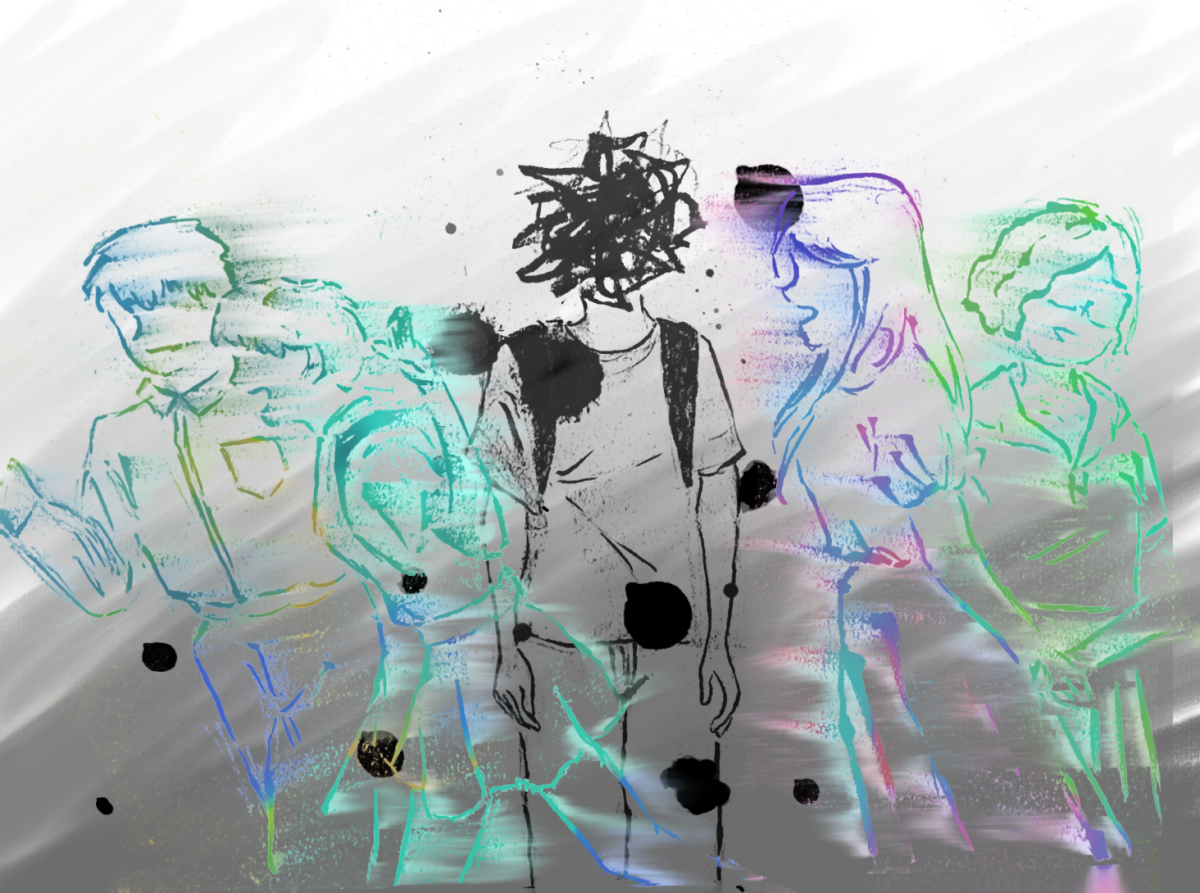

For some, the onset of winter conjures feelings of excitement and festivity — holiday dinners with family, sledding over winter break, sleeping in on the occasional snow day. Yet, for others, the colder temperatures and early darkness bring a sense of dread and depression. Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) is defined by feelings of persistent sadness and apathy triggered by the change of seasons that goes beyond the typical “winter blues.” SAD’s symptoms align with those of depression but are correlated with seasonal changes.

AP Psychology teacher Travis Henderson has struggled with SAD since third grade. His seasonal depression typically manifests as an increase in lethargy and diminished motivation.

“[During the winter], I withdraw a little bit. I don’t want to go out as much … I just want to stay home,” Henderson said. “Feelings-wise, it’s like a pit [or] hollowness in my chest. When that feeling comes around, I’m like, ‘Oh, must be winter.’”

Henderson experiences bouts of depression throughout the whole year, but winter is significantly worse for his mental health. However, for Catherine Yang ’23, a former West student and current freshman at Carnegie Mellon University, her feelings of depression are confined to only the winter months.

“I’m generally pretty good at identifying what I feel. I feel weirdly apathetic and lonely during the winter,” Yang said. “I thought that was normal, but I found out it’s actually not. People usually feel pretty much the same in the winter.”

For an anonymous student source, who has been dealing with SAD since junior high, the change in weather around the end of fall spurs feelings of dread about the coming months.

“All of a sudden, six o’clock hits, and the sun’s starting to set. It’s just that slight reminder that it’s going to be cold all the time and the sun’s never going to be up,” the anonymous source said. “[In the winter], I’m always exhausted. I get up before the sun has risen, and by the time I get home, the sun’s been set for four hours. So, I feel like I’ve had a whole day of just nothing.”

Researchers speculate that SAD is tied to a lack of sunlight, which impacts biological systems like the circadian clock and the secretion of hormones like serotonin. Fewer UV rays may also induce an overproduction of melatonin, a hormone responsible for drowsiness.

Dr. Adam Woods, a family psychiatrist at Gersh, Hartson, Payne, Hoffman, & Associates, emphasizes that increased fatigue in the winter months is not unique to humans and has an evolutionary component.

“We’re animals just like every other mammal. So what is every other mammal in nature doing in the winter? They’re sleeping more, eating more, and they’re not as active as they were,” Woods said. “Only the human animal believes it needs to be just as active in December as it is in July.”

Yang observes that her seasonal depression is marked by fatigue, making it difficult to get out of bed.

“When I’m feeling depressed, I just stay in bed forever. I know there is stuff that I should be doing, but I don’t remember why I should care,” Yang said. “The very basic things are a struggle; there have been periods of time where I don’t eat because I’ve been sleeping so much.”

Henderson also identifies his desire to stay in bed as one of the biggest challenges of his experience with SAD.

“I wish I had the energy and gumption to enjoy things. [During Thanksgiving], I really wanted to enjoy [being] around my friends and the time off,” Henderson said. “[But] I just wanted to be in bed.”

Another component of Yang’s SAD is overthinking, which can be detrimental to her relationships.

“I’ll lay in bed, and I’ll just think about my life or the choices I’ve made or some dilemma that really doesn’t matter. But in my mind, at the time, it seemed really important,” Yang said. “I start overthinking all my relationships, all the tiny things that normally I don’t care about.”

Though the symptoms of SAD can be overwhelming, many treatment options are available for those experiencing the disorder. Talking to a mental health professional, taking antidepressant medication and getting more light exposure are all common therapies.

Woods cites the benefits of a light box, which delivers fluorescent light without harmful UV rays, mimicking the effects of sunlight. He also acknowledges the importance of slowing down and finding time for self-care.

“The five things … for [improving] mental health are therapy, sleep, diet, exercise and meditation,” Woods said. “If you need to sleep more, sleep a little more. If you want to eat a little more, eat a little more; don’t judge yourself.”

Henderson employs a multi-faceted treatment approach to combat his SAD.

“I have to be much more conscientious about getting to the gym when it starts getting cold outside because that really helps balance my mood,” said Henderson. “I will go tanning … I’m there to just get some UV rays… the benefits are so great for me that it justifies the risk. I [also] have ongoing conversations with my doctor about adjusting my meds.”

Although seeking help is important, it can be difficult. For Yang, the logistics of finding time to schedule and attend a therapy appointment have kept her from doing so. However, she still makes sure to prioritize her wellness.

“I do a lot of self-care. I journal everyday — I’m a creative writer, so I write occasionally,” Yang said. “I do extra, random skincare steps if I’m really feeling it.”

The stigma surrounding men’s mental health also creates barriers to receiving professional help. Social pressures and a lack of accurate media representation of depression have made the process of reaching out and the required vulnerability uncomfortable for the anonymous source.

“There’s a lot of stigma around men’s mental health … and that’s also a big factor of not going and getting [help],” the anonymous source said. “There’s no one directly next to me where I’m like, ‘I think I should go to therapy,’ and they’re like, ‘What a loser.’ It’s more [that] I’ve seen so much in media, and people around me are like, ‘No, I’m not gonna go to therapy; men don’t go to therapy.’”

Still, Henderson emphasizes the importance of validating the impact of SAD and receiving support.

“It’s powerful to name what you’re experiencing. Be honest about what you’re experiencing,” Henderson said. “It’s powerful to seek help. It’s not something that you have to just deal with every November and December, [whenever] your time period is. It’s not something you just have to labor through.”

This story was originally published on West Side Story on January 22, 2024.