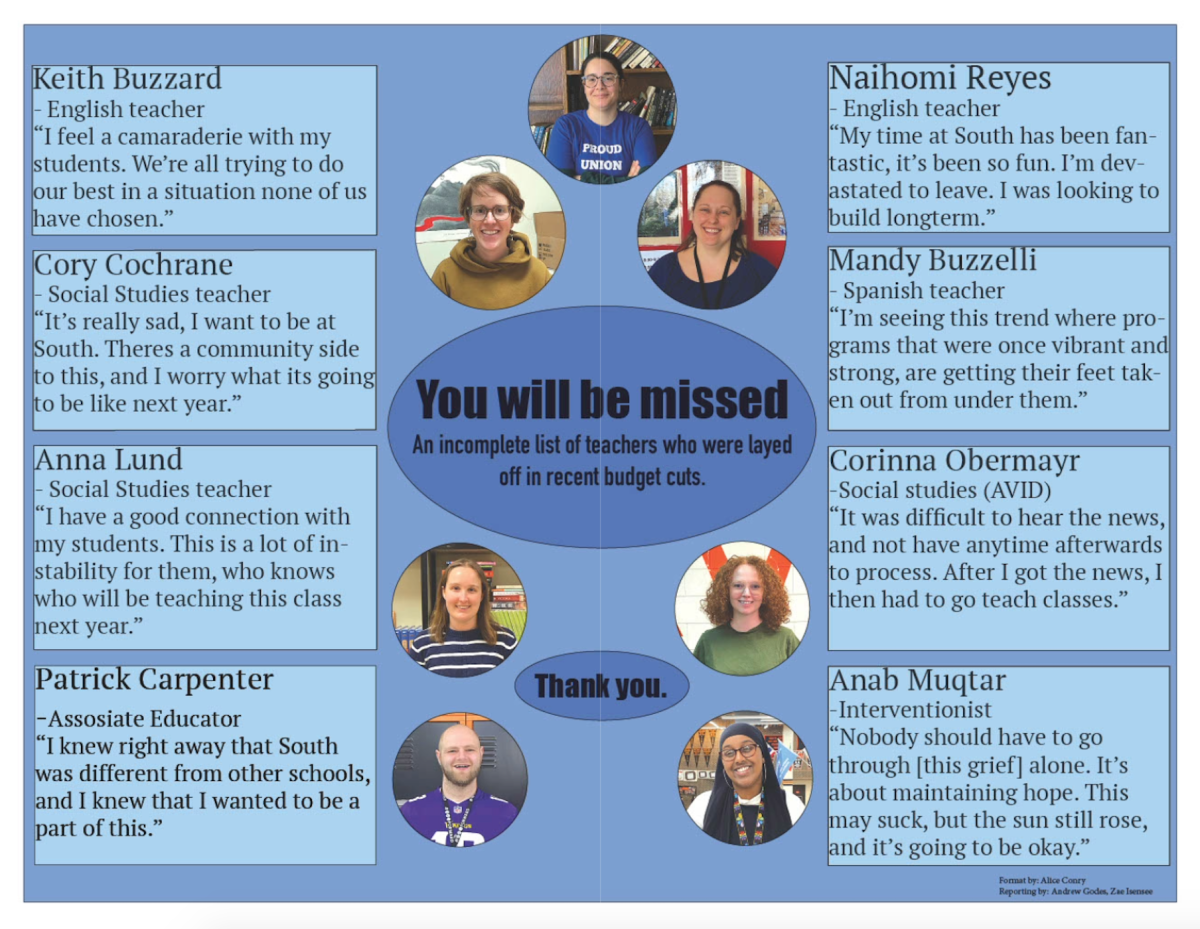

Throughout the second week of March 2024, teacher after teacher was called into the office to meet with South principal Afolabi Runsewe. As teachers came into the office, their anxieties were low, expecting the routine yearly questions regarding their renewal status and plans for the coming year. Many of these teachers, to their surprise, they learned that due to $2.8 million cut to next years budget they would be excessed.

The new provisional budget outlined by Principal Runsewe for the 2024-25 school year entailed the non-renewal of over 25[a] teachers, an unprecedented figure in years past, even amidst other large cuts to the school budget. Average projected class sizes for the coming year, along with individual teacher workload, skyrocketed. Teachers were taken aback, scrambling for alternatives for employment and answers.

In large part, the unprecedented nature of this provisional budget reflects a greater turmoil regarding the new Minneapolis Public Schools budget.

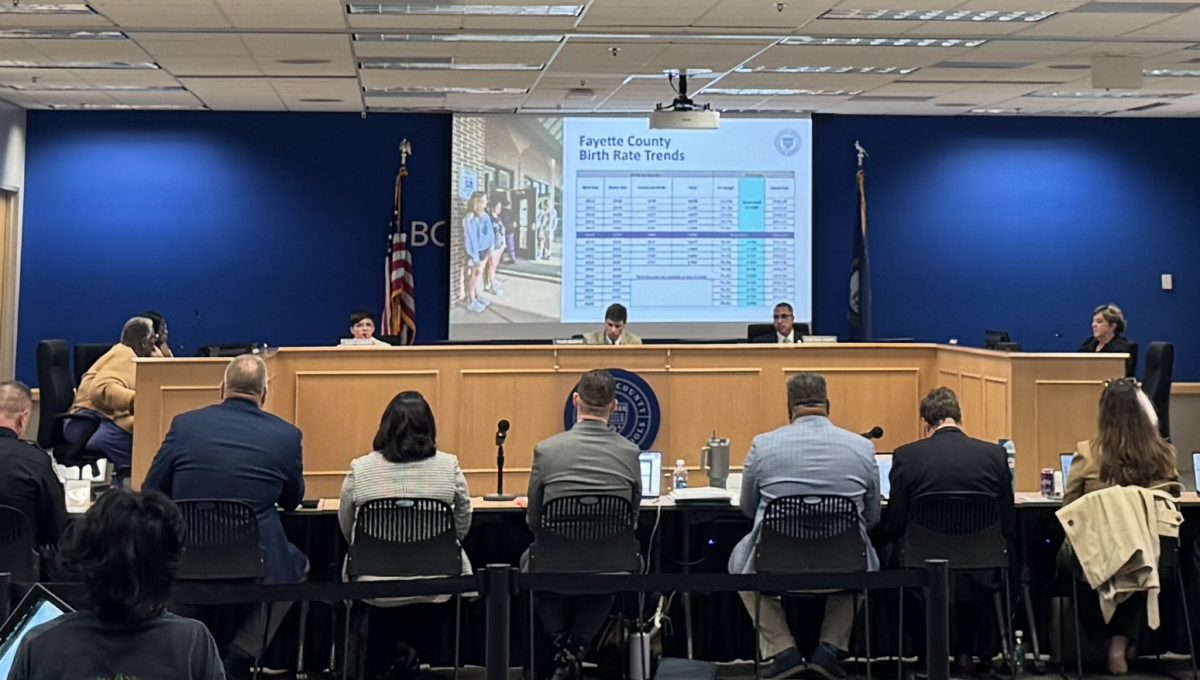

On March 1, 2024, MPS principals were collectively informed by the district of a projected $110 million cut in its budget, effective the upcoming 2024-2025 school year. The cuts reflect the expiry of COVID-related emergency funding measures, a crucial source of income. Principals at each school were theoretically responsible for deciding what staff members were cut accordingly. Yet in practice, due to certain contract obligations, they had little say in the matter.

Particularly, order-of-nonrenewal policies such as order-of-seniority, (younger teachers get cut first,) and initiatives to reduce firings of teachers of color, (the latter brought about during 2022 strike negotiations,) meant that effectively, Principal Runsewe had little actual say in who gets cut and who does not, other than following the rules laid out for them by district-level contract language.

These contractual clauses quickly became the subject of frequent debate at South amongst students. The seniority-order clause, in particular, gained some scrutiny, as the student base questioned the effects that losing the school’s youngest teachers – and those closest to students in age – would have. Contract language around retention of teachers became a source of confusion as well, as it remained unknown how administration would weigh this contract language against the aforementioned seniority guidelines (i.e. how administration would choose between letting go of a younger teacher of color vs. an older non-teacher of color).

One aspect that principals, including Runsewe, did have more agency over is the areas the cuts would target. Principal Runsewe, in particular, opted to defer the decision to families, releasing a survey for families of different backgrounds to fill out regarding which areas of staff were most important to them, and which would be the greatest losses if cut. The results of these surveys generally indicated that families prioritized safety and mental health and academic support. As a result, cuts affected teachers as opposed to counselors and the engagement team.

Despite the lack of precedent for these cuts, and confusion about the specifics about them, in a wider sense, these cuts came as no surprise to those familiar with the landscape at South. Student enrollment – due to various factors, such as safety concerns, redistricting, and the pull of charter schools – had been trending downward for several years.

Since 2019-20, the size of the freshman class has already been nearly cut in half. A wave of cuts and a decrease of funding was largely inevitable to some extent, in order to meet the needs of a declining number of students. Even then, however, a cut of $2.8 million – the amount cut from South by the district budget – seemed to be a disproportionately large figure, despite the difficult circumstances.

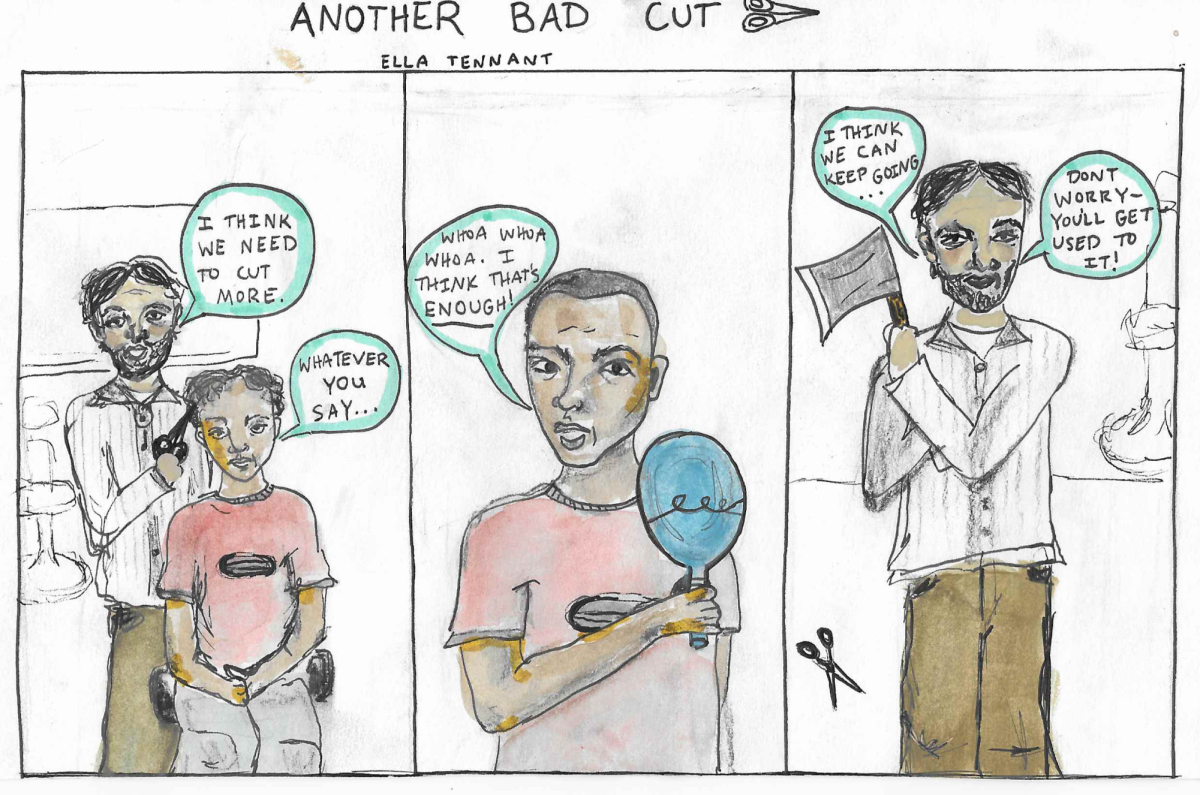

The overwhelming feeling that remains at South, amidst the preexisting and growing student retention problem at the school, is that these budget cuts are an incredibly large punch while South is down. The effects of these cuts to the budget – increased class sizes decreasing individual attention for students, less elective options for students to tailor their education through, and so much more – will only further incentivize students at the school to transfer elsewhere, and disincentivize incoming 9th graders and their families from choosing South. And the student base decreasing further, of course, serves as justification for further budget cuts, further layoffs, and the cycle to continue.

Looking forward, administration and MPS have a large task on their hands in turning around the gloomy trajectory that South seems to be headed in, and in lieu of the aforementioned challenges and waning optimism surrounding the school, it’s vital to keep in mind what South is about.

For 139 years and counting, our school has been home to South Minneapolis’ student base, laying claim to the title of Minneapolis’ oldest high school. Its range of backgrounds and cultures has made for a uniquely inviting, diverse, and tolerant school environment, serving as a safe space for countless marginalized students to be themselves everyday. It’s a community that has molded generations of students into the people and professionals they are today, and above all, South is worth the effort.

This story was originally published on South High School on April 9, 2024.

![Finishing her night out after attending a local concert, senior Grace Sauers smiles at the camera. She recently started a business, PrettySick, that takes photos as well as sells merch at local concert venues. Next year, she will attend Columbia Chicago College majoring in Graphic Design. “There's such a good communal scene because there [are] great venues in Austin,” Sauers said. “I'm gonna miss it in Austin, but I do know Chicago is good, it's not like I'm going to the middle of nowhere. I just have to find my footing again.” Photo Courtesy of Grace Sauers.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Grace.png)