Pharmacologically perplexing theories permeated freshman Shripriya Kalbhavi’s mind as she sat pensively, cross-legged on her bedroom floor, pressure transducer ready to calibrate, marking the next brave leap into her scientific creation.

At 14 years old, Kalbhavi developed EasyBZ, a cost-effective microneedle patch that allows for the transmission of drugs without the use of traditional or hypodermic needles.

In eighth grade, Kalbhavi won second place in the 3M Young Scientist Challenge, a project-based contest for students in grades five through eight to describe an innovation or solution to an everyday problem that addresses an issue they are passionate about. After winning a $2,000 prize for her submission video of EasyBZ, which outlines her purpose and process of creating the patch, Kalbhavi was featured in many articles for her achievement. One in particular, published on March 8 by “American Kahani” magazine, named her an “Indian American Trailblazer” in honor of International Women’s Day, along with others such as Vice President Kamala Harris and British Indian actress Ambika Mod.

“Winning second place was surreal to me,” Kalbhavi said. “It gave me a lot of perspective into how many people could potentially be impacted by this patch. I am excited and hopeful for its future developments.”

As a young child, Kalbhavi was one of many with Trypanophobia, a fear of needles. She was determined to explore a painless alternative to disease prevention, one that challenged the norm of traditional vaccines.

“Hypodermic needles are really painful and invasive, and they require someone to actively administer them,” Kalbhavi said. “My main idea behind this was to make it easy to use autonomously, especially because many people I am targeting as the end users are older adults and younger children with diabetes.”

The patch itself is composed of microneedles — minuscule, painless needles that penetrate the skin — along with a Belousov-Zhabotinsky (BZ) gel, a radically swelling polymer hydrogel. This substance oscillates, generating pressure, which is used in the active medication component of the microneedle patch.

“My experiment was originally from a process called the BV oscillating reaction, but it can also be adapted into hydrogels, which is the bulk of what I worked on,” Kalbhavi said. “I was able to bring the idea to life by experimenting with different hydrogels and materials to observe their compatibility in the patch.”

The patch is simply placed on a patient’s skin and activated, allowing the reactants of the BZ gel to mix and induce the gel to swell and shrink in size, thereby forcing the medication into the skin through the microneedles.

“I’ve always been interested in the intersection of biology and chemistry, which I actively studied in my experiments,” Kalbhavi said. “I think there’s a lot that both fields can learn from each other.”

After being selected as a finalist for the 3M Young Scientist Challenge, Kalbhavi was matched with a mentor, Dr. P.J. Flanigan, a central resource manager for 3M Healthcare, to help make her patch a reality. When creating EasyBZ, Kalbhavi considered its cost, how easily it could be manipulated, the fact that it could be contained in a small space and other design features.

“My mentor was really helpful; she gave me a lot of insight into the medication delivery field,” Kalbhavi said. “She was able to talk to me about the different challenges people face, having worked with transdermal patches before.”

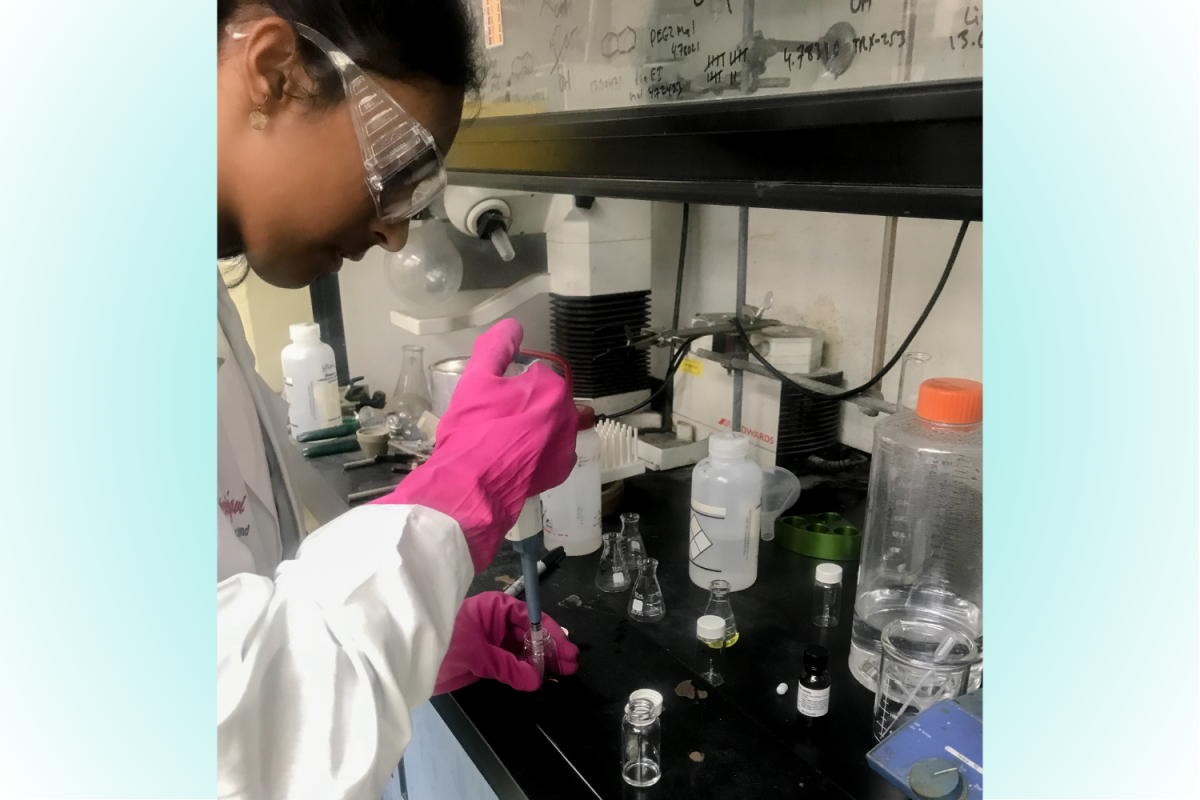

Nevertheless, Kalbhavi’s experimental process was daunting from the get-go. Acquiring laboratory space as a freshman in high school is no easy task. She considered performing the lab work at home, but many of the chemicals she worked with required the safety of a lab setting. After months of reaching out to private research labs, one of them happened to say yes.

With the help of her plexiglass prototype, Kalbhavi sought to make a bona fide version of EasyBZ involving a BZ reaction, polymerization and pressure transducer calibration. She was initially nervous, unsure EasyBZ would become a reality because microneedle drug patches fall under a relatively untapped field.

“When I talked to many scientists, they all told me, ‘Ok, this idea’s kind of nuts,’” Kalbhavi said. “But they said we could give it a shot.”

Kalbhavi felt frustrated at times when certain aspects of her experiment did not go as planned. At one point, she tried to recreate one of her reactions, which “completely refused to work,” Kalbhavi said.

“The whole process of going back, figuring out what went wrong and fixing it was both exciting and frustrating,” Kalbhavi said.

Her efforts came to fruition following months of experimentation, and Kalbhavi saw enthusiastic support from her parents and younger sister for her second-place win.

“A lot of my friends also watched the live stream during the final event and were super excited to see what came out of it,” Kalbhavi said.

But Kalbhavi hasn’t stopped there. She hopes to formally patent EasyBZ, having received her provisional patent a few months ago. She plans to apply for a nonprovisional utility patent to protect the design idea, eventually gain FDA approval and start clinical testing on its journey to public usage.

“I think that my patch would help a lot of people since needle phobia is a pretty big deal with 2 in 3 children and 1 in 4 adults being afraid of needles,” Kalbhavi said. “Getting it out into the market and having it available for use would really change a lot of lives.”

Furthermore, as a woman of color and young scientist, Kalbhavi continues to find similar role models and encourages all young aspirants to do the same. She hosts a podcast called “Famous Personalities,” where she speaks about the lives, achievements and research of female scientists.

“A lot of the reason why you don’t see a lot more young women getting into science is because they don’t have enough role models to look up to,” Kalbhavi said. “My mentor was the epitome of the role model that I wanted as an adult in science; I think my advice for anyone wanting to get into science would be to look for a role model who reflects them as a person.”

Kalbhavi hopes to contribute to innovation in the future as a neurosurgeon or other medical professional, but she wants to keep her options open. For now, she simply wants to go into a field that helps others.

“Science is really open to anybody that wants to get involved,” Kalbhavi said. “It’s a great way to give back to your community and I’ve found that it can inspire people in all sorts of ways.”

This story was originally published on The Epic on April 1, 2024.