“I resisted journalism,” Jeffrey Gettleman (P ’27 ’30) said. “I had a teacher in college tell me, ‘You seem to like writing. What about working for a newspaper?’ and I said to him, ‘Who would want to work for a dumb newspaper?’”

Growing up, Gettleman, now a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, knew he liked to write. Gettleman said the role of words in telling stories always intrigued him.

“I liked to write as a kid,” he said. “That was always, in school, like, my strongest subject. That was where I felt most natural and interested.”

Gettleman said his passion for writing evolved alongside his lifelong love for reading.

“As a kid, I read a lot of fiction and short stories, and I liked that,” he said. “I remember being in high school and getting a light bulb in my head when I read a book that I really connected with.”

Education

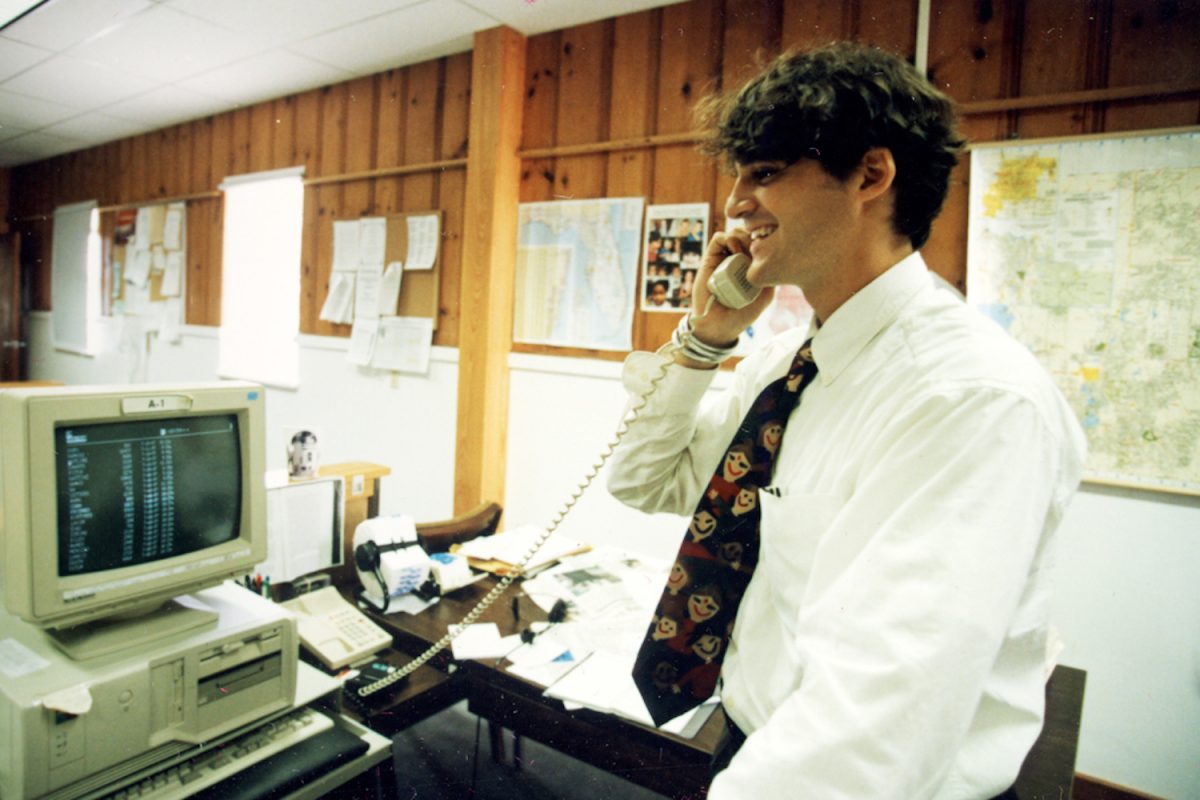

After graduating from Evanston Township High School in 1989, Gettleman attended Cornell University, where he majored in Philosophy. Gettleman said pursuing journalism was not his primary goal as a student.

“I wasn’t one of these students who work[ed] for the student newspaper,” Gettleman said. “I hadn’t done that, but I thought journalism would be, like, a way to unite different interests.”

In a yearlong pause from finishing his degree, Gettleman traveled the world with his friend and a backpack. Starting in the U.K., Gettleman traveled through Europe, the Middle East, Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia — a period of adventure he said allowed him to experience the world in an interesting way.

“We did that for a year, with no structure, no supervision, just kind of exploring,” he said. “Then, I went and finished college and I was able to take some languages and some courses that I had discovered on my trip.”

However, after returning to complete his degree at Cornell University, Gettleman said he was still unsure of which career he wanted to pursue.

Nevertheless, Gettleman later received a Marshall Scholarship, an award granted to postgraduate Americans that enables them to study for two years in the U.K. His decision to study at Oxford allowed him to continue exploring his variety of interests before settling down.

Before starting his master’s degree, Gettleman spent his summer in Ethiopia, where he worked on a newsletter for Save the Children, a charity offering children a healthy, safe start to life. Gettleman said the poor conditions of the country were evident from a simple walk down the street.

“There were bodies of dead animals on the street, there were lots of homeless people, lots of kids that are orphaned,” he said. “This whole place was very broken, and my job was to work with street children, kids that had no parents, that were living on the streets. They were sniffing glue, they were wearing rags, they were in really bad shape.”

Gettleman said the trip was a pivotal moment in his career and what piqued his interest in journalism.

“I was 22 years old, and I was in the middle of this interview with a guy about a street children project,” Gettleman said. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, this is really cool. Maybe I should be a journalist.’”

East Africa

After visiting East Africa for the first time, Gettleman said it felt as if he was experiencing a new world.

“It was like taking me out of a black and white film and putting me in the brightest, most saturated colors, like, everything was interesting,” he said.

Reflecting on his travels through East Africa, specifically Malawi in 1990, Gettleman said he was moved by the sight of individuals who had close to nothing.

“These kids didn’t have shoes, many people were wearing rags, like, people didn’t own much,” he said. “They lived in small houses, with, like, very little, like … a spare set of clothes if that.”

From his travels to East Africa, Gettleman said he learned there was “so much more to the world than what [he] had known.”

“Despite that poverty, there was, like, this immense sense of community and openness and warmth,” Gettleman said. “You could talk to somebody and just, like, shake hands and hug and, you know, talk about whatever you wanted to and there was, like, a welcome, and a spirit that I felt.”

Moreover, Gettleman said his eagerness to work in East Africa persisted while starting his journalism career.

“I really loved East Africa,” he said. “It meant a lot to me. I studied Swahili … It really, like, stimulated me and excited me and just gave me a sense of meaning.”

After Gettleman began his first job as a journalist in Brooksville, Florida, for the St. Petersburg Times, he said his primary goal was to bridge journalism with his newfound love for Africa.

“I was trying to bring together these two things that were very different because I’m working in a little town in Florida, and I have this, you know, ambition to be working in East Africa, and they’re very different,” Gettleman said. “Nobody in this town in Florida was interested in Kenya or spoke Swahili, and people in East Africa have no idea about these little towns.”

Several years later, when Gettleman landed his first job in East Africa as a reporter for The New York Times, he said it was a “dream come true.”

“I was just very passionate and determined to do the best work I could, to take big risks, to just spend so much of my energy trying to tell the best stories I could,” he said. “The most important stories I could, in my way, were about people. People in crisis, trying to put a human face and motion into these bigger events that can get kind of confusing.”

Specifically, Gettleman said he enjoyed transforming people’s stories into words for others in different parts of the world to read and empathize with.

“You could be just thrown randomly into one of these countries,” he said. “Who would you become? What kind of person would you be?”

Life as a journalist

Gettleman said his path to journalism was not entirely straightforward.

“I still, you know, considered working at an investment bank and doing lots of different things,” he said. “I liked the idea of journalism, but I wasn’t sure even years into journalism.”

Moreover, Gettleman said his regular international coverage stemmed from his eagerness to travel.

“I really like traveling,” he said. “I like fresh places. I really get a thrill out of stepping off a plane, like, even today.”

Gettleman said the key to authentically reporting on a place is getting to know it in its entirety.

“Being, like, a good journalist, being an enthusiastic journalist, you’d have to be curious,” he said. “You have to know, like, what are you really thinking? You know, what’s your life like? What are you interested in? What’s going on in this place? Why is it like the way it is? What’s its history? What’s its future?”

Alternatively, Gettleman said covering countries undergoing severe conflict and learning about the lives of its people can be hard to digest, especially when he interviews people who have been personally affected.

“It’s very hard to cover trauma and conflict and bloodshed and suffering without it just leaving you really depressed and angry and feeling helpless,” Gettleman said. “That I deal with all the time, and it’s hard. Like, I interview people whose kids have been killed or whose parents have been killed.”

As such, Gettleman said reporting with accuracy and depth while maintaining deadlines can be challenging.

“You’re trying to describe things, you know, in a vivid way,” Gettleman said. “You’re trying to move readers, you’re trying to get the facts straight. You have all these notes and books and, you know, websites open, and you’re trying to figure out when this person was born and, you know, which direction this town is from another town.”

Love, Africa

After racking up years of experience writing articles for various publications, Gettleman yearned to try something new. He said he wished to write something at his own pace, leading him to start working on his first book.

“I had always wanted to write a book,” he said. “It was just a question of trying to find out, like, the time to do it.”

As a result, “Love, Africa” was published May 16, 2017. Gettleman said he wanted to write about himself, weaving together his experiences as a journalist and his growth as “just a normal guy.”

Gettleman said the book is a product of his desire to share how he felt while reporting and constantly sharing others’ stories.

“Most of the work as a journalist, you’re writing about other people’s lives,” Gettleman said. “You are the observer. You are not sharing how you feel so much.”

When working on his book, Gettleman said he often struggled to write about his feelings related to his experiences, as it was the first time he was the focus of his written narrative.

“The hardest parts were deeply personal things,” Gettleman said. “I wrote about my relationship with my wife, things that I had done that I regretted, mistakes I had made with that relationship. Those were hard because you’re trying to confess, like, some of your mistakes, and it can be painful.”

Nonetheless, Gettleman said he felt empowered by his newfound ability and platform to share his own story.

“There’s a value I felt to doing that because I want to share my story,” he said. “I want people to see me as a real person.”

Family life

Gettleman said his job often means working away from his family and home.

“For my work, it can get really hard because it can pull me physically away,” Gettleman said. “I don’t have an office I go to. I go to another country, that’s my office.”

As a husband and the father of two boys, Gettleman said he often regulates his career to make sure it does not negatively interfere with his personal life.

“The kids are in a totally different place, maybe a different timezone, and also like, [where I am] could be really dangerous,” Gettleman said. “I could be in a trench in Ukraine, or I could be on a battlefield in Congo.”

Therefore, Gettleman said reporting in areas of warfare means he must stay vigilant for his own well-being.

“I’ve got to just be paying attention to what’s around me, or I can be killed,” he said. “So, I’m not just away from home, I’m in, like, a different mind space.”

Gettleman also said he is committed to upholding his responsibilities to his family in his journalistic profession.

“I need to come back, I need to be there for my kids’ lives, I need to be there for my wife,” Gettleman said. “If something were to happen to me, that would be the worst thing I could do to my kids and to my wife … I don’t want to be causing sorrow and grief for the people closest to me.”

Winning the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting

In 2012, Gettleman was honored with an award for his reporting on the conflict in Sudan and Somalia: the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting.

Although he was proud of winning the award, Gettleman said the prize was not his ultimate objective when beginning his journalism career.

“That wasn’t like a specific goal of mine,” he said. “My goal was to work in East Africa as a journalist and sort of combine these interests I had in a specific part of the world with the work I really love doing as a journalist.”

Gettleman said the intention of his award-winning work was to inform the world about those suffering on a human level.

“These [conflicts], like, we would just talk about them as if there aren’t real people whose lives are being turned upside down,” Gettleman said. “I really wanted [readers] to feel the intensity and the suffering and the dignity of the people.”

Additionally, Gettleman said he reported on Somalia during a time of major upheaval.

“In 2011, there was, like, an explosion of problems in Somalia,” he said. “There was a famine, you know, the first major famine in decades where people are starving to death because they can’t get food. At the same time, there was this, like, very unusual piracy problem, where Somalis were going in little boats and attacking these gigantic ships floating in the ocean and taking the crew hostage and making millions of dollars.”

Consequently, Gettleman said in order to report accurately on the situation, he had to fully engross himself in Somali society.

“I’m not just going in and talking to you,” Gettleman said. “I’m reading books, and, when I get home, I’m doing research on the internet. I’m like, trying to study the language. I’m just trying to immerse myself in these places.”

Beginning in the early 2010s, the Arab Spring was a time of many uprisings and pro-democracy protests across the Middle East and North Africa region, according to Brittanica. Though many competing journalists chose to report there, Gettleman said his work in East Africa stood out.

“Somalia was a place not many journalists [were] willing to go,” he said. “That was one reason why I think I won, because I did work that was different, and it was about a place that had been neglected.”

Gettleman said the finalists of the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting were notified by phone of their decisions before the ceremony. At the time of the announcement, he said he was visiting his wife’s home in the U.S..

“I heard the voice of the Editor-in-Chief, and it was a woman at the time,” he said. “She had this very distinct, like, Boston accent, and she’s like, ‘Hello, Jeffrey.’ As soon as I heard her voice, I started crying because I knew … she wouldn’t have called me if I lost.”

Impact

Through his work, Gettleman said he strives to unite people and help them sympathize with the communities he writes about.

“As a journalist, you’re a bridge,” he said. “You’re, like, talking to this person in Congo, or in Ukraine, or someplace that is important at the moment, and you’re talking to them, and then you’re bringing that story to somebody that’s sitting in London or New York or wherever.”

Gettleman said his work has promoted action and support to improve the lives of people he has written about.

“I’ve written about women who were brutalized in eastern Congo, and, after I did that story, there was a whole effort to help those women to raise money and to set up charities and to really work on that issue,” Gettleman said. “It wasn’t me alone, but there were people responding to what I wrote that were moved to help.”

Through every interview and each sentence, Gettleman said he strives to change lives for the better.

“I didn’t get into this business to be on battlefields [or] to be in extreme danger,” he said. “That’s not what attracted me to journalism. What attracted me to journalism was seeing the world and telling stories and experiencing new worlds.”

This story was originally published on The Standard on May 23, 2024.