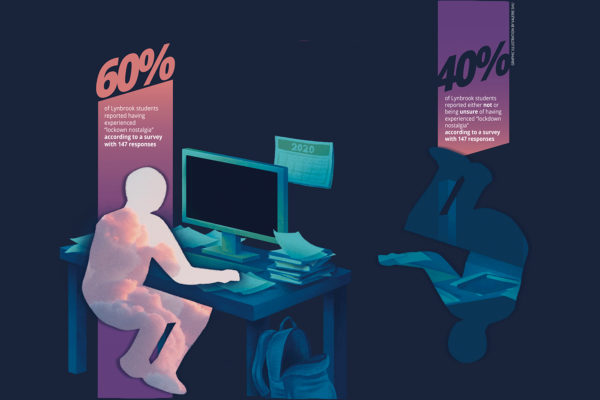

When pajamas, a bag of chips and a blanket were school-day staples, Zoom screens were dominated by various angles of student faces and ceilings and laggy voices emerging from computer speakers. These were common sights in the homes of millions of American students during the COVID-19 lockdown, where public health mandates required citizens to stay home and stay six feet apart due to the looming threat of the virus. In those days, streets remained empty, students jumped out of bed five minutes before school and spent their copious amounts of free time following online workouts or learning TikTok dances. Despite the ticking toll of infections from the virus and abundant boredom, four years later, many may find themselves yearning for those quieter times, as there seems to always be room for lockdown nostalgia amid frantic days.

As the months dragged on, however, many began to feel the effects of “pandemic fatigue,” caused by a weariness of following protective measures or registering public health recommendations from officials. Lockdown nostalgia grew from that period onward; people began longing for an idyllic version of the pandemic that most became exhausted living in.

“What I think has happened is that we as a community have processed our grief from that time. We’ve largely come to not only just acceptance, but finding meaning in it,” school psychologist Brittany Stevens said. “That’s really the most transcendent way to process grief is to think about what was maybe a positive or a lesson from it.”

Lockdown nostalgia consists of a longing for memories, habits and emotions experienced during the pandemic, usually in its early stages. Camaraderie persevered even when classmates were separated through Zoom screens and neighbors through their fences. Whether it was digitally hanging out with peers through apps like House Party and Among Us or taking frequent socially distanced walks, many teenagers found their free time accompanied by friends. An excess of free time also cultivated new at-home hobbies, including baking, crocheting, learning a new instrument or following new internet-viral recipes. Making sourdough bread was especially popular among those who took an interest in baking and whipped coffee became a daily beverage for those who partook in viral food recipes. A rise in internet use during the pandemic led to the popularization of various TikTok dances, trends and content creators.

“My classmates and I talk about how fondly recalling a time when people were struggling feels strange. For middle and elementary schoolers, distance learning was sort of an ideal period of time,” freshman Ceira Motoyama said. The pandemic produced mixed feelings for Motoyama, who recalls parents checking in during the day and feeling less isolated from family members compared to in-person school.

A universal sense of interconnectedness persisted throughout lockdown despite many being in isolated environments. Simple acts of kindness such as drafting letters for frontline workers and donations to local charities brought community service and volunteer work to the limelight — especially among students who had more time on their hands.

“I was able to really be tightly connected to a small core group of people, which is so different from the way most of us lead our modern lives,” Stevens said. “That is something I know people have nostalgia for and as well as the ability to have self reflection and think about hobbies you wanted to pursue. It forced people to become very creative with the limited resources that were available.”

Nostalgia is generally associated with positive memories, but it doesn’t always have to be a phenomenon of “rose-tinted glasses,” meaning a romanticization of the past. Finding a silver lining even amid the darkest moments is an optimistic human nature that can benefit mental health, which is a possible explanation for feeling nostalgic about quarantine. According to leading researcher on nostalgia study Kristine Batcho on the American Psychological Association, nostalgia can be a means to “keep track of things” and “monitor progress through life.”

“Something I’m nostalgic about is having the fun conversations with people I didn’t talk to as much pre-COVID-19, and staying up chatting, playing truth or dare and competing against each other on Discord bots,” junior Alexis Luo said.

The pandemic was a time for reflection and self-awareness for many. For the first time since many students’ busy schedules began in middle school, many were able to slow down and build on the person they wanted to become during the pandemic, whether it was starting new study habits, changing their style or starting daily affirmations.

“I was a sports athlete before the pandemic, so I had to keep myself moving while it happened,” sophomore Ariel Kuo said. “I had to have at-home workouts. I remember getting up and running around the neighborhood and sometimes in my backyard.”

Kuo also learned how to make slime using YouTube videos, utilizing materials at home such as shaving cream and glue. Additionally, Kuo had her first two pets, ducks named Guaca and Mole, which helped her grow as a responsible caretaker during the pandemic.

Pandemic nostalgia has been especially present across social media platofrms, with creators posting pictures of empty streets and the intimacy of home spaces at the height of the pandemic. Looking back at photos of mask art and family members embracing across sheets of plastic, a sense of peaceful solitude emanates from what otherwise might have been painful reminders of a briefly-dystopian world.

In school, the effects of lockdown nostalgia are easy to spot. Returning to a typical in-person high school can be overwhelming after one and a half years of receiving lessons virtually.

“There were some fun activities that I had my sophomores do that did really build community among them and their breakout rooms,” English teacher Jessica Dunlap said.

During the pandemic, there was no need for waking up early at 7 a.m. to prepare for school. Almost all homework was done and due virtually, while home-cooked meals could be enjoyed between class periods. These aspects of a more flexible home schedule were extended to both students and teachers.

“The thing that I miss is the asynchronous Wednesdays,” English teacher Jane Gilmore said. “There was an opportunity to rethink how we structure our schools which would allow teachers planning time with the trust that work is going to get done.”

The experience of the pandemic has changed not only aspects of life but of people as well. According to the World Health Organization, there was a 25% increase of anxiety and depression. Decreasing mental health may prompt more people to relive the happier of their pandemic memories.

“The pandemic makes me feel happy and sad at the same time, because I missed school for a year, and some of my older friends, for example, missed the Yosemite trip in eighth grade,” sophomore Amishi Arya said.

Like other forms of nostalgia, pandemic nostalgia is a subjective emotion. The emotions and memories later transformed into nostalgia for some can hold negative connotations for others. Being unable to talk face-to-face with friends, the constant fear of sickness and grief of family passings are all from a period that most would not wish to return to. However, that doesn’t mean nostalgic habits of the pandemic need to stay in the past or remain associated with suffocating isolation. Slowing down despite a busy schedule or allocating time to lockdown-typical activities — crocheting, making coffee — are all ways to find peaceful times.

“We can’t go back to it, but finding a positive in a hard or shocking or traumatic time, it is a really beautiful human trait,” Stevens said.

This story was originally published on The Epic on April 29, 2024.