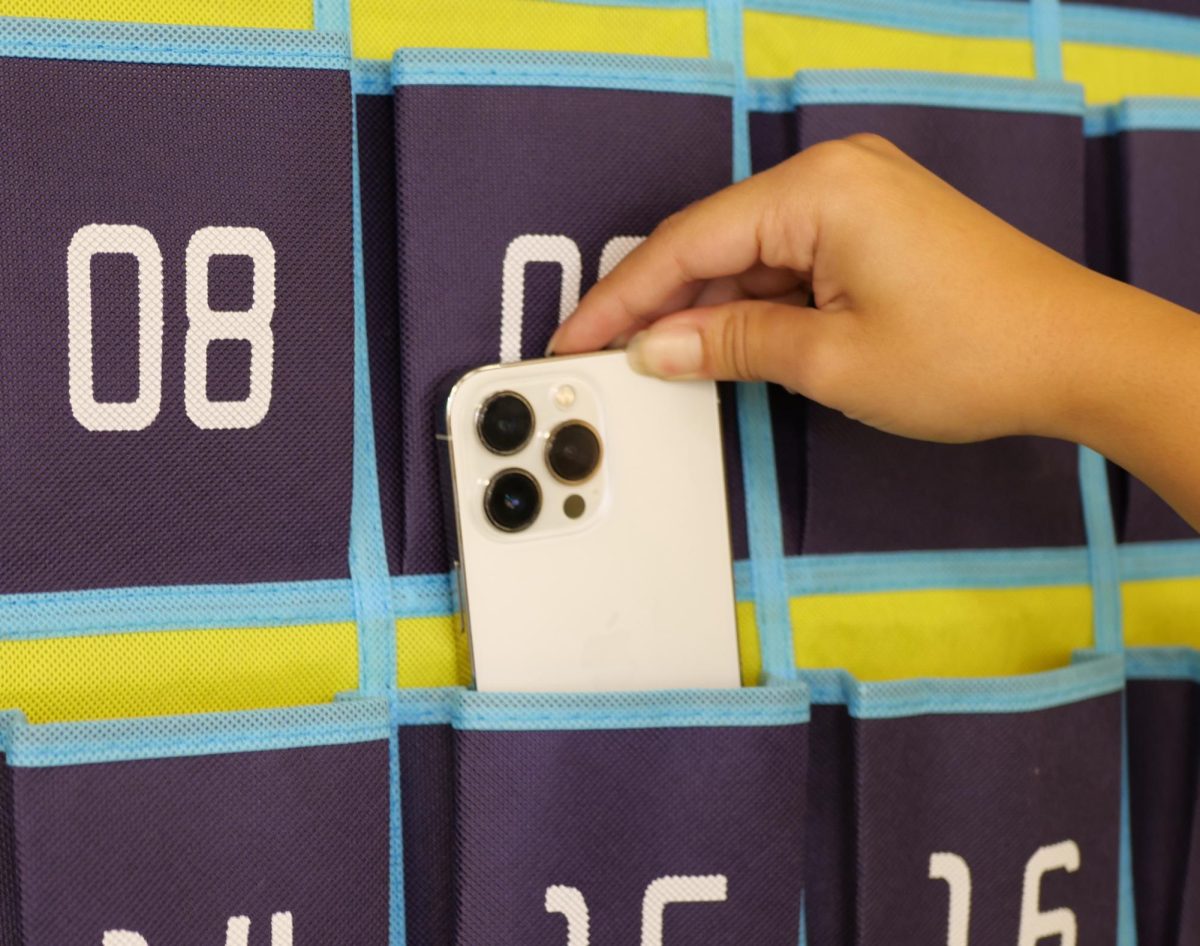

In one BOHS teacher’s classes, students slip their phones into hanging pockets on a wall as they walk through the door. When seated, students retrieve their pencils and books from their bags and focus on their teacher’s instructions, and the material before them.

Just a few classrooms away, student’s eyes frequently drift from their teacher to their phones, which sit face-up on their desks or on their laps. Some are scrolling through social media, some are listening to music with AirPods plugged into their ears, all more attentive to the screens on their devices than the screen projecting lessons to the class.

Elsewhere, a few students in a science classroom hide their phones under lab tables, and another student taps out a text while their worksheet lies blank on their desk.

In another classroom, students’ eyes are fixed on the teacher’s projected lesson slides, not a phone in sight. During breaks in the lecture, teens collaborate face-to-face, phones stowed in backpacks.

The reason for the great disparity in these learning environments: there is no uniform phone policy enforcement at Brea Olinda High School.

While BOHS’s policy this year is an improvement on last year’s barely-enforced plan, it still doesn’t go far enough to ensure that students stay focused in class without the temptation of their phones, and to ensure that teachers are supporting a phone-free learning environment.

The opportunity for learning — both the users of the phones and the students sitting around them — is sabotaged when devices are allowed.

The issue of student phone use on school campuses is severe enough that 13 states have passed laws restricting in-school phone usage, with California following suit with the passage of Assembly Bill 3216, also known as The Phone-Free School Act, on Aug. 28.

The law, which goes into effect July 1, 2026, will “require the governing body of a school district, a county office of education, or a charter school to…develop and adopt, and to update every five years, a policy to limit or prohibit the use by its pupils of smartphones while the pupils are at a school site or while the pupils are under the supervision and control of an employee or employees of that school district, county office of education, or charter school.”

Our current policy — the “No Phone Standard” — was introduced to the student body during Aug. 13-16 rules assemblies. The policy intends to curb student phone use by giving offending students a single verbal warning before their phone is confiscated and sent to the office by a campus supervisor.

It’s a sound policy, if enforced.

The problem, however, is that teachers do not uniformly honor the policy, creating disparate learning environments.

To combat this disparity, BOHS should join the other districts and high schools that have taken the lead in implementing phone bans and more uniform phone-use policies.

Los Altos High School in Hacienda Heights, for example, has adopted school-wide classroom phone caddies to hold student’s cell phones during each period.

At Rowland High School in Rowland Heights, “iPods, earbuds, and handheld gaming devices are not allowed at school” and phones are “deactivated and their use strictly prohibited” during the school day.

In the San Mateo-Foster City District in Northern California, magnetically sealed phone bags are utilized.

And in January 2025, a full year and a half ahead of the state-wide implementation of the Phone-Free School Act, Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), the second-largest school district in the nation, will implement a total phone ban at all schools.

BOHS should also take action and not wait until 2026 to improve campus learning environments and campus culture.

But it is not just the learning environment that is affected by phones. A study by the Pew Research Center revealed that “54% of U.S. teens say they spend too much time on their cellphones” and 36% of teenagers surveyed acknowledged that their phone use distracts them and causes anxiety.

BOHS administrators and counselors have made an obvious commitment to the mental health of their students — from the WellSpace Room in room 200 to this week’s lunchtime activities promoting suicide prevention awareness — but the devices that cause the most stress, anxiety, and depression continue to plague our campus.

We should not have some classrooms where students tune out lectures to check their Instagram feeds and some where phones are prohibited. Students need to be in an environment that encourages learning, direct communication, and focus — not one that allows students to use devices that adversely affect mental health and attention spans.

BOHS’s administration and the teachers who do not even enforce the existing policy should commit to adopting a stricter phone-free rule, to elevate student learning, to support our student body’s mental health, and to be proactive (because whether we like it or not, the Phone-Free School Act is coming in 2026).

For a phone-use policy to have any real benefit for students, a more robust, school culture-changing policy needs to be implemented.

Because while a phone ban may not entirely solve the mental health or attention-span issues many teenagers struggle with, a strong, enforced phone policy will be a giant step toward a healthier, and smarter, student body.

This story was originally published on The Wildcat on September 13, 2024.