HISD’s $4.4 billion bond package, the biggest bond in Texas history, is on the ballot this election period for Houston voters. The proposed package splits the bond into two propositions. Voters can check “FOR” or “AGAINST” on Propositions A and B during early voting today, Nov. 1, or on Election Day, Nov. 5.

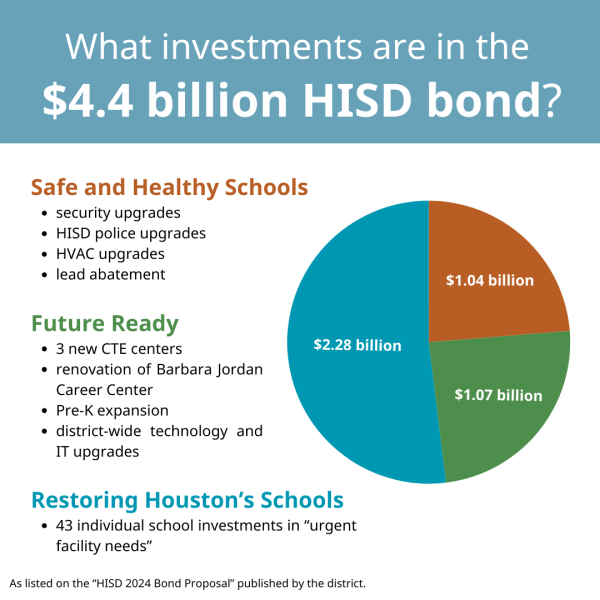

Proposition A focuses on infrastructure and requests $3.96 billion for items including “new school buildings” and the “renovation and expansion of existing school buildings.” Proposition B requests $440 million for technology equipment, systems, infrastructure and instruction.

While the district is required by state law to say “this proposition is a property tax increase” on the ballot, HISD explains on its website that it “conducted internal analysis and solicited multiple external studies” to determine that this bond would not increase the current tax rate.

The district’s Chief of Organizational Effectiveness Kari Feinberg highlights the bond as “an opportunity for us to invest in every single school that we have.”

“The investments are not necessarily all equal because we were really strategic in thinking about what our schools need,” Feinberg said. “We also know that our needs in HISD, especially in terms of facilities, are greater than what we would be willing to propose in one single bond. We tried to prioritize investments around first, safe and healthy schools; second, ensuring that our schools and our students would be supported in being future ready, and third, renewing schools in HISD that currently have the greatest facilities needs.”

An itemized list of what each school would receive if the bond is approved can be found by searching “HISD 2024 Bond Proposal All Campuses.” Per the list, Bellaire would receive $140,000 toward “security upgrades.”

Bellaire assistant principal and security coordinator Al Lloyd defines security as “risk management.” While the exact improvements would be determined only if the bond passes, Lloyd anticipates that these upgrades would go toward items such as installing cameras with AI technology and securing the “safety envelope” of the school.

“[To assess security needs] you want to do a safety audit of what is actually working, and you want to look at what’s not working,” Lloyd said. “Then, you walk with your campus administrators, and you look for areas where we can implement some safety strategies. Once we get the green light for [the bond], then we’ll start designing what those improvements should be.”

Feinberg said $4.4 billion is “only a fraction” of HISD’s “true need,” which HISD reports to be more than $10 billion. And while most districts of this size receive bonds every four to five years, HISD hasn’t received a bond since the 2012 package that funded many high school improvements, including Bellaire’s reconstruction. Most elementary and middle schools have not received additional funds since the 2007 bond.

Despite this need, the Houston community is split on whether this bond should pass.

A Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research survey conducted in January and August found that over 75% of HISD residents would support a bond that does not increase taxes. However, in August Z to A Research, commissioned by Texas Federation of Teachers, found that only 39% of HISD residents would support a bond that does increase taxes and that 77% do not trust the state-appointed board to manage the district’s funds. The varying language of each survey likely impacted their results.

HISD parent Eileen Hairel, an education advocate and member of HISD’s District Advisory Committee and Community Advisory Committee, campus PTOs and Shared Decision-Making Committees, perceives the bond as “investing in our infrastructure in a way we haven’t done in over a decade.”

“I tend to think of it as like a house,” Hairel said. “If you have a house and you don’t do any major repairs or upgrades for a decade or more, little things become big things, and the state of your home is not going to be very good after 10 or 15 years of not doing that stuff. That’s effectively what we’ve done as a district. We have a lot of buildings that are just old and in terrible condition, and we’ve got to do something about it.”

Hairel cites the amount and quality of temporary buildings on campuses across the district as a reason for her support of the bond. Some of HISD’s 988 T-buildings date back to the 1970s, with schools like Bonham Elementary having as many as 52 on campus.

“Earlier this summer, I walked into a temporary building classroom, and it smelled like a litter box that hadn’t been changed in a very long time,” Hairel said. “There was standing water outside the T-buildings. They are physically rotting. They’re breeding fleas and mosquitoes. That particular classroom is a second grade classroom. Those kids are in there all day, every day, breathing that, and they’re expected to learn in that environment. It makes kids sick. That gives you respiratory illnesses. Those kids wind up missing [school] because they’re sick.”

Hairel said even schools with little to no T-buildings, like Lanier Middle School, which was built back in 1929, struggle from old facilities.

“Once you get past a certain point of useful life in a system, the only choice that you have is to rip it out and start again,” Hairel said. “But in an almost 100-year-old building, that’s an almost impossible task to do. You have to either rip it all the way down to the studs and start from the very bare bones of the building, or knock it down and start again. That’s the situation in many of our buildings.”

However, Houston organizations like Harris County Democrats, Harris County GOP and Texas Federation of Teachers are opposed to the bond. The primary reasons include issues with co-location, doubts regarding how the estimated financial need of each school was calculated and a general lack of trust in the school board and superintendent.

Like Hairel, Community Voices of Public Education co-founder Ruth Kravetz also compared HISD to a house in need of repair.

“Let’s pretend my house is HISD: my house needs a new roof, my house needs better wiring, the plumbing could be upgraded and our air conditioning doesn’t work great,” Kravetz said. “But what if I pick an unscrupulous contractor to come to my house and do the work? Is my house going to be better off after the fact than before? No, I’ll still have a bad roof, bad AC, bad electricity, but now I’ll [also be] out a whole lot of money. When the bond is constructed as poorly as it has been constructed, you have to say ‘No, not this bond.’”

According to HISD, co-location “allows school communities to remain separate and distinct even as they share a parcel or building” while the original campuses are rebuilt or renovated. This is in contrast to closures, which involves redistributing a school’s faculty, staff and students across different campuses. Eight campuses would be co-located with seven campuses one to two miles away if the bond were to pass, costing $580 million.

For admin of Supporters of HISD Magnets and Budget Accountability Tracy Lisewsky, co-location is just closure under a different name. Lisewsky’s frustration partially lies in feeling that the community has not been consulted about these planned co-locations.

“I find it morally wrong that communities aren’t having a say in this,” Lisewsky said. “Why would you not include them in that conversation? The families who are used to walking their kids to school are not happy about this.”

Kravetz and Lisewsky are also concerned about money being funneled into schools that might close due to HISD’s declining enrollment.

However, while Hairel was initially “very skeptical” of co-location, after visiting campuses that were being co-located, she questioned what makes up a school community and appreciated the difference between co-location and school closure

“Over the course of the summer, community meetings and being on several campuses, my personal thinking on the issue evolved,” Hairel said. “One of the key components of that for me was, ‘Is a school community a building, or is it the people in the building?’ If you’re keeping your principal, your teachers, your friends, and [then] you’re [going] to a different facility, that is a different question. When a school campus closes traditionally, all of the students in that building get re-zoned to different campuses, not all to one campus. That destroys the community. Once I started thinking about a co-location that way, [it] helped me to clarify the challenge for HISD.”

Kravetz and the CVPE also cite how some repair and reconstruction costs for individual schools cited in the bond layout are $100 million more than what was found in a 2023 facilities assessment report.

“That’s not protection of our dollars,” Kravetz said. “As an organization, individual, mother, former teacher, former administrator, taxpayer, community member and Democrat, I support public education and I support public education bonds, but not this bond, not this time. Our kids deserve a better bond than this. Just because you want to improve our schools doesn’t mean you have to waste money.”

Despite being against the bond, Lisewsky acknowledges the need for renovation and rebuilding in HISD schools and hopes smaller bonds will be proposed in the future.

“There is no doubt that there are schools in HISD that need help, but this is the wrong bond at the wrong time,” said Lisewsky. “There will be 13 years that this bond is executed over, and there’s a lot that can change [in that time]. So we’re just like, ‘Just slow down. Let’s put out a bond for maybe a billion dollars that addresses immediate needs, and then let’s see where we’re going with population.’ With [HISD’s] declining enrollment [and] the lack of planning [and] fiscal responsibility, this bond is not well considered. In order to gain trust with the community, the superintendent should propose smaller bonds over a period of time.”

While the TEA takeover might not last the length of the bond’s implementation, Lisewsky and other opponents argue that the blueprints for how the bond will be implemented will be determined by TEA-appointed officials.

“[Miles’s] vision is going to be what goes into at least these first tranches of schools,” Lisewsky said. “So are these schools going to have libraries? Are they going to be built with team centers? Are they going to have rooms for musical instruction and theaters? It’s going to be his imprint that at least impacts the first round of schools.”

For Hairel, even if a new, smaller bond could be proposed as early as the spring, kids in HISD can’t wait any longer.

“A lot of students in our district have a lot of obstacles in their lives and come from environments that are challenging,” Hairel said. “School can be their clean, healthy, safe, warm, joyful environment, and right now, too many of them are going into an environment that isn’t any of those things. That’s something that we can control. We can control whether we fund infrastructure and fund maintenance, and we’ve got a lot of students that deserve a whole lot better than they’ve been getting.”

Feinberg encourages staff, students and families to take the time to learn about the bond proposal from “objective places and sources of information.”

“I would encourage them to have conversations with their principal about what the investment means for their particular school as well as schools that they may be considering going to as a middle schooler [or] high schooler,” Feinberg said. “I also would really encourage parents and students and faculty to take off their ‘school-specific hat’, and to think about what these investments could mean for all of the students and staff across HISD, in addition to what this just means for their individual school community.”

This story was originally published on Three Penny Press on November 1, 2024.