Statement from Principal Tracey Runeare:

Thank you to the Talon for giving me the opportunity to share with LAHS students how we address reports of harassment, discrimination, and sexual violence.

LAHS students deserve to attend high school in a culture of trust and safety. We take our duty to protect students from harassment and violence very seriously. We take preventative measures such as all staff participating in bullying, mandated reporting, and sexual harassment training, there is campus supervision and surveillance cameras on campus, and administrators monitor the campus during breaks and at student events. Students can report any incidents of discrimination, harassment, or sexual assault to LAHS administrators without fear of retaliation, judgment, or re-victimization. We investigate immediately and discreetly. We follow all laws, including Title IX and Education Codes, that protect students who report a complaint. If you are someone or know someone who has experienced or is experiencing any form of bullying, harassment or violence, please email or see an administrator, counselor, or therapist now so we can support you.

Student stories

In an attempt to bring awareness to the way our culture normalizes sexual harassment and assault, The Talon has compiled students’ stories about their experiences. Every source has chosen to remain anonymous, and their pseudonyms Lily, Lucy, Charlotte, Grace, Mia, and Jane, with the additional pseudonym of a third party, Ryan, have no connection to their identities. It takes enormous courage to be vulnerable in this way, so please respect their privacy.

Lily

*Some descriptions of Lily’s story were taken from a journal entry she shared with The Talon.

He leads her to the big bathroom stall in the 600s wing. It’s after school, so no one is around to hear them. He locks the door and begins undressing her. As she stands before him, completely bare, she knows she doesn’t want to go through with this. Even though they’ve been dating for 5 months, and even though they’re in love — or as in love as any 14 and 15 year old can be.

The gritty texture of the bathroom floor rubs her skin raw as he moves his body against hers; back and forth, back and forth.

The rhythm reminds her of the ocean. The day he took her to the beach, looked her in the eyes, and declared that he would marry her.

She is still imagining how the waves crashed into her legs when he bites hard into the cartilage on her ear. She wonders if he can feel her body trembling beneath his.

Then she is thinking of her mother. They have been fighting a lot recently. What would she say if she knew where she was?

“I love you,” he whispers in her ear after it’s over.

She remains silent. When he had asked her on a previous occasion, she said no. He knew she didn’t want to have sex in such a public space, he knew she asked him not to ejaculate inside of her. But he did it anyway.

“I just remember having had so many conversations about boundaries regarding PDA and sex,” Lily said. “I knew, if he hadn’t cared about it before, why would he stop if I brought it up again?”

“That’s why I didn’t scream or cry,” Lily said. “This was the person I thought I was safe around, and I loved him so much at the time that I had preferred to blame myself and stay comfortable in the pattern rather than realize that I was a victim.”

He gets dressed and poses her in the mirrors above the sinks before taking a picture of them to remember the moment.

“He knows, and I know — he raped me,” Lily said.

We don’t know if a court would have ruled this incident as rape and we don’t know what Lily’s accused perpetrator was thinking in the heat of the moment. We don’t know whether his intentions were true, or if he misinterpreted Lily’s silence as consent. Either way, Lily’s thoughts and feelings of the matter stay the same. The damage was done.

“When you’re raped in a relationship, you don’t feel like you were raped, you just feel like you were making your partner happy,” Lily said. “So, I had a really hard time coming to terms with the fact that I was violated.”

After that, Lily’s perception of love and relationships twisted around what she thought was expected of her — and all girls — mainly due to the abuse she suffered from her ex- boyfriend.

“I felt like if I wasn’t sexually appealing, I could never be loved by someone,” Lily said.

This incident in the bathroom wasn’t the first time, either. Lily was 12 years old when she first experienced sexual harassment. As a sixth grader, Lily started puberty before many other girls in her grade. That period of transition intended to be sacred was quickly tarnished as her developing body became a point of fixation for her classmates.

“Boys would tell me, ‘I think I’ve seen you somewhere like on that fun, orange and black website,’ talking about Pornhub,” Lily said. “‘If you ever need Plan B, hit me up, I can grab you a wire.’ I was not sexually active.”

At the time, most of these comments went over her head, but reflecting on them now, Lily remembers just how uncomfortable they made her feel.

Growing up having her body fetishized, Lily began to correlate her self-worth with the attention she received from it.

“For a long time, I felt like if I wasn’t pretty, I wouldn’t have value,” Lily said.

After breaking up with the boyfriend she said raped her in the bathroom, Lily began talking to a guy she thought was 16. It was only after they had sex that she found out he was 18.

California Penal Code Section 261.5 defines statutory rape as a legal adult of the age of 18 having sexual intercourse with a minor.

According to Lily, he had always known she was 15.

“These experiences have made me less confident of the person I am, and made me feel like I’m incapable of being pure, which I think is just such a stupid thing,” Lily said.

For a while, Lily didn’t tell anyone that she had been raped. Since she was dating her rapist and it occurred on campus, she thought she would be judged rather than supported.

“I didn’t tell people because I was really embarrassed that it happened on a school campus,” Lily said. “It made me feel like a whore.”

Slowly, she began to open up to her close friends and family.

She considered reporting her rapist, but doing so would mean reliving the experience in detail again — a price Lily felt would do more harm than good.

“I think about it probably every day,” Lily said. “I still question if it’s my fault or not. So I think reporting it would have just made it worse for me, in a way it would have taken all those feelings and exacerbated them.”

While Lily’s rapist no longer attends LAHS, she had to temporarily share the campus where she was raped with him. The accused crime occurred before the current administration was in place.

“It does not follow him around as I know it does me,” Lily wrote in her journal. “He does not fear when I pass him in the hallways. He does not flinch when I look him in the eyes.”

Lily’s life may forever be changed by the actions of hateful people, but she won’t let it define her.

Lucy

Lucy thought she shared mutual trust with her former partner, an LAHS student, until he pressured her past her physical boundaries.

She recounts particular circumstances where he would continually ask her to be intimate, and when she still said no, he would shame her for it. Eventually, Lucy let him do sexual things with her even when she didn’t want to.

“I didn’t want to be doing any of it,” Lucy said. “But I felt like if I didn’t do it, something bad would happen — that’s what he told me.”

According to Lucy, her ex-boyfriend coaxed her by saying everyone in relationships were sexually active, and that she couldn’t understand because boys were simply hornier.

After realizing how toxic their relationship was, Lucy broke up with her boyfriend. But those experiences stay with her.

“It gave me a lot of anxiety, which has seriously affected my mental health,” Lucy said. “It had never been worse after that.”

In particular, when she began opening up about what her ex-boyfriend had done, her friends were critical. Her ex-boyfriend’s friends were even worse.

“They said, ‘She’s just trying to get attention. She’s just trying to ruin his life. She’s a bitch,’” Lucy said.

Lucy felt used and betrayed. Her self-esteem reflected how she was defined by her decision to be or not be physical with her previous partner.

“It made me feel like I wasn’t a human, that I was just a body to be used,” Lucy said.

Although Lucy is not confident categorizing her experiences as sexual assault, what she knows for certain is that what her ex-boyfriend did was not okay.

“It’s not black or white; rape or not rape,” Lucy said. “You can feel so uncomfortable and something can ruin your self esteem. You don’t have to be trying to ruin someone else’s life by talking about it.”

Charlotte and Grace

Ryan and Charlotte began casually messaging back and forth after meeting in a class they had together. While innocent at first, the conversations quickly began to make Charlotte uncomfortable.

In person, Charlotte says Ryan once asked why her thighs were “so massive,” a moment that changed her perception of their interactions.

“I felt really uncomfortable,” Charlotte said. “I didn’t know what to do because I never really dealt with stuff like that before, so it was kind of awkward.”

Ryan would try to get a reaction out of Charlotte by doing certain things, which he admitted later over a text message, that he knew would make her upset. In one instance, he caused her to have a panic attack.

Charlotte describes these interactions as “harassment”. A friend who witnessed them tried to stand up for her.

That caused Ryan to confront Charlotte online, upset that her friend had interfered. In this conversation, Ryan made a comment which Charlotte interpreted as a threat of sexual assault. He later claimed it was a typo.

Ryan texted to say that her friend’s interference wouldn’t help, and that it only made him want to “fuck” her more.

Later, Ryan said he forgot to add “with,” a word that would change the meaning of his comment. F’ing with a person has an entirely different meaning than f’ing them. The next day, he offered a vague apology before Charlotte blocked him.

That same friend later reported Charlotte and Ryan’s interactions to a teacher, who then forwarded the concern to administration.

“I’m really glad it was reported because I knew it had to be done,” Charlotte said. “I was just scared.”

Charlotte was called in for a meeting with an administrator in which she believes she explained how Ryan was making her uncomfortable, implying his harassment.

However, according to Charlotte, the administrator facilitated a meeting between Ryan and her, a protocol not normally used in the situations Charlotte describes.

“If the situation was one where there was a clear bully or harasser and a clear victim, it would be unusual for us to put two students together.” Principal Tracey Runeare said.

In this joint meeting, according to Charlotte, Ryan explained his typo then claimed he had been the subject of rumors he wished to dispel. And so, after months of Ryan making her uncomfortable, Charlotte says she felt blamed when the administrator recommended she not show the screenshots to other students.

“The meeting ended with the administrator telling me to just not talk about it to anyone, which I found weird,” Charlotte said. “It felt kind of restricting, honestly. I feel like they could have done more.”

When asked, both the administrator who handled Charlotte’s report and Runeare said they could not share whether or why Charlotte was asked to meet with Ryan due to confidentiality concerns. However, Runeare wished to reiterate how the administration will always help students.

“We are grateful when students bring these kinds of concerns up to us because we don’t want this kind of behavior happening on our campus,” she said. “We take our role very seriously in creating a safe environment for our students, and a space for students to be able to talk to us about what is going on so we can help.”

Charlotte was offered support resources, and Ryan was asked not to interact with her on campus; the two have not talked since. Charlotte is not sure if Ryan faced any other consequences. However, Charlotte said she was brought in for another meeting recently.

Unknown to Charlotte at the time, she was not the only one Ryan had been harassing.

Similar to Charlotte, Grace met Ryan in a class they had together and began casually texting.

“It started off pretty normal,” Grace said. “We were talking about video games, grades, and specific teachers that we didn’t really like. It was pretty normal stuff that you talk about with friends.”

She didn’t think much of it until Ryan began making inappropriate and sexual comments towards her.

He would often send Grace a string of memes through direct messages. One video had text in the middle explaining how Ryan wished Grace was on top of him. A text he sent below claimed he was joking. Another time, he sent Charlotte a picture of a hole and said it reminded him of her.

In these circumstances, Grace would silence his notifications and ignore his attempts at conversation. She didn’t feel comfortable blocking him yet as she knew she would have to address it in person.

“I just thought that if I left it alone, he would just stop sending them and get the hint,” Grace said.

In class, Ryan was less direct, as Grace said being behind a screen seemed to give him the confidence to send obscene messages.

“He stopped himself and said, ‘Oh, I can’t say that because I’m in person, I can only do that online,’” Grace said.

Later, Grace wished she had the space to stand up to Ryan.

“When I realized how uncomfortable it made me feel, I started to get angry at myself for not realizing that I could have just shut that down,” Grace said.

Among the sexual comments, Ryan also sent messages that made Grace concerned for his well being and others. And so Grace reported him, but not for sexual harassment.

In fact, the way she thought sexual harassment reports were handled at LAHS, inaccurate to actual protocol, deterred her from reporting.

“I didn’t want to become a specific target,” Grace said. “[I think] when you report someone for sexual harassment they notify your parents and they notify the person and then you’re required to sit in the same room with them and talk about it.”

If Charlotte had kept silent about what she had experienced, she and Grace never would have met.

“I didn’t know until I started actually talking about him with other people,” Grace said. “I think that’s the most important thing: talking with others. I think there is some aspect of shame you’re going to have unless you talk about it.”

Mia

“I thought he was my friend,” Mia said. “I trusted him.”

Mia was hanging out with a group of friends after a party when one of her guy friends asked her to go on a walk with him. Thinking of it as nothing more than a friendly chat, Mia agreed.

However, when they left the group, he began making unwanted advances on her. When she turned him down, suggesting they return to their friends, he only became more persistent.

Suddenly he began kissing her, putting his hand in her pants and touching her vulva. When Mia realized what was happening, she immediately pushed him away and walked back to the group.

Mia was intoxicated, making her especially vulnerable, a situation she believes her guy friend took advantage of.

“Even if you’re intoxicated, you know not to do that to people,” Mia said.

Exports agree that if an intoxicated person cannot resist sexual advances, then they cannot give consent.

The next day, Mia confronted her assaulter who, according to Mia, told her to forget about it.

Once Mia realized what had happened to her, she began telling her friends. Some of them shared they had been in similar situations with him.

“I told people because I didn’t want it to happen again to somebody else,” Mia said.

Mia thought she could avoid him at school, but the next year, they were placed in the same class. Life on campus quickly became unbearable.

“I’d be so upset that I would usually go home,” Mia said. “I would skip classes, and I eventually had to tell my parents what was going on.”

Despite everything Mia had been through, she still believes the most painful part was the way in which other students reacted with shocking insensitivity.

“After a few months, the joking started because it wasn’t cool to hate him anymore,” Mia said.

When Mia requested a class change, Mia’s counselor reported the case to the administration, who notified the police.

Mia met with a detective, describing in detail what had happened to her. With what she felt was sincerity, the police said they would deliver justice. Mia has not heard from them since.

“They said, ‘We’ll get to the bottom of this,’ and then no emails, no texts, even though I gave them my email and my phone number,” Mia said.

When asked by The Talon last year what information was open to the public in investigations like Mia’s, the Los Altos Police Department (LAPD) referred to the California laws that protect the privacy of minors in criminal cases.

This year, The Talon reached out for an interview on several occasions, but was told everyone was busy and that it may take several weeks to schedule. It has been over a month since then, so it is hard to say why Mia was not notified after the initial report.

From her experiences, Mia wishes more students at LAHS knew this: “Take it seriously, because it is serious,” Mia said. “If you feed into someone’s behavior, they’re going to hurt more people, and they’re going to think that they can get away with anything.”

Mia’s assaulter no longer attends LAHS; however, Mia is uncertain whether it had anything to do with her report.

Jane

Three years ago, Jane began talking to her childhood friend who she had grown up with.

One afternoon, he came over to her house to watch a movie. Nobody was home to hear her when he began making sexual advances, and she said no.

Jane recounted how helpless she felt as he held her down and raped her until she stopped struggling, paralyzed with fear.

“After a certain point, I just kind of gave up,” Jane said. “I don’t remember everything. I don’t know if I just blacked it out or something.”

Jane went to the police to report the incident, but without any hard evidence, they told her it was unlikely he would be charged.

Jane didn’t tell anyone but her mom. Her response was first to ask what she was wearing — leggings and a sweatshirt — then to excuse his actions.

“She said that ‘he’s a man,” Jane said. “‘That’s just what they do.’”

Jane felt that her mom blamed her for letting him get that far because she was wearing what she thought was provocative clothing. And to a certain extent, she began to believe so as well.

“I felt like I could never find love or get married or do any of that because I wasn’t pure or virtuous,” Jane said.

Part of this feeling, Jane believes, comes from her family’s religious background.

“It’s also part of a religious aspect,” Jane said. “Sex has been so stigmatized to where it’s like, a guy can do it, and it’s cool; it’s fine in the eyes of the Lord. But if a woman does it she’s kind of ruined forever.”

While searching for an answer as to why she says she was raped, Jane developed an eating disorder.

“I needed to be able to control something because everything was out of my control,” Jane said. “And that was my outlet.”

Jane spent her freshman year trying to catch up with everyone. Each day was a struggle, even the little things she once found easy took more energy to do.

“It felt like I was walking up some giant hill,” Jane said. “I was running a marathon just to do what everyone else does.”

However, through time and lots of therapy, Jane finds that life has become easier.

“Every day hurts, but the more time that passes, it starts to hurt a little bit less,” Jane said.

These stories are more than isolated incidents. They are about real human beings, and they happen more than we realize. Jane is your neighbor. Lily is your classmate. Charlotte is your friend. Lucy is your daughter. Mia is your sister.

Definitions

In conversations about sexual harassment and assault, it is important to understand what each term means.

As the California Department of Justice defines them:

Sexual harassment: Unwelcome sexual advances, or other verbal, visual or physical conduct of a sexual nature that creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive environment.

Sexual assault: Unwanted touching of another person’s intimate parts, including sexual organs, anus, groin, buttocks, or breasts.

Rape: The penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the affirmative consent of the victim.

Statistics and Student Opinions

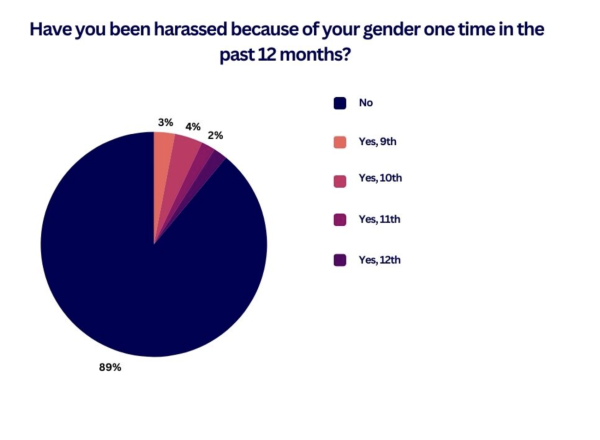

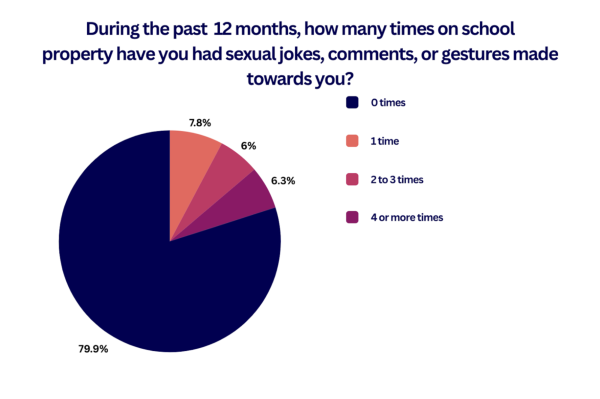

It is hard to gauge the number of people who have experienced sexual harassment or assault at LAHS. The closest formal measure of it was in the California Healthy Kids Survey students took last fall. According to the California Department of Education, the survey, which is anonymous and confidential, collects data about schools’ “climate, health risks and behaviors, and youth resiliency.” These were the results of the survey for questions about student’s safety and bullying.

11 percent of students reported that they had been harassed because of their gender, one time.

20.1 percent of students reported that other students had made sexual jokes, comments, or gestures towards them.

However, national statistics suggest the true number of students affected by sexual harassment and assault may be higher than reported in the survey.

From the National Sexual Violence Resource Center:

56 percent of teenage girls and 40 percent of teenage boys have experienced some kind of sexual harassment.

36 percent of girls and 24 percent of boys have experienced online sexual harassment.

1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime.

Some students believe that the prevalence of sexual harassment and assault on campus is due to a larger cultural stigma.

“People have always grown up thinking, ‘boys will be boys,’” junior Lucas Martin said. “The problems are definitely rooted way earlier than high school culture.”

“I don’t think it’s necessarily our school culture,” Lily said. “I think it’s culture in general.”

Students have noticed that often the way their classmates speak about each other, which they considered normal, is sexual harassment.

“He said he would hit it from the front, hit it from the back, eat it, and then keep it in the fridge for leftovers,” an anonymous student said.

“When girls are wearing shorts, we’ll hear boys talking about how she has a fat ass,” Jane said.

“[I overheard someone say] ‘Look at her tits hanging out from her shirt,” an anonymous student said. “It’s clear she’s begging to be fucked, what an open invitation.’”

“That joking culture, which I think is fine at certain levels, can be taken too far and then lead into conversational sexual harassment,” Grace said.

Part of the solution, students believe, is to hold each other accountable.

“There are people I know that are still friends with boys who have raped girls or assaulted girls, and I think that’s wrong,” Lily said. “I think people can change, but at some point, there’s a line you need to put down.”

LAHS policy and Title IX

Title IX, a law passed 52 years ago that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex, requires schools to approach sexual assault and harassment through prevention and protection.

The Mountain View Los Altos District (MVLA) updated its harassment and assault policies in 2022 to ensure that reports that fall under Title IX are handled accordingly. Additionally, posters were given to teachers to display in classrooms defining sexual harassment and listing the steps for students to report incidents.

According to Associate Superintendent of Educational Services and Title IX coordinator Teri Faught, the standard protocol taken when a student reports a case of sexual harassment or assault is as follows.

First, support services are offered to both the victim — referred to as the complainant — and the perpetrator — referred to as the respondent. Then, the families of both parties are notified.

Support services become more specific as the investigation goes on, and can include having a staff member assist in traveling from class to class, academic accommodations, and counseling.

If the student is reporting assault, the police are immediately notified, though their investigation and the school’s investigation are performed separately.

The investigation team, which includes Runeare and a few other administrators, then determines whether or not the report qualifies as a Title IX offense. For this to occur, the incident must take place during school hours on campus, be severe, persuasive, or offensive, and involve sexual assault, sexual violence, or stalking. If they believe the report may fall under one of these categories, they reach out to Faught, who does an intake with the complaint and their family to explain their rights under Title IX.

Complainants are offered the choice of a formal or informal route. The only difference is that the formal Title IX process includes more official communication and a written report that is shared with the complainant and their family at the end of the investigation. Besides that, informal investigations for Title IX offenses are performed the same.

Whether an offense falls under Title IX or not, every report is handled accordingly. An investigation involves gathering accurate, unbiased information, without judging either party. This may include talking to teachers, witnesses, conducting interviews with the complainant and respondent separately, and reviewing other evidence.

Depending on the severity of the incident, the respondent may be suspended, transferred, expelled, be forced to attend detentions, therapy or educational workshops, and monitored for several months after.

“It’s not just the punishment, but there’s this learning element that’s involved,” Faught said. “We can help that student understand why this wasn’t okay, and how this truly harmed the other person.”

However, this entire process depends on having a safe environment where students feel comfortable coming forward about their experiences, something Runeare hopes LAHS has already.

“We can really help when we have the information, and we know that that takes trust and time,” Runeare said.

“The more we speak out, the more that we stop these types of behaviors — whether they be physical or verbal — from reoccurring,” Faught said.

This story was originally published on The Talon on October 4, 2024.