The Mental Health America organization has proven that therapy can be a beneficial practice to patients’ mental health, and can give people who are struggling the resources they need to cope with what might be going on in their lives. A third party resource can give people a beneficial outlet as well as coping tools they can use to manage their struggles in the future.

The Human Relations Service (HRS) is a psychologist and psychiatrist-run non-profit therapy organization that offers its services to members of Wayland, Weston and Wellesley. They specialize in individual consultations, couples therapy, crisis intervention and community education about mental health topics.

“I’m a firm believer that everyone should connect with a therapist because you might need them at some point in your life and they can help and use different methods to support your mental health,” WHS wellness teacher Jennifer Reed said.

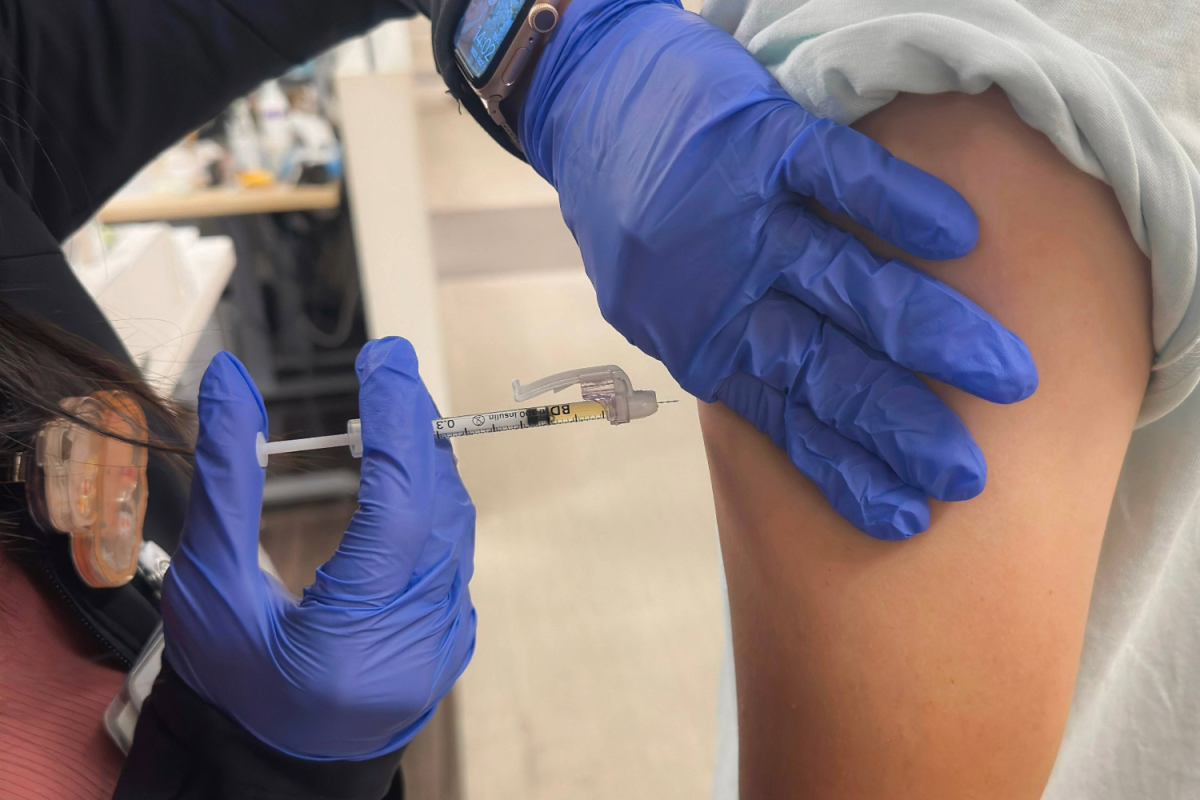

However, at the end of the day, not everyone can afford therapy. It can burn a hole in the wallet that some people are not able to compensate for. A recent Forbes Health study showed that the average cost of therapy in the United States is between $100-$200 per session, making weekly meetings between $5,200-$10,400 annually.

Whether a crisis has occurred in town, there’s a problem in the school system or an individual is struggling, it’s likely that not all members of our community will have the financial access to a coping method like therapy. Staff at the Human Relations Service located at 11 Chapel Place, in Wellesley, work to tear down this divide and make mental health treatment accessible to everyone in the community.

“The mission is simply to treat, reduce and prevent mental illness, and be a resource to families and the community as a whole,” HRS Intake Team Director Laura Matlack said.

The HRS was founded in 1948 by the former Mass General Hospital Psychiatric Department Chief, Erich Lindemann, after treating victims from the Cocoanut Grove Nightclub fire of 1942.

The despair caused by this tragedy inspired Lindemann to create a center that would promote the mental health care of a community as a whole, instead of just a couple of its members. This was the foundation of the HRS, making it the first community mental health center in the nation.

Now, the staff members at the HRS strive under Lindemann’s dreams to make their services available to all members of the community. The HRS works to improve the mental quality of the community as a whole, participating in community outreach opportunities that bring the people in the towns they serve, Wayland, Wellesley and Weston, together.

One way they can do this is through consultations with schools in the area by helping administrators find the roots of problems they might be facing among the student body.

“In that consultation, often people will present cases or present a systemic problem they’re having and we provide an outside perspective and try to work together to reach a solution,” Matlack said.

The community education and problem solving efforts are crucial to the efficiency of mental health organizations because of the effect it has on stigma. Mental health is a topic that has been stereotyped throughout the years, having had negative associations revolving around the idea of weakness in the past. As a society, we’ve begun to evolve from this belief and the obstructive cloud around mental health issues has begun to disappear.

“I’ve been in this field for a long time, and I’m seeing that stigma continues to lessen as time goes on,” HRS Director of Development Donna Portesky said.

Education efforts like these are crucial to the evaporation of the stigma surrounding mental health. When people know that they are in a safe space that normalizes these issues, it makes it easier to ask for help.

“People are much more willing to step up and say, ‘I think I’d like to talk to someone,’” Portesky said. “We have a presence in the schools, and we’re sort of part of the community or a fixture in the community, so I think we’re really approachable.”

The HRS also provides support and debrief outlets after a crisis has hit a community. Typically, if there is an untimely death or emergency in one of the towns they service, members of the HRS are one of the first organizations to be called.

They have offered evening programs for parents, office hours for community members who might be affected and advice on how to process grief.

“We ask ourselves, ‘How can we support families?’” Portesky said. “As a mental health agency, we’re there as part of the community safety net to support in any way we can.”

This isn’t the only way the HRS works to include everyone in the community. In contrast to private practices, they use a sliding fee scale, meaning the staff can cater to the financial ability of their patients.

“We’re a nonprofit, and one of the things that I think is really different is that we have a sliding fee scale,” Matlack said. “We really try to make treatment accessible for everyone, regardless of their ability to pay.”

By calculating the average cost for patients in the area and dividing it by the organization’s annual income, the HRS was able to come up with a minimum cost. The HRS then makes the fee more accessible by offering a variety of different payment options based on patients’ employment and other financial circumstances. This way the price of mental healthcare can be negotiated and tailored to the needs of everyone in a community.

To compensate for their financial accessibility, the HRS relies on fundraising initiatives from the community. They have a comprehensive fundraising program that depends on individual gifts, public grants and donations from foundations and events.

“It’s so vital [to fundraise],” Portesky said. “Especially in a place like the HRS, where even though it does receive some funding from town contracts, and we do get reimbursements from clients, it doesn’t cover our costs.”

In previous years, the HRS has held a fundraising gala during spring, but it has not hosted one since the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, the organization is shifting towards fundraising in more niche corners of the community.

“We’re revisiting how we might move forward with maybe some smaller events targeting individual groups and dedicating it more towards specific interests,” Portesky said.

The HRS is made up of about 25 social workers, psychologists and psychiatrists who meet with individuals and require compensation, but with a non-profit organization, there are times where public grants don’t cover these costs. The HRS relies on donations to compensate their staff who are pouring their time and effort into their work.

“It takes a ton of time, and it’s, again, not reimbursed, but we’re not going to stop doing it,” Portesky said. “We just need to raise the money so that the people can be paid for this work.”

To support the HRS, members of Wayland, Weston and Wellesley can donate, as well as spread knowledge of the existence of the HRS to members of their community.

“It helps us when people know about us and they appreciate the special value we have,” Porteskty said. “It’s a very unique thing to have an agency like the HRS supporting three communities.”

This story was originally published on Wayland Student Press on November 14, 2024.