Alia Rhodes ’27 lays on her bed, scrolling through Instagram, liking post after post containing altered and airbrushed images. Despite knowing each post is perfectly curated to portray only the best version of these influencers, Rhodes can’t help but pick apart the differences between herself and the bodies on the screen.

According to a study done by The National Library of Medicine, there was a correlation between the time spent on social media and one’s body dissatisfaction, occasionally causing eating disorders. Participants who compared themselves with idealized images had a higher dissatisfaction rate with their body than those who did not.

“When someone posts a picture of their body and how pretty they are, I want to be like them,” Rhodes said.

Rhodes finds that while her life does not revolve around expectations set by social media, she still finds herself feeling pressured and negatively impacted by online beauty standards. In agreement, health education teacher Jill Lipman recognizes how one’s self esteem comes from personal comparisons to unrealistic expectations caused by over-edited images online.

“Everybody’s looking at these airbrushed images, and we’re constantly bombarded with what we’re supposed to be looking like, whether that’s slender or athletic or built,” Lipman said. “With these images everybody’s getting the sense ‘this is how I’m supposed to look too’ and causes sadness when we don’t look like the pictures on social media.”

Dissatisfaction stemming from social platforms can lead to feelings of inadequacy compared to the ideals constantly projected within the media. For Khush Srinivasan ’25, the fear of facing judgment played as a motivator in working towards self-improvement.

“I started going to the gym, started doing skincare routines, eating better, just looking better and conforming with the social standards because nobody wants to be called ugly,” Srinivasan said.

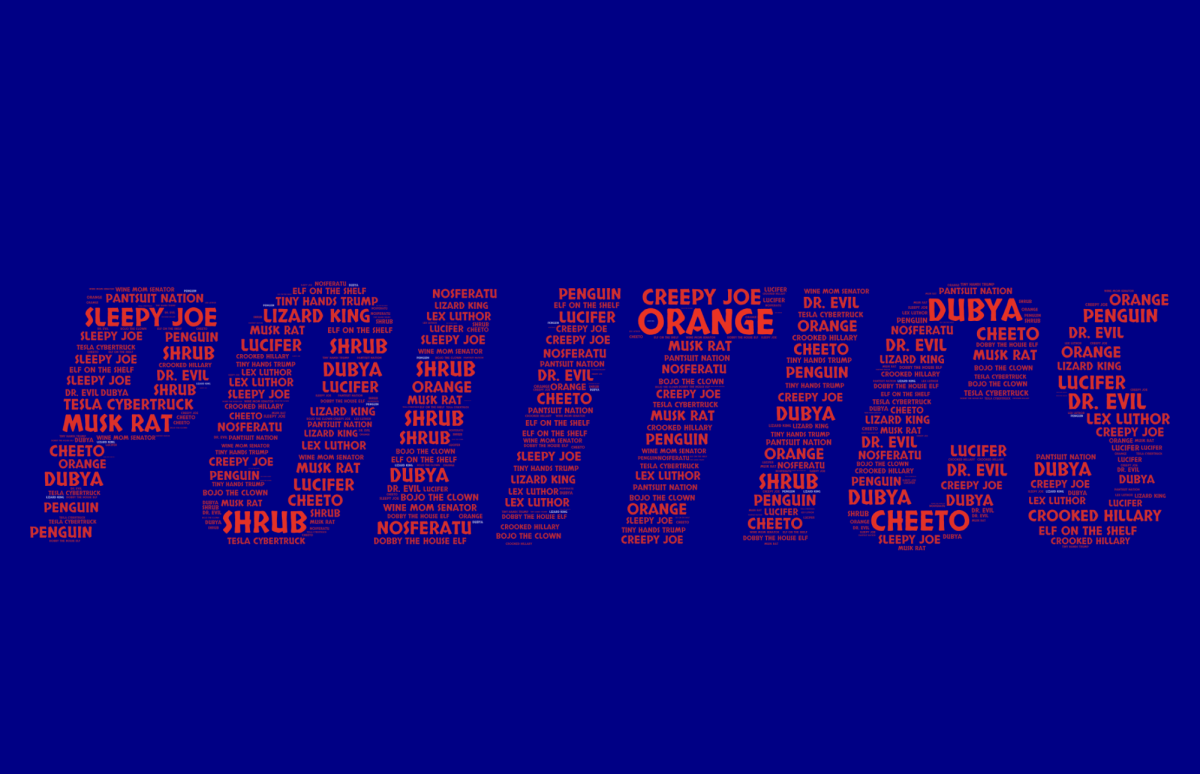

Psychology Today says “being attractive and rich makes one more likely to believe in a just world under the premise that one experiences less injustice.” Certain appearances are labeled as the standard and when meeting said standard, people face less criticism from others and are subconsciously treated better and are more accepted by society. For Srinivasan, societal standards of beauty are often pushed by algorithms built into platforms like TikTok and Instagram that seem to favor and give larger recognition to those who fit the ideal.

“The algorithm of social media pushes more attractive people out because they normally get more recognition,” Srinivasan said. “They’re probably fulfilling most beauty standards, and you see all that and think, that’s normal.”

Srinivasan points out the fact that social media presents the idea of being perfect as normal. Media platforms like TikTok tend to expose viewers to influencers, specifically those who curate their online presence based on physical appearances. Ella Wang ’26 believes that this singular beauty standard can harm anyone exposed to it, even those who fit within the standard.

“Anyone can have body dysmorphia, but when someone who’s skinny is dealing with body issues, they’ll post about it, and all the comments will just be negative saying that they’re fishing for compliments,” Wang said.

For Wang, the idealization of the perfect body standard can undermine the fact that anyone can face issues with body image and the perception that those who already meet the standard do so effortlessly. However, the effects of comparisons go beyond the website as Rhodes notices it overflow into real-life interaction with peers at school.

“I feel that it is comparative on social media, but then you see them in person and realize, this person isn’t just someone I have added on Snapchat or someone I follow on Instagram, they’re a real person who has all this beauty, and they’re my age, and I don’t do that,” Rhodes said. “Should I be doing that?”

The transition from social media ideals into reality can make teens further question their appearance as they compare themselves to their peers rather than influencers online, as mentioned by Christina Erickson, sponsor of Stevenson Styler Fashion Club. Students can get stuck in the endless mindset of there’s always something more that can be done.

“I would like to see students finding more normal, healthy relationships with food, diet, exercising, skincare, and all those things, as opposed to looking up to some internet celebrities,” Erickson said.

For Erickson, defining healthy goals that recognize the absurdity of lengthy workouts and unrealistic diets is crucial to finding a balance. However, it should be noted that the changes will not happen overnight and that larger brands can be seen to be taking a step in the right direction, implementing inclusivity of alternate images.

“There is diversity in culture and religions that you’re seeing of people in the fashion industry,” Erickson said. “People on the runway wearing a hijab or wearing different cultural identity garments, whereas you would have never seen that, 15 years ago.”

This story was originally published on Statesman on November 21, 2024.