It’s test day. Mahmud Jayanta* ’26 has been preparing for days, reviewing notes, retaking formatives, and watching AP Classroom videos. But for him, the real preparation begins the day of the test, asking students in earlier periods for the test questions, finding friends who took pictures or wrote down answers, and writing down notes in his calculator.

According to The International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI), 64 percent of high school students admit to cheating on tests and 58 percent admit to participating in plagiarism, with a total of 95 percent of students cheating in some form. The American Federation of Teachers also finds that cheating is more problematic in larger public schools such as Stevenson and in high achieving students.

“At Stevenson, it’s very easy to get test answers from other people,” Jayanta said. “It’s really hard for teachers to prevent cheating outside of class.”

Cheating the System

The Stevenson High School Student Handbook lists cheating as an offense of dishonesty and insubordinate and disrespectful behaviors. According to the American Federation of Teachers, many different behaviors fall under the category of cheating. They find the most common to be copying homework, getting test questions, and copying off another student’s answers.

“What I would call low-grade cheating is talking with others before a test, because it can even happen by accident and is so normalized,” Reyna Alam ’25 said. “More concrete high-grade cheating might include writing down test questions asked and distributing it.”

Alam draws a distinction between types of cheating based on intent but notes that both types of cheating are extremely present in many classes. English teacher Kirsten Voelker struggles with addressing cheating and supporting student needs.

“I know that if I have two-day in-class tests that the first night some people are going on AI and looking things up and trying to remember what they’ve been told,” Voelker said. “ But the two day tests are an effort to allow people to be more thoughtful and help students who struggle with timed essays.”

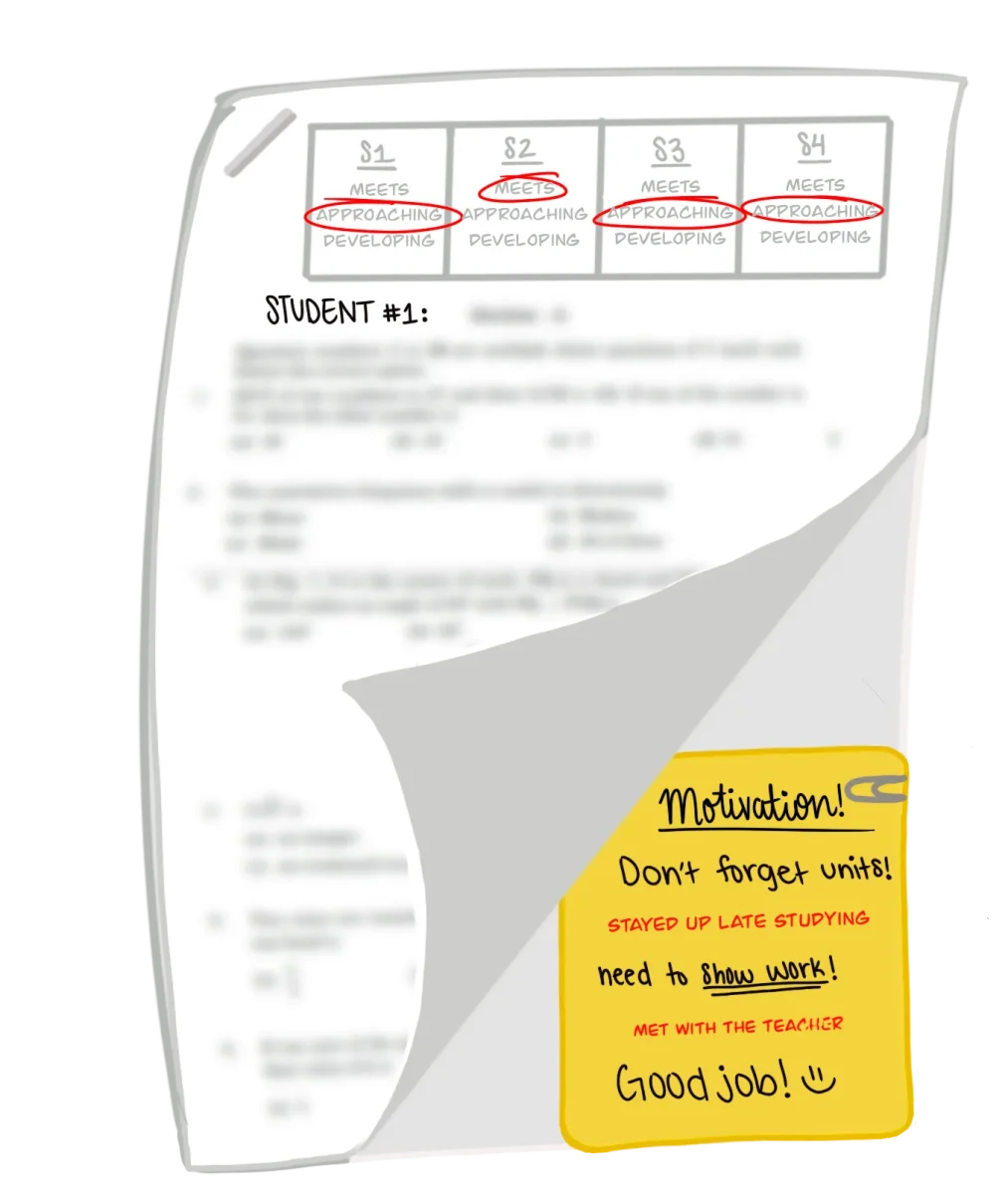

While teachers currently still see difficulties in combating cheating, Stevenson has implemented anti-cheating initiatives in the past. In 2014, Stevenson principal Troy Gobble piloted Evidence Based Grading (EBR), students are graded on four scores instead of earning a percent based grade on each test or “summative”: Developing, Approaching, Meeting, or Exceeding. Teachers ultimately take a look at the mode of “Meets” or “Exceeds” or if the student earned more meeting grades at the end of the year to show “growth”. Dr. Anthony R. Reibel, Stevenson’s Director of Research and Evaluation, says that cheating was one reason behind implementing EBR.

“With our grading model, we aimed to address some of the traditional grading issues, such as unfair point calculations, cheating, and test-related anxiety,” Reibel said. “We want smaller, more consistent assessments throughout the semester so that students could build both competence and confidence. And by the time they reach the larger unit assessment, students may be less tempted to cheat, because they’ve seen their own growth and feel more confident in their knowledge and skills.”

According to Reibel, the rationale behind the current grading system is to solve the main drivers behind cheating: stress and anxiety. Almost 50 percent of students in top high schools report feeling “a great deal of stress on a daily basis,” according to a study by New York University. Jayanta says that Stevenson, which is ranked the 6th best public high school in Illinois by Niche, falls under this category.

“The pressure of maintaining good grades throughout high school makes people determined, no matter what, to get all A’s,” Jayanta said. “You want to have 150 percent confidence in your grade, there’s no room for error.”

Toxic Environments

Jayanta feels that the academic environment at Stevenson creates a need to cheat more than other factors like student laziness. At the end of the day, Ryan Ren* ’26 believes these pressures originate from desperation.

“People that I know cheat pretty often on their tests because of the pressure a competitive high school like Stevenson puts on you,” Ren said. “A lot of people here shoot very high when it comes to their future and colleges, and then a lot of people feel pressure from their parents or their friends.”

Ren believes that the grind to succeed, and the cheating that comes with it, has become accepted. Alam sees this normalization forcing students to make tough, often morally dubious decisions. In particular, she notes that students can’t escape cheating.

“I feel like cheating is something that has always been there, at least among the some of the circles that I’ve been in,” Alam said. “But in order to distance yourself from the cheating, you’re putting yourself at a disadvantage, so there is this trade-off.”

Alam feels that one of the core reasons for widespread cheating is the need to fit in with peers who view it as normal. But Ren observes that when students see cheating become so prevalent, they feel like they are falling behind academically.

“And once the normalization happens, a lot of people end up seeing cheating as something that’s not even morally wrong,” Ren said. “I know people that are like, Oh, well, other people are doing this to get ahead, so why am I not justified in doing this as well?”

Shifting Policies

According to a study in the Journal of College and Character, punitive policies that focus on expulsions and suspensions shift accountability from an institutional level to a bureaucratic one. Reibel sees excessive punitive policies as unhelpful for students as well, failing to address the problems causing cheating.

“In our previous grading model, students could receive a zero on a test for cheating—a zero on a knowledge assessment for a behavioral choice,” Reibel said. “This one score, unrelated to their knowledge, could prevent them from earning an A in the class. At Stevenson High School, we value restorative practices. In our current model, students who cheat receive a Missing score and discuss their choices and consequences with their dean. We’ve moved away from punitive grading.”

While restorative practices are incentivized at Stevenson to allow for students to learn from their mistakes and reduce the amount of cheating in the future, some teachers disagree. Voelker believes that these restorative punishments don’t properly teach students who cheat that their actions are unacceptable.

“The idea that we’re supposed to give kids another try when they’ve cheated is ridiculous,” Voelker said. “If you cheat, you should be getting a developing. Your second chance is the next assessment in that skill area.”

Whether under restorative or punitive punishment methods, Reibel continues to see the use of unethical tactics to game the testing system. Throughout his role, Reibel has been working to prevent attempts to gain extra advantages by implementing the RegisterBlast sign-up system and timing buzzers.

“When I was asked to run the testing center, I noticed some students would take their make-up assessments during 8th period and linger into after-school hours to get unapproved extended time,” Reibel said. “With so many students signing up for 8th period, it created long lines of students waiting to test after school.”

Artificial Works

While traditional methods of cheating such as attempts for extra time are prevalent at Stevenson, new artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT have also created an alternative opportunity for academic dishonesty. But, Alam finds that just as AI can help students cheat the education system, it can also be used to support the learning process.

“I would say the most beneficial uses of AI that I’ve either used myself or just heard about is for notes or if you’re having trouble understanding concepts,” Alam said. “Asking for summaries of anything that’s your own personal notes is one example. I feel like AI is a great tool for that and I don’t consider that cheating.”

According to studies by the Stanford Graduate School of Education, even with the recent democratization of AI tools, cheating in high school has not gone up. Rather, the study finds that students who already cheat take advantage of new tools in unethical ways.

“I know a lot of people that write their essays with AI,” Ren said. “Some students just have an AI write everything out, and then they edit a few words. I think as AI becomes more developed it definitely needs to be something that’s addressed and restricted.”

Turnitin, a popular essay submission tool for 15,000 educational institutions and approximately 34 million students, detects both plagiarism and AI use. It found that out of 11 percent of assignments run through its AI detection tool across the globe, at least 20 percent of each assignment had evidence of AI use.

With the recent release of Chat GPT 5, Open AI’s popular artificial intelligence model has gained more advanced reasoning skills, context awareness, and multilingual support. As AI becomes more adept at producing test answers or essays for students, teachers at Stevenson are already comprehending the dangers of its use in the classroom.

“My thoughts right now are that AI has no place in an English class, especially if it’s giving students ideas,” Voelker said. “It’s a scary world if we continue to just rely on AI and people no longer know how to think and how to read something and distill information from it and not just be told it. That’s not a future I want to see.”

Voelker says cheating with AI could create a reliance on shortcuts that won’t prepare students for their futures in scenarios like secondary education or jobs. In contrast, Jayanta sees cheating as a necessary evil, with few red lines.

“I think it’s when you’re selling answers or a profit is when it’s too far,” Jayanta said. “If you want to take care of your buddies and you know they’re going to fail if you don’t do this then I think giving out answers is not as bad as selling them for a profit.”

Jayanta acknowledges that cheating is fundamentally problematic but draws the line somewhere he believes is more realistic: profiting from unethical behavior. Ultimately, Alam feels that solutions to this issue center around students.

“You don’t owe your friends by helping them cheat and that’s not something that you should need to do for people in your close circle,” Alam said.

This story was originally published on Statesman on December 18, 2024.